North Carolina lawmakers are rushing to pass legislation to fundamentally alter the legal rights of property owners, severely restricting the longstanding right to fair compensation for hundreds of thousands of residents whose air, water, health, quality of life and property values are threatened by the pollution and stench of animal waste from factory farms.

Despite bipartisan outcry that the measure is an unconstitutional attack on traditional property rights, House Bill 467 was fast-tracked through the state House of Representatives and approved April 10 by a vote of 68-47. It is now under consideration by the state Senate, where a nearly identical companion bill, SB 460, is in the Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources Committee.

The legislation would cap the amount of damages that could be sought in so-called nuisance suits brought by owners of property near concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs. Under the bill, people living near CAFOs or any other “agricultural or forestry operations” could only recover damages equal to an estimate of the reduction in the fair market value or fair market rental value of their property, barring compensation for illness, injury, damage to other physical property, or the inability to use and enjoy the property.

Swine operation within 600 feet of a residence in Onslow County, North Carolina.

Source: USDA The National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP), 2014

The state has provided no estimate of the number or location of residential property owners whose rights to relief from farm pollution would be sharply limited, or in many cases, effectively eliminated. Most property owners likely are unaware that the legislature is poised to curb or extinguish their rights to bring nuisance suits – a gross misnomer, given the serious impacts CAFOs can inflict on nearby residents.

But an EWG investigation has revealed the staggering scope and scale of the legislation’s attack on North Carolinians’ legal rights.

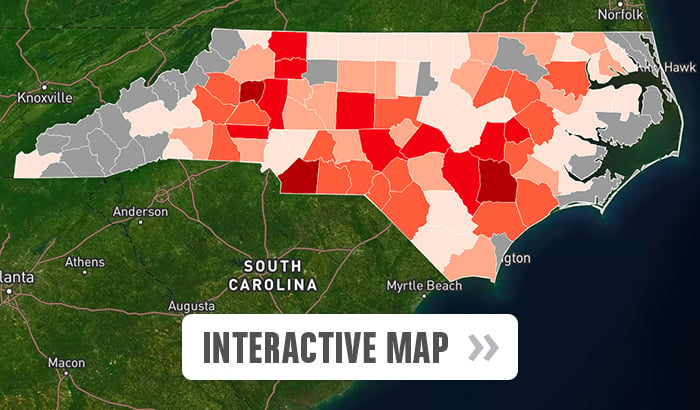

EWG conducted a detailed computer mapping analysis, drawing on geospatial data for the location of factory farms and digitized residential boundary maps from county tax assessors. We have created an interactive map that lets all North Carolinians see how close they live to CAFOs or the open-air pits that store liquid manure from millions of swine.

The analysis identified and mapped more than 60,000 presumed residential parcels statewide within one-half mile of CAFOs or manure pits. Based on U.S. Census figures for average household size in each of the state’s 100 counties, those residences house an estimated 160,000 North Carolinians. (See Methodology for how we determined a parcel was likely residential.)

But those numbers are only the tip of the iceberg for the legislation’s potential reach. Peer-reviewed scientific studies in North Carolina and other states have documented health problems, reduced air quality and noxious odors three miles or farther from CAFOs. Simple arithmetic suggests that 360,000 or more residences, and 960,000 or more residents, could fall within a three-mile nuisance zone.

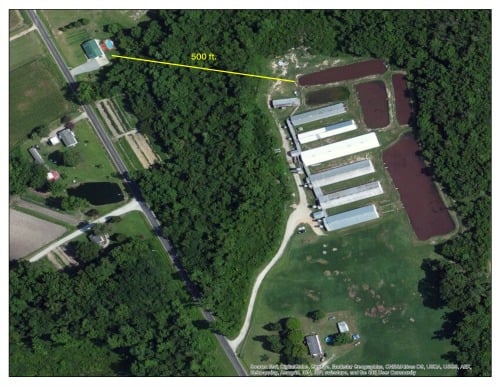

Swine operation within 500 feet of a residence in Lenoir County, North Carolina.

Source: USDA The National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP), 2014

The counties that would be most impacted are in eastern North Carolina, where the concentration of CAFOs is heaviest. In Duplin County, approximately 4,660 residences, housing an estimated 12,489 people – more than one-fifth of the county population – are within half a mile of a CAFO or manure pit. In Union County, approximately 4,255 residences, with an estimated 10,978 occupants, are within half a mile. A list of all counties, ranked by the number of residences and residents in the half-mile nuisance zone, is available here.

The bill applies to all agricultural and forestry operations, but clearly is most concerned with swine CAFOs. As originally written, HB 467 would have also applied retroactively to pending cases – notably 26 lawsuits against Murphy-Brown LLC, now the Hog Production Division of Smithfield Foods, the dominant player in the state's swine industry. An amendment to remove the bill's application to pending cases narrowly passed the House, but the provision remains in the Senate bill.

Smithfield, the largest pork producer in the world, is owned by WH Group Ltd. of China, formerly known as Shuanghui International Holdings. WH says it is a private company, but its purchase of Smithfield for $7.1 billion was financed by the Communist regime-controlled Bank of China, and an investigation by PBS Newshour and The Center for Public Integrity concluded that "the Chinese government does exercise management control."

The suits against Smithfield consolidate the cases of hundreds of North Carolina plaintiffs, whose complaints cite the multiple harms suffered by people who live near CAFOs:

The nuisance caused by Defendant’s swine has substantially impaired Plaintiffs’ use and enjoyment of their property, and has caused anger, embarrassment, discomfort, annoyance, inconvenience, decreased quality of life, deprivation of opportunity to continue to develop properties, injury to and diminished value of properties, physical and mental discomfort and reasonable fear of disease and adverse health effects.

But if the legislation passes, future plaintiffs would be unable to recover damages for most of those complaints. In many cases, property owners could only sue to recover the diminished monthly rental value of their property, and compensation would only cover a few years of diminished rental value. If the CAFO operator did not abate the problem, the nearby property owner would have to file another suit to seek more compensation.

Swine operation within 1,000 feet of a residence in Onslow County, North Carolina.

Source: USDA The National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP), 2014

During debate on HB 467 in the House Judiciary Committee, former Rep. Philip Lehman, D-Durham, estimated that in a typical case the diminished rental value might be $200 a month over three years, or a little over $7,000. For that modest amount, operators will weigh the cost of fixing the problem against simply continuing to pay the neighbor, so capping damages takes away the incentive for CAFOs to clean up their acts. Lehman is a retired lawyer who resigned last month from his temporary appointment to the House.

A former deputy state attorney general, Ryke Longest, told the Judiciary Committee that a principle of North Carolina law since the colonial era “has been that no property owner has a right to use their property in a way that harms their neighbor’s use of their property.”

Longest, who is now director of the Environmental Law and Policy Clinic at Duke Law School, went on to describe the real-life consequences the bill will have if it becomes law:

After you pass this law, no court can protect some landowners’ rights to have a picnic, or cook outside, or grow a garden. If your neighbor’s actions keep you from doing those things and the court finds the neighbor’s use is included in the overly broad category of agricultural or forestry operations, then you are out of luck. When courts can no longer protect your property rights, you no longer will have them. All the court can do is tell your neighbor to hand you a check. In effect, HB 467 is telling agricultural landowners that they have the right to condemn their neighbor’s property.

And in a letter to the Judiciary Committee, attorney Paul Stam, who served 15 years as a Republican state representative, said the bill – whether or not it applies to pending cases – is unconstitutional:

The basic rights of private property include the land, the air above it and the earth below. By reducing damages for protection of these private property rights, this bill raises serious concerns regarding whether, if passed into law, it would amount of an inverse condemnation of these property rights, not for a public use but for the private purposes of a corporation. No matter how well-intentioned, it is not constitutional.

Although people living within half a mile of a CAFO are most likely to suffer negative impacts, numerous studies document negative health effects at distances of up to three miles away. In 2014, Steve Wing and Jill Johnston of the University of North Carolina's school of public health reported:

Hydrogen sulfide concentrations within 1.5 miles of [hog CAFOs] in are associated with neighbors’ ratings of hog odor and inability to engage in routine daily activities, increased stress and anxiety, irritation of the eyes, nose and throat, respiratory symptoms and acute elevation of systolic blood pressure. A study of NC public middle school children who participated in an asthma survey, which was conducted by the NC Department of Health and Human Services, found that children attending schools within three miles of a [hog CAFO] had more asthma-related symptoms, more doctor-diagnosed asthma, and more asthma-related medical visits than students who attended schools further away. The same study reported a 23% higher prevalence of wheezing symptoms among children who attended schools where staff reported noticing livestock odor inside school buildings twice or more per month, compared to children who attended schools where no livestock odor was reported.[1]

The principal sponsor of HB 467 is Rep. Jimmy Dixon, a Republican who represents Duplin and Wayne counties, where an estimated 18,000 people live within half a mile of a CAFO or manure pit. Why would he push legislation that would strip one in 10 of his constituents of their property rights?

The Durham-based newspaper INDY Week reported that campaign finance records show that during his career, Dixon has received $115,000 from the pork industry, including more than $36,000 from donors associated with Murphy-Brown, now part of Smithfield Foods. The newspaper also found that every House member who voted for the bill received campaign contributions from "Big Pork," totaling more than $272,000.

For Big Pork, that's an investment that could save CAFO owners and operators many times that amount in damages they won't have to pay to people who live near factory farms. For North Carolinians, it's evidence that many of their elected officials care more about preserving Big Pork's profits than about protecting public health and property rights.

1 http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/UNC-Report.pdf. Citations for the studies referenced in this excerpt can be found in Wing and Johnston’s report.