Overview

- Crop insurance companies and agents received almost $33.3B from taxpayers and farmers over the last 10 years.

- Ten of these companies are owned by publicly traded corporations with enormous net worths and massive executive salaries.

- Lowering program delivery payments to companies and agents and other subsidies could save over $1 billion a year, while maintaining a safety net for farmers.

The federal Crop Insurance Program is known for paying billions of dollars every year to farmers when they experience reductions in crop yield or revenue. But the Department of Agriculture program also sends billions of dollars annually – much of it taxpayer-funded – to a small number of crop insurance companies that service the policies. Many of these companies are owned by extremely wealthy, publicly traded global corporations. The program also gives billions of dollars annually to crop insurance agents – a cost that has soared in recent years.

Just in the last 10 years, crop insurance agents and the 14 companies the USDA allows to sell and service crop insurance policies, called Approved Insurance Providers, received almost $33.3 billion from the federal Crop Insurance Program. A little less than half of this money was contributed entirely by taxpayers and was paid to companies for “administrative and operating costs.”

The remaining portion came from underwriting gains, or the amount of money leftover from taxpayer- and farmer-paid premiums when yearly losses are smaller than premiums. Although these gains are nominally not guaranteed, the government’s agreement with companies ensures a rate of return high above other insurance industries.

Ten of the 14 companies are owned by publicly traded corporations, seven of which are headquartered outside of the U.S., in places like Switzerland and Japan. These corporations are huge firms with large assets and astronomical CEO salaries, so taxpayers, and to a smaller extent farmers, are giving billions of dollars every year to wealthy corporations that do not need handouts.

Congress should reduce crop insurance company profits and payments to companies for administrative costs in the 2023 Farm Bill while still maintaining a safety net for farmers.

The Crop Insurance Program is designed to benefit private companies at taxpayer expense

The Crop Insurance Program has been heavily subsidized by taxpayers for decades. Some insurance indemnities come from the money farmers pay for their premiums, but much is funded by taxpayers. And taxpayers provide 62 percent of total premiums each year, on average.

The program is different from most other federal programs because of the “public–private partnership” that sends taxpayer money to companies. The companies then give some of the money to agents who do the actual selling of policies and insurance adjustments. Instead of the USDA solely running its own program, like it does with farm subsidy and federal conservation programs, the agency relies on private companies to service crop insurance policies.

Crop insurance companies and insurance agents receive administrative and operative payments every single year. These cover costs like adjusting crop insurance claims and selling and marketing the policies. Agents get administrative and operating payments based on a percentage of the premium of every policy that they sell, but the companies can also choose to give them additional money, within statutory boundaries.

The companies are only allowed to pay agents up to 80 percent of their administrative operating payments, so they also retain some of that money. Companies can give 100 percent of administrative and operating payments to agents if specific conditions are met – but only the companies know how often this happens.

Administrative and operating payments are always guaranteed – the companies and agents together get at least $1.02 billion a year, with a cap of $1.283 billion. But these payments have soared above the cap for many years because the cap only applies to some of the crop insurance policies sold by the agents. The companies and agents are able to get payments above the cap by selling certain policies that aren’t included in the cap.

The crop insurance companies also collect underwriting gains in any year where taxpayer- and farmer-paid premiums are larger than what the companies pay out to farmers when revenue or yield losses occur. Although underwriting gains are not guaranteed, the insurance companies almost always receive them. In the last 22 years, there were only two years where the companies did not have underwriting gains.

Agreements between the USDA and the crop insurance companies target the rate of return for crop insurance companies’ underwriting gains at 14.5 percent each year. This guarantees outrageous profits to insurance companies – and it’s much higher than the rate of return for other insurance industries. For example, the rate of return for the U.S. title insurance and property and casualty insurance industries has been under 10 percent in recent years.

Billions are at stake

The Crop Insurance Program is often lauded as a program designed to benefit farmers – but a lot of the money expended by the program actually pads the pockets of companies and agents.

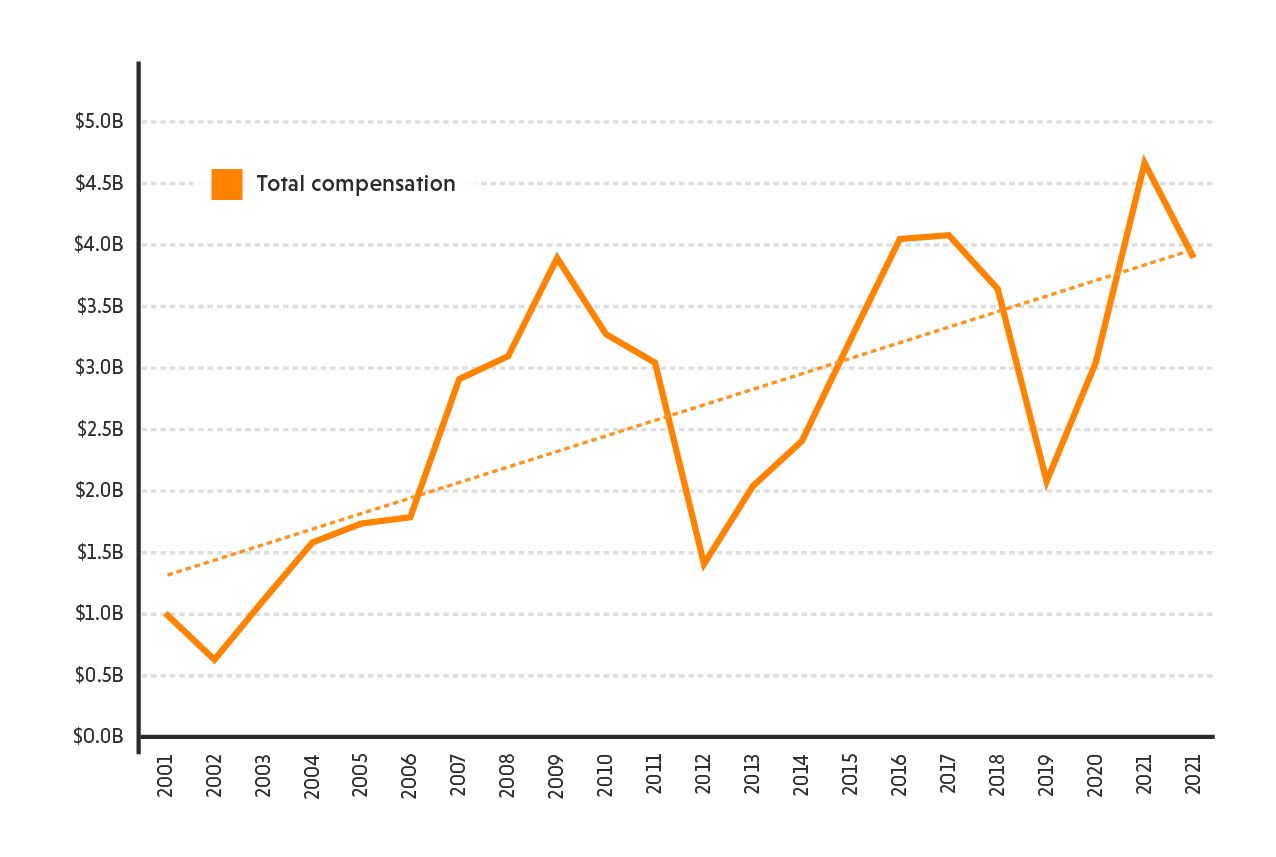

EWG analyzed data from the USDA’s Economic Research Service and Risk Management Agency, and the Congressional Budget Office to find the total compensation to crop insurance companies and agents over the last 22 years. We found it amounted to a shocking $58.8 billion between 2001 and 2022, with almost $33.3 billion of that paid out in the last 10 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual compensation to crop insurance companies and agents has gone up over time.

Source: EWG, from USDA Economic Research Service, Crop Insurance at a Glance, USDA Risk Management Agency, Crop Year Government Cost of Federal Crop Insurance Program, and Congressional Budget Office, Baseline Projections, USDA Farm Programs.

Just under half of the money – 47 percent – in the last 10 years was for administrative and operating payments, while 53 percent was for underwriting gains (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Just under half of the money between 2013 and 2022 was for administrative and operating costs.

Payments sent to companies and agents is a major portion of total spending of the Crop Insurance Program. Over the last 10 years, total payments to farmers through premium subsidies have fluctuated between $5.8 billion and $8.6 billion annually, while payments to companies and agents have totaled between $2 billion and $4.7 billion a year. In some years, up to one-third of crop insurance payments are made to companies and agents, not farmers.

Over the next 10 years, payments to crop insurance companies and agents are expected to be around $4 billion a year, according to the Congressional Budget Office (Table 1).

Table 1. Annual payments to crop insurance companies and agents are expected to be around $4 billion a year, 2023–2033.

|

Year |

Projected program delivery expenses (billions) |

Projected underwriting gains (billions) |

Projected total compensation (billions) |

|

2023 |

$2.12 |

$2.00 |

$4.11 |

|

2024 |

$2.15 |

$1.87 |

$4.02 |

|

2025 |

$1.89 |

$1.80 |

$3.69 |

|

2026 |

$1.90 |

$1.80 |

$3.70 |

|

2027 |

$1.90 |

$1.82 |

$3.72 |

|

2028 |

$1.91 |

$1.82 |

$3.73 |

|

2029 |

$1.92 |

$1.82 |

$3.74 |

|

2030 |

$1.93 |

$1.84 |

$3.76 |

|

2031 |

$1.93 |

$1.85 |

$3.79 |

|

2032 |

$1.94 |

$1.89 |

$3.83 |

|

2033 |

$2.21 |

$1.92 |

$4.14 |

|

Total 2023-2033 |

$21.80 |

$20.43 |

$42.23 |

Source: EWG, from Congressional Budget Office, Baseline Projections, USDA Farm Programs.

Many crop insurance companies are owned by wealthy megacorporations

Through the Crop Insurance Program, taxpayers – whose median household income was only $70,784 in 2021 – are sending billions of dollars every year to extremely wealthy global corporations.

There are now 14 crop insurance companies, compared to in 2015, when a previous EWG analysis found 17. The three missing entities did not go out of business; they were absorbed by other crop insurance companies.

Of the 14 crop insurance companies, 10 are owned by publicly traded companies. These are extremely wealthy corporations, each with a net worth of at least $1.5 billion and as high as $78.2 billion, as of June 2023.

The 10 public companies also had net incomes between $52.4 million and $9.4 billion in 2021. Annual compensation to each parent company’s CEO ranged from $660,150 to $24.8 million, and total annual CEO compensation across the 10 corporations was almost $112 million.

Seven of these parent companies are headquartered outside the U.S., in Australia, Canada, France, Japan and Switzerland (see interactive map).

EWG analyzed annual reports and proxy statements of the 10 publicly traded corporations to find this information.

Map of the 14 firms that sell federal Crop Insurance Program policies, along with information about their parent companies.

Of all 14 companies, only two are not owned by a parent company: Farmers Mutual Hail Insurance Company of Iowa and Church Mutual Insurance Company. One other crop insurance company, Country Mutual Insurance Company, is owned by a large private parent company, Country Financial. Because these companies are not publicly traded, we know little about them other than their names.

The other crop insurance provider, American Farm Bureau Insurance Services, Inc., is owned by the nonprofit organization the American Farm Bureau Federation, which lobbies for the subsidies that guarantee the profitability of crop insurance companies.

Reforms are needed to modernize the Crop Insurance Program

The federal Crop Insurance Program must be modernized to better serve farmers and to better prepare for the extreme weather caused by climate change. Guaranteeing outrageous profits to insurance companies through reinsurance agreements with the USDA does nothing to serve farmers.

Congress should reduce these nearly guaranteed crop insurance company profits in the 2023 Farm Bill, and can do so while still maintaining a robust crop insurance safety net for farmers.

Dropping from the existing 14.5 percent rate of return to 9.6 percent, as suggested by the Government Accountability Office, would save taxpayers billions of dollars. This rate of return is in line with – and still much larger than – that of many other private insurance industries. Studies show that these insurance companies would still participate in the program if their profits were “just” $1 billion a year.

Congress should also restructure how administrative and operating costs are determined to decrease the amount of taxpayer dollars flowing to companies and agents. Reducing subsidies to crop insurance agents to be consistent with historic norms could save almost $1 billion a year.

It makes sense to give crop insurance companies and agents a reasonable amount of money each year to sell and service policies, but $4 billion a year is well beyond the pale. These changes can be made to company and agent funding without hurting farmers, and can save taxpayers billions.

Bringing the profits of crop insurance companies and their parent corporations more in line with rates of return in the private insurance market, and reducing administrative and operating costs for companies and agents are good but small steps toward the far-reaching reform needed to reshape crop insurance into a safety net that works for farmers, taxpayers and the environment.