Overview

- North Carolina is overrun with 7,352 swine and poultry factory farms that produce vast quantities of manure.

- Of these operations, 156 are in or just outside floodplains – but even more facilities are probably at a higher risk of flooding.

- As the climate emergency intensifies, flooding from severe storms is more likely to flood factory farms, threatening human health and the environment.

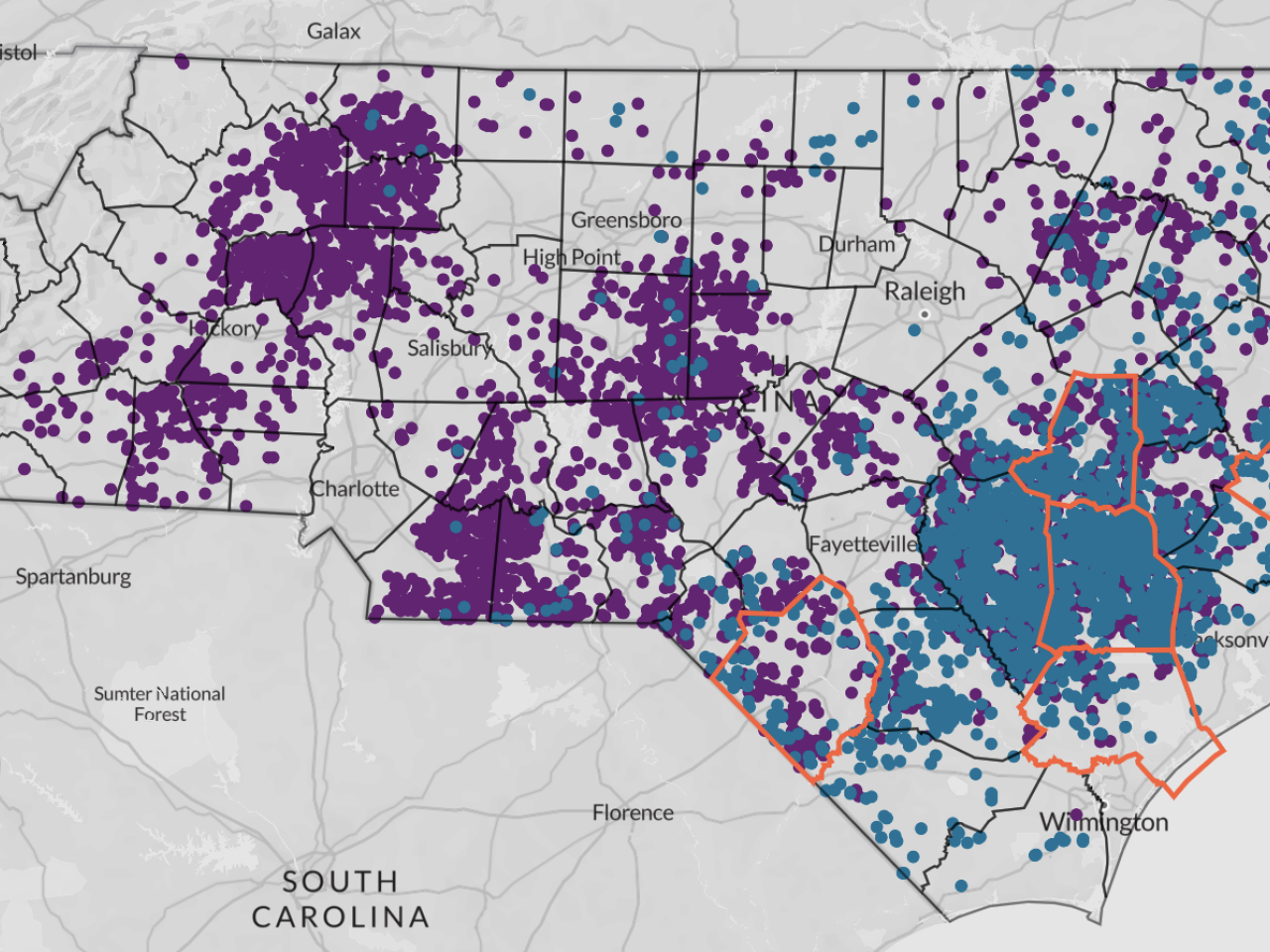

A new EWG geospatial analysis finds that, as of 2020, 156 of North Carolina’s swine and poultry factory farms are located in or just outside floodplains – 59 swine and 97 poultry facilities.

In total, we’ve identified 4,863 poultry facilities in the state that load about 544 million chickens and turkeys into huge, often windowless barns, and 2,489 swine operations cramming almost 8.8 million hogs into tight quarters.

These concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, generate extraordinary amounts of excrement and urine, which fouls waterways, sullies the air and sickens people – all with little state oversight or operator accountability.

The presence of so many of these CAFOs in or by floodplains poses significant threats to the environment and public health. That’s because flood operations are, by definition, especially prone to flooding during and after major rain events, which are becoming both more frequent and more severe as the climate crisis accelerates.

But floodplain science is woefully outdated. EWG believes that many more CAFOs in North Carolina outside the floodplain are at heightened danger of inundation, creating even greater risks over a much larger geographic area.

Figure. 1. Heat map of North Carolina CAFOs showing the concentration of swine and poultry CAFOs, from dark fuschia (least dense) to yellow (most dense), with the blue areas indicating the combined 100- and 500-year floodplain boundaries.

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

Outdated science underestimates risk of flooding to CAFOs

EWG found 71 CAFOs in North Carolina’s 100-year floodplain, 43 facilities in the 500-year floodplain, and 42 operations within a 100-foot buffer of the 100- or 500-year floodplain. (In some places, North Carolina has not designated a 500-year floodplain, making the 100-year floodplain boundary also the 500-year floodplain boundary.)

Mapping North Carolina’s floodplain CAFOs was a multi-step process. EWG researchers scoured aerial imagery from the Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Imagery Program to locate poultry CAFOs. We geolocated permitted swine CAFOs using data we got from the state Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ. EWG then overlaid all of these facilities with the state’s floodplain boundaries.

In North Carolina, floodplains are designated by the state’s Department of Public Safety working together with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. For most areas, there are 100-year floodplains and 500-year floodplains: the former supposedly have a 1 percent chance of flooding in a given year, versus a 0.2 percent chance of flooding each year in the latter. But many places across the U.S. in the 100-year floodplain and even the 500-year floodplain are now seeing flooding regularly.

Yet FEMA’s floodplain mapping process relies on old data that can miscalculate elevation and disregard small streams. It also uses previous events to predict future risk – a model that simply doesn’t work anymore, as the rapidly accelerating climate emergency changes all the odds.

Table 1. CAFOs in and just outside N.C. floodplains.

| Poultry CAFOs | Swine CAFOs | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-yr floodplain | 500-yr floodplain | 100-ft buffer* | 100-yr floodplain | 500-yr floodplain | 100-ft buffer* | |

| 37 | 33 | 27 | 34 | 10 | 15 | 156 |

*The 100-foot buffer extends from the edge of the 500-year floodplain boundary, where one exists, and where one doesn’t, from the 100-year floodplain.

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

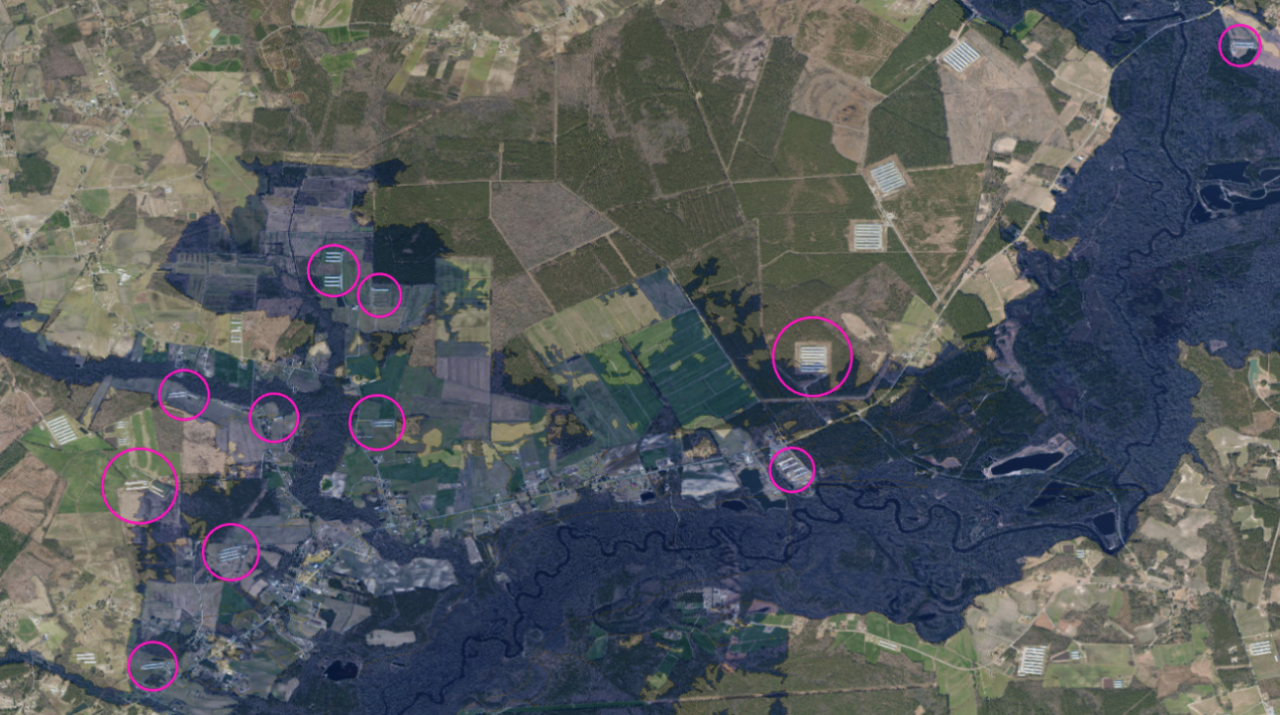

We found CAFOs whose properties were at least partially in a floodplain or were entirely surrounded by a floodplain, but not technically considered part of it because they were built on slightly elevated ground (Fig. 2). We also found swine CAFOs whose enormous cesspools or barns were built immediately adjacent to the 100-year floodplain boundary.

Figure. 2. A swine CAFO in Bertie County, N.C., surrounded by the 100-year floodplain.

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

According to the pork industry, since 1999, 43 swine CAFOs in floodplains have permanently closed after taking advantage of a state buyout program – but we found 59 still located in these higher-risk areas. And the program is chronically underfunded or not funded at all. There is no state buyout program for poultry facilities in floodplains.

It’s important to note that even CAFOs not located in floodplains can flood from heavy rain events, as demonstrated by a 2002 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill study of CAFOs in the eastern part of the state that were flooded one week after 1999’s Hurricane Floyd. The researchers compared satellite imagery of flooded areas to state-tracked reports of flooded operations, finding that only 20 out of 46 flooded operations were in areas that looked inundated in the photos.

The five North Carolina counties with the most floodplain operations are Duplin, Wayne, Pender, Craven and Robeson. Although they’re near each other in the southern part of the state, these counties are actually in three different watersheds – meaning they’re in danger of flooding from disparate waterways and their tributaries.

Robeson County is in the Lumber River Basin; Pender and Duplin counties are in the Cape Fear River Basin; and Wayne and Craven counties are in the Neuse River Basin.

Figure. 3. Some of the poultry and swine CAFOs in Duplin County, N.C., within or just outside the 100- and 500-year floodplains.

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

These counties may have the most factory farms in floodplains simply because they also are some of the counties with the highest number of total operations.

For example, we found 26 operations in Duplin County in or just outside floodplains. (See Fig. 3 for an example of one area of the county.) Duplin also has both the most poultry and the most swine operations of any county in the state: 1,064 facilities house nearly 52.3 million birds and over 2.2 million hogs (Table 2).

Table 2. The five North Carolina counties with the most total CAFOs.

| Top counties for CAFOs | Total CAFOs | Poultry | Swine | Cattle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duplin | 1,066 | 407 | 657 | 2 |

| Sampson | 931 | 375 | 555 | 1 |

| Wayne | 356 | 192 | 163 | 1 |

| Union | 298 | 295 | 3 | 0 |

| Randolph | 280 | 258 | 8 | 14 |

| Total | 2,931 | 1,527 | 1,386 | 18 |

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

Wayne County has the second highest number of operations in and just outside floodplains – 15 (Table 3). It also has the third most swine and poultry CAFOs, with 355 facilities housing almost 15.5 million birds and nearly 600,000 hogs.

Table 3. The North Carolina counties with the most CAFOs in floodplains

| Poultry | Swine | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In 100-yr floodplain | In 500-yr floodplain | In 100-ft buffer | In 100-yr floodplain | In 500-yr floodplain | In 100-ft buffer | ||

| Duplin | 10 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 26 |

| Wayne | 1 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Pender | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| Craven | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| Robeson | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

See all North Carolina counties here.

Source: EWG, from 2020 N.C. Department of Environmental Quality records, 2020 imagery from the USDA’s National Agriculture Imagery Program, and 2021 FEMA floodplain boundaries.

North Carolina’s manure problem (click to expand)

North Carolina’s factory farms generate almost unimaginable amounts of putrid waste. This manure is stored on site, typically open to the elements, before it’s applied, untreated, to nearby farm fields.

Typically, the waste doesn’t travel that far, because it’s expensive to move. One study found that the maximum distance that is economically feasible for farmers to ship manure is about 9 miles. Another study, of CAFOs in Ohio, found that swine manure is often sprayed within 2 miles of where it’s produced, while poultry manure may be applied up to 15 miles away.

On swine CAFOs, manure and urine are piped out as a thick, fetid liquid into open-air cesspools often euphemistically referred to as “manure lagoons,” which store millions of gallons of waste and whose dirt walls are prone to leaks, breaches and spills.

And on poultry CAFOs, chicken and turkey feces are shoveled, together with bird carcasses, feathers, and bedding, into enormous putrid piles euphemistically referred to in the industry as “litter” and often left uncovered and exposed to the elements.

By our calculations, every year North Carolina’s swine population produces nearly 9.3 billion gallons of liquified waste – enough to fill 14,076 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Poultry raised in the state generate more than 5.2 million tons of dry waste each year, about the same weight as 60,000 Boeing 737s.

Swine CAFOs above a certain size are required to apply for a waste management permit issued by the state. In theory, this requires them to commit to responsible handling of the enormous quantities of waste their animals produce, including reporting cesspool breaches or flooding events, not spraying waste onto fields right before a forecast storm hits or after a flood warning has been issued. But as EWG has reported, state oversight and enforcement is negligent at best.

Although annual inspections are ostensibly conducted on swine CAFOs, little more than a building permit is required to start a poultry CAFO. Almost none of North Carolina’s poultry operations have waste management permits – and that’s perfectly legal.

In fact, no state authority is tracking how much manure is generated by these facilities, or where and when it’s being applied. That means that no one has any idea whether the appropriate amount is being used at the right time in sustainable ways, or whether it’s regularly washing or blowing off into the nearest waterways.

Even when applied correctly, both kinds of animal fertilizer can pollute waterways.

Climate change is making flooding worse

No one really knows the extent to which CAFO animal waste already contaminates drinking water, especially in parts of the state with a shallow water table. But we do know that the risk multiplies with heavy rains and flooding.

Poultry feces are particularly susceptible to being washed into nearby waterways during rainy weather, especially in flood-prone areas. Legally, litter can be stored for up to 15 days in giant piles, but this is rarely enforced, with the advocacy group Waterkeeper Alliance repeatedly documenting brazen and consequence-free violations of this rule.

Bacteria counts and other water quality indicators near swine CAFOs are typically higher than other places, one study found – even more so after a rain event.

North Carolina is increasingly subject to more frequent and severe hurricanes caused by the climate emergency. Since 1999, eight hurricanes have hit North Carolina directly, frequently causing catastrophic flooding, including on CAFOs.

Other heavy rain events are also becoming more frequent and severe. In April 2017, a low-pressure system dumped up to 10 inches of rain in some parts of the state and caused sudden flooding that was some of the worst ever seen in those areas.

According to the North Carolina Flood Insurance program, every county in the state “has had at least two major flood disasters since 1950 – either from rising rivers or hurricane surge.”

When CAFOs flood, the enormous quantities of manure they produce and store on-site can wash into nearby creeks and rivers, carrying with it antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pathogens like E. coli and salmonella. This pollutes the environment and threatens drinking water and recreational water.

These effects can last for months after a major flooding event, as one study of post-Hurricane Matthew flooding in 2016 found. In North Carolina, at least 110 swine cesspools either spilled waste or came dangerously close. (Accurate numbers are impossible to find online. Within a few months of the storm, the state DEQ removed all such data from its website, and department representatives refused to provide accurate official numbers in response to a follow-up email inquiry pursued by EWG.)

Floods can also inundate barns, drowning chickens, turkeys and pigs, whose carcasses can then pollute waterways. The heavy rains brought by Hurricane Florence in September 2018, and the resulting weeks-long flooding, killed at least 5,500 pigs and 3.4 million chickens, according to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

A 2016 report produced by EWG and the Waterkeeper Alliance in the aftermath of Hurricane Matthew documented 26 poultry CAFOs with 102 barns overcome by flooding. One study of flooding from Hurricanes Matthew and Florence found that 91 swine CAFOs and 36 poultry CAFOs were overcome by flood waters.

CAFO manure threatens human health and the environment (click to expand)

Swine and poultry manure are loaded with chemicals like nitrogen, phosphorus and ammonia. When these chemicals pollute waterways used for drinking water, tap water systems have to use expensive treatments to clean it up. Nitrate contamination of water can contribute to higher risks of certain kinds of cancer and birth defects.

High levels of nutrients in waterways feed dangerous toxic algae blooms, which are exacerbated by the warmer weather and waters that scientists know are a prominent, probably permanent feature of the climate crisis.

Manure and the pathogens it carries – like Giardia, E. coli, salmonella, and Cryptosporidium – can taint private wells, causing severe gastrointestinal disease in humans. As many as 3.3 million North Carolina residents rely on private wells for their drinking water, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

According to one Duke University study, in North Carolina, “over 30 percent of CAFOs are located in areas where over 96 percent of residents drink well water.” Many wells are rarely, if ever, tested or treated for contaminants, making them especially vulnerable to contamination from factory farm runoff.

After Hurricane Florence soaked the state with up to 36 inches of rain over two days in September 2018, private wells saw big spikes in E. coli and other coliform levels, which are often used as an indicator for the presence of other pathogens.

CAFOs contribute to the dangerous and rapidly spreading antibiotic resistance crisis. Common ailments such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, C. difficile, UTIs, and STDs are becoming increasingly difficult to treat. More than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the U.S. each year, killing more than 35,000 people.

If that isn’t disturbing enough, experts at a 2004 conference at the University of Iowa School of Public Health raised concerns about siting swine and poultry CAFOs at the same location, and the specter of a global pandemic from new strains of bird flu incubated in swine and transmitted to people. The past three years made it all too clear how quickly a regional health problem can morph into a deadly worldwide pandemic.

Livestock facilities also emit air pollutants such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia and particulate matter that cause serious health problems like respiratory issues and infectious diseases in workers and neighbors.

Many of the state’s CAFOs are located in the eastern part of the state, in rural areas that skew more Black, Native American and Hispanic and have higher rates of poverty. These regions are also some of the most vulnerable in the state to flooding from big rain events, hurricanes and other severe consequences of climate change.

A 2017 EWG analysis estimated that 160,000 North Carolina residents live within a half-mile of a swine or poultry CAFO. But there is evidence that people can suffer dire health consequences even if they live several miles away from the nearest CAFO. In North Carolina, at least 960,000 people likely live within this zone.

More scrutiny of North Carolina CAFOs is needed

In 1997, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a moratorium on new swine operations that has kept the number of swine CAFOs fairly steady since.

But the state’s poultry industry has exploded from 147 million chickens and turkeys in 1997 to almost 544 million birds in 2020.

Because dry-litter poultry operations are almost completely unregulated by the state, they’re also exempt from public protections like odor ordinances and zoning rules.

The regulations that do exist and apply are woefully inadequate, or intentionally undermine any public accountability. In recent years, North Carolina’s General Assembly has passed evermore-stringent laws to limit court settlements or even prevent lawsuits against CAFOs – not coincidentally, as courts increasingly rule in favor of plaintiffs who seek some accountability for their suffering.

A 2014 state law makes it illegal for the state DEQ to consider third-party information to determine whether to cite a CAFO for an environmental violation. And the department may not publicly reveal these third-party complaints or any part of any resulting investigations unless it ends up issuing a notice of violation to the offending operation.

At the federal level, air quality near CAFOs is not monitored. And 50 years after the passage of the Clean Water Act, everything except the largest CAFOs remain largely exempt from federal water pollution regulations.

EWG recently joined a coalition, led by EarthJustice, of 51 citizens’ groups and environmental and community advocacy organizations petitioning the Environmental Protection Agency to improve its oversight of water pollution from CAFOs.