Overview

- Federal Crop Insurance Program costs have increased because of the climate emergency and are highly likely to grow as the crisis intensifies.

- The program discourages farmers from adapting to a changing climate.

- Reducing taxpayer premium subsidies in environmentally sensitive areas is a good first step to reform the program.

Farmers both contribute to the climate crisis – they’re responsible for producing at least 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions – and can also be devastated by its harmful effects, with extreme weather commonly destroying crop yields.

The Department of Agriculture sends billions of dollars to farmers every year from a multitude of farm subsidy, conservation and crop insurance programs. These programs need to be evaluated to gauge whether they encourage farmers to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change.

Those that do not, like the Crop Insurance Program, need to be adjusted. The federal Crop Insurance Program discourages farmers from adapting to climate change. This report recommends specific policies to reform the program so it better facilitates farmers’ adaptation to the climate crisis and costs taxpayers less.

The Mississippi River Critical Conservation Area, or MRCCA, is used as an example of why the program needs reform. The region is very important for American agriculture and has seen increasingly extreme weather because of the climate crisis.

Crop insurance premium subsidies have increased significantly in the MRCCA over the past two decades. Reforming crop insurance is imperative to reduce costs and to help farmers adapt to the climate emergency in a region with millions of acres of environmentally sensitive cropland.

Crop insurance premium subsidies are expensive in the MRCCA

The MRCCA consists of just over 1,000 counties in 13 states. Previous EWG research has shown that crop insurance payments to farmers in this region were over $50 billion between 2001 and 2020 and that almost $1.5 billion of those payouts went to farmers for flooding damage. Those funds instead could have paid farmers to permanently retire more than 330,000 flooded acres.

Mississippi River floodwaters have pushed into a cornfield near Yazoo City, Miss.

Photo: USDA

To get a payout from the Crop Insurance Program, farmers must first buy an insurance policy. They pay for part of the policy’s total premium – 40 percent, on average. Taxpayers pay for the rest, and that portion is called the premium subsidy.

When a farmer has a reduction in crop yield or revenue, they receive a payment from the total pool of premium money. The amount of the payment depends on the type of policy and level of coverage.

From 2001 through 2020, premium subsidies cost taxpayers almost $39.5 billion in the 1,022 MRCCA counties that received any subsidies. Of the 13 states in the MRCCA, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota got the most money in premium subsidies – over $22.9 billion. Counties in those four states alone made up 58 percent of total premium subsidies in the MRCCA.

Of the top 10 MRCCA counties with the most premium subsidies, nine were in South Dakota and one in Minnesota. The top 10 counties alone got $2.36 billion in subsidies (Table 1). They made up less than 1 percent of the total number of counties but received 6 percent of all MRCCA premium subsidies.

Table 1. The top 10 counties in the MRCCA received more than $2 billion in premium subsidies.

| County | State | Premium subsidies 2001-2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Brown | S.D. | $411,857,908 |

| Spink | S.D. | $341,038,169 |

| Beadle | S.D. | $236,503,639 |

| Edmunds | S.D. | $231,389,471 |

| Hand | S.D. | $228,898,997 |

| Sully | S.D. | $194,760,085 |

| Renville | Minn. | $189,733,732 |

| Hutchinson | S.D. | $183,695,422 |

| Faulk | S.D. | $177,187,487 |

| Clark | S.D. | $166,928,579 |

| Total | $2,361,993,490 |

Source: EWG, from the USDA’s Risk Management Agency, Summary of Business data files

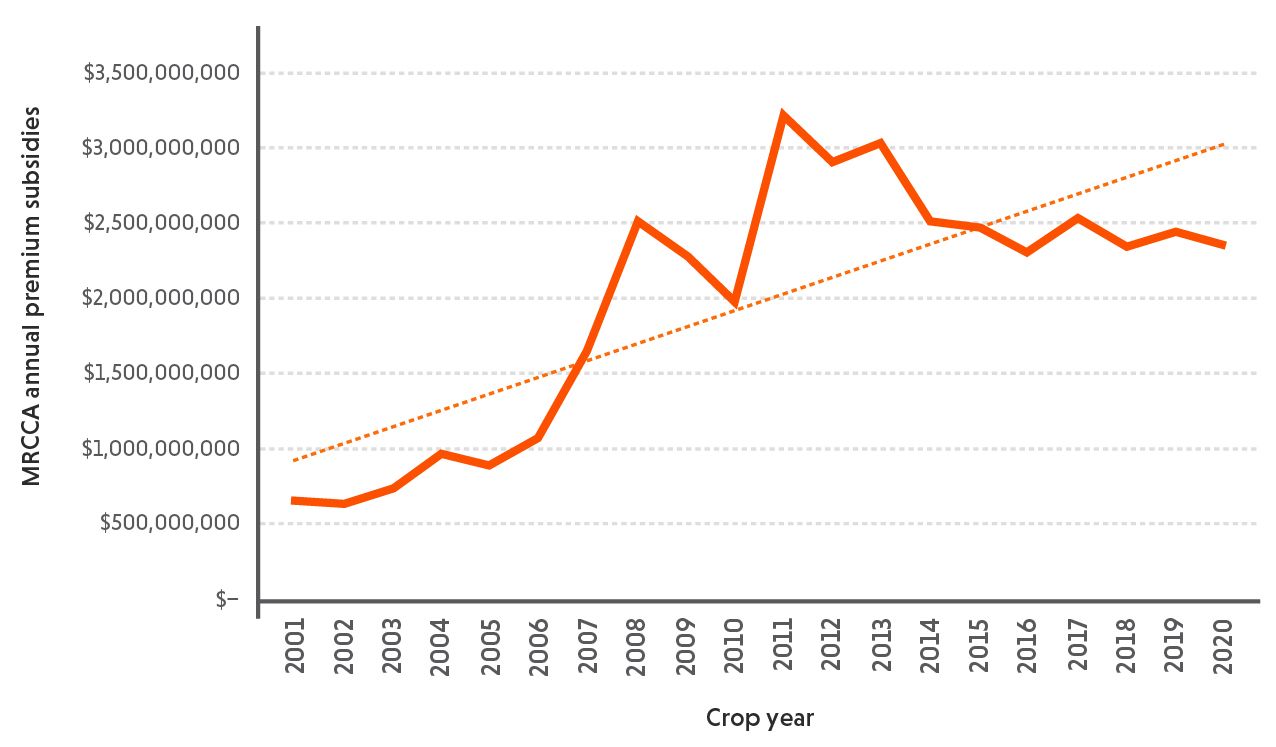

MRCCA premium subsidies have become more expensive. Total premium subsidies in the MRCCA showed a statistically significant increase between 2001 and 2020. Subsidies increased by 258 percent from 2001, when the region received just over $656.7 million, to $2.3 billion, in 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Premium subsidies in the MRCCA grew between 2001 and 2020.

Source: EWG, from the USDA’s Risk Management Agency, Summary of Business data files

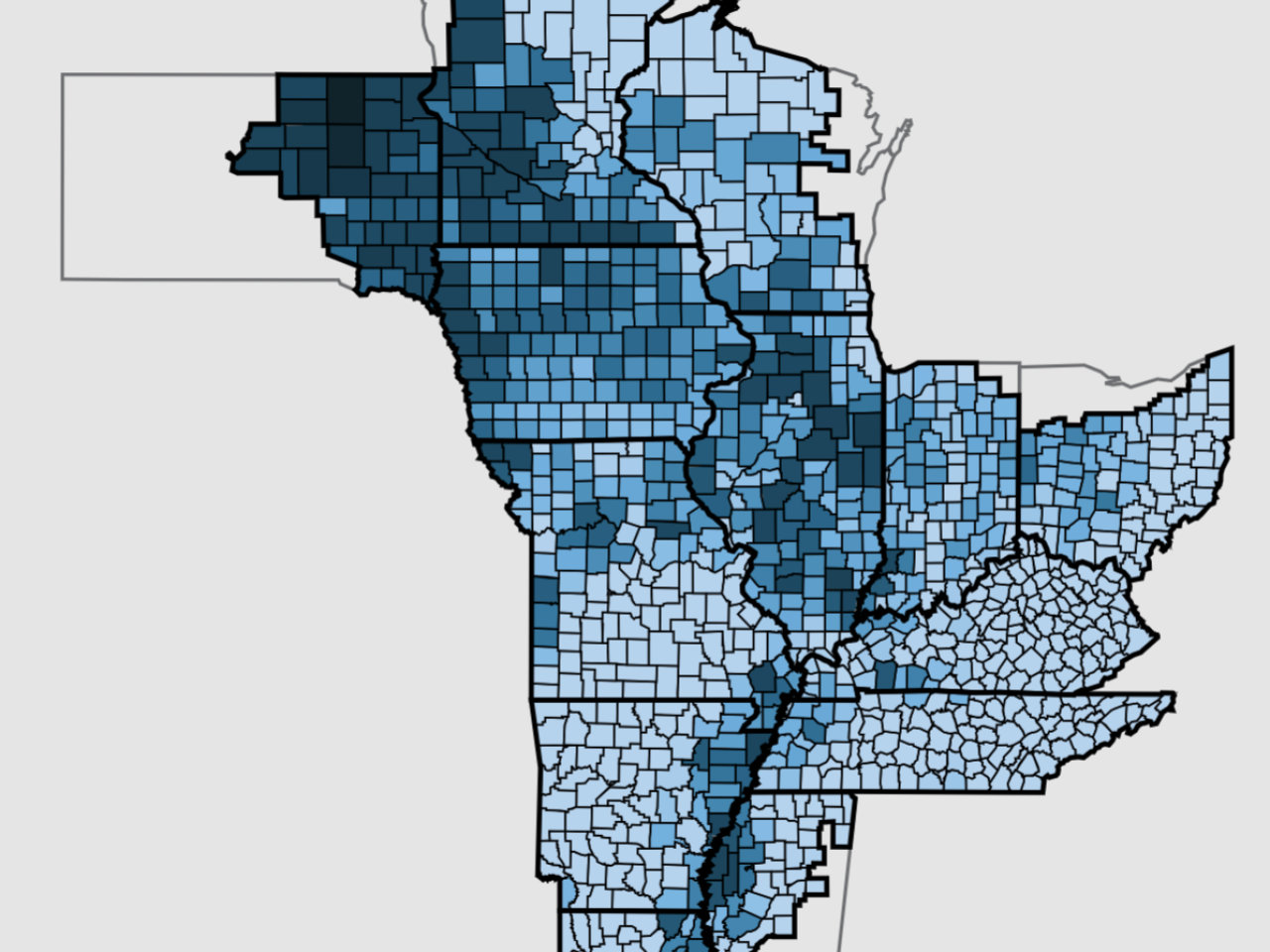

Premium subsidies increased across the MRCCA. Of the 1,022 counties that received a subsidy, 867 counties, or 85 percent, had a statistically significant increase in premium subsidies between 2001 and 2020. (See the Methodology section for more information.)

EWG’s interactive map shows county-level annual premium subsidies between 2001 and 2020. Each county pop-up box indicates the change in that county’s premium subsidies over time, including whether there has been a statistically significant increase.

The crop insurance program discourages adaptation to the climate crisis

Many factors influence premium and premium subsidy costs for specific crop insurance policies: a farm’s historical crop yields, number of acres insured on the policy, type of crop, crop price, level of coverage and risks of potential loss.

Because many of these factors vary with changing weather patterns, the cost of the federal Crop Insurance Program, including premium subsidies, is highly likely to increase in coming years. Experts predict that, in a scenario of 1 degree Celsius of warming, premium subsidies could increase by 22 percent, and, given 2 degrees of warming, by 57 percent.

More on-farm adaptation to climate change could lower farmers’ risks of crop yield and revenue losses and reduce the cost of crop insurance. But in many ways the Crop Insurance Program discourages farmers from adapting to the extreme weather conditions created by the climate crisis. Here are a few examples:

- Farmers are more likely to take risks when crop insurance pays for some of the costs of those risks. There is little incentive for a farmer to spend money on an adaptative practice when a crop loss is mostly covered by crop insurance.

- Since the program is so highly subsidized, farmers do not pay for the true cost of crop insurance policies. The subsidy itself may encourage farmers to take more risks, such as farming in areas that because of the climate crisis are no longer suitable. And since farmers do not pay the whole premium, they may not understand the full amount of risk they face each year and may also make riskier decisions.

- Insurance premiums in high-risk areas are often too cheap. The Government Accountability Office found that the differences between the premium target, which captures an accurate amount of risk, and the actual premium charged were largest in high-risk counties. Farmers are not paying enough for insurance in high-risk areas – those likely to struggle the most with extreme weather – so these farmers have an even less accurate sense of the amount of risk they bear.

- Insurance premiums are based on historical crop yields, and policies last only for one year. Even recent history does not reflect what weather conditions and their associated risks will look like in the future. Any program whose policies are based on the past and last for just a year is not one that is encouraging planning.

- Crop insurance increases the production of crops on marginal, environmentally sensitive land that is likely to be most harmed by climate change.

- The program encourages the growth of corn and soybeans while discouraging the growth of crops that would grow better in extreme weather conditions.

- Crop insurance discourages farmers from adopting conservation practices that could help them adapt to climate change. Farmers must adhere to “good farming practices” to qualify for crop insurance, so if they try conservation practices that help them adapt to or lessen the impact of climate change but are not considered “good farming practices,” they may not be able to qualify for crop insurance.

Mississippi farm field rows during the winter

Photo: USDA

Crop insurance reforms to reduce costs and facilitate climate adaptation

Reform of the crop insurance program can encourage farmers to adapt to the climate emergency and reduce program costs, including premium subsidy costs that taxpayers pay, in the MRCCA and nationally.

There are many reforms that could help both lower costs and encourage adaptation:

- Reduce premium subsidies for the highest-risk farmers to encourage less production in these environmentally sensitive areas. Put some of the savings into easement programs these farmers can use to permanently retire their cropland.

- Factor recent weather events like drought, as well as projected weather, climate and crop yield data, into the premium rating process, instead of simply using 20 years of a farmer’s historical yields, and extend policies so they cover more than just one year. These changes could help encourage farmers to plan for the long-term, instead of basing decisions on the past.

- Require local agricultural experts, like extension agents who define “good farming practices,” to include many conservation practices in their guidance on what meets that standard. Or the USDA could create its own list of good farming practices and include conservation practices with proven ways to adapt to climate impacts and lower emissions.

- Change the subsidy structure to encourage more farmers to use the Whole Farm Revenue Protection policy, which can help promote crop diversification – a potentially useful adaptation technique – and is less costly for taxpayers.

- Eliminate the Yield Exclusion provision, which allows farmers in particularly dry or wet areas to ignore bad years when insurance guarantees are calculated.

- Reduce crop insurance coverage levels for the Prevented Planting provision in the Prairie Pothole region, since it encourages farming in wetland areas that experience excess moisture in most years.

- As with farm subsidy programs, limit total amount of premium subsidies each recipient can get, and allow only farmers whose incomes fall below a certain threshold to qualify.

- Decrease premium subsidies for policies with the harvest price option, where insurance guarantees are based on the higher of the crop price either before planting or at harvest.

Reforms to federal Crop Insurance Program can help farmers adapt to climate crisis, cut taxpayer costs and facilitating nationwide adaptation to the climate crisis. But reforms would be especially important in the MRCCA, a region with millions of cropland acres that are especially vulnerable to climate change’s extreme weather.