Overview

- New EWG research finds fewer pesticides in baby food than in our groundbreaking 1995 study.

- Though we detected some pesticides, the most toxic have been removed.

- EWG’s advocacy helped drive market change – but the fight for safer food continues.

Your baby’s food may contain potentially harmful pesticides – but the Environmental Working Group’s decades of fighting to protect children’s health have helped eliminate the most toxic threats from these products.

That’s the conclusion of new EWG research, which detected nine pesticides in dozens of non-organic, or conventional, baby foods. The study comes almost 30 years after we issued a groundbreaking report, in 1995, investigating pesticides in the food that infants and very young children eat.

Babies and young children are particularly vulnerable to potential health harms from consuming food that contains residues of agricultural pesticides.

EWG’s newest research into popular baby foods found pesticides like acetamiprid, a neonicotinoid insecticide that studies increasingly suggest might harm humans as well as bees, and captan, which is linked to cancer.

The results are vital for parents and caregivers looking to limit the pesticides babies are exposed to every day. The study, along with EWG’s long-running guides to making safer choices when shopping, are designed to help consumers find baby food with few or no pesticides.

What you need to know from EWG’s latest tests:

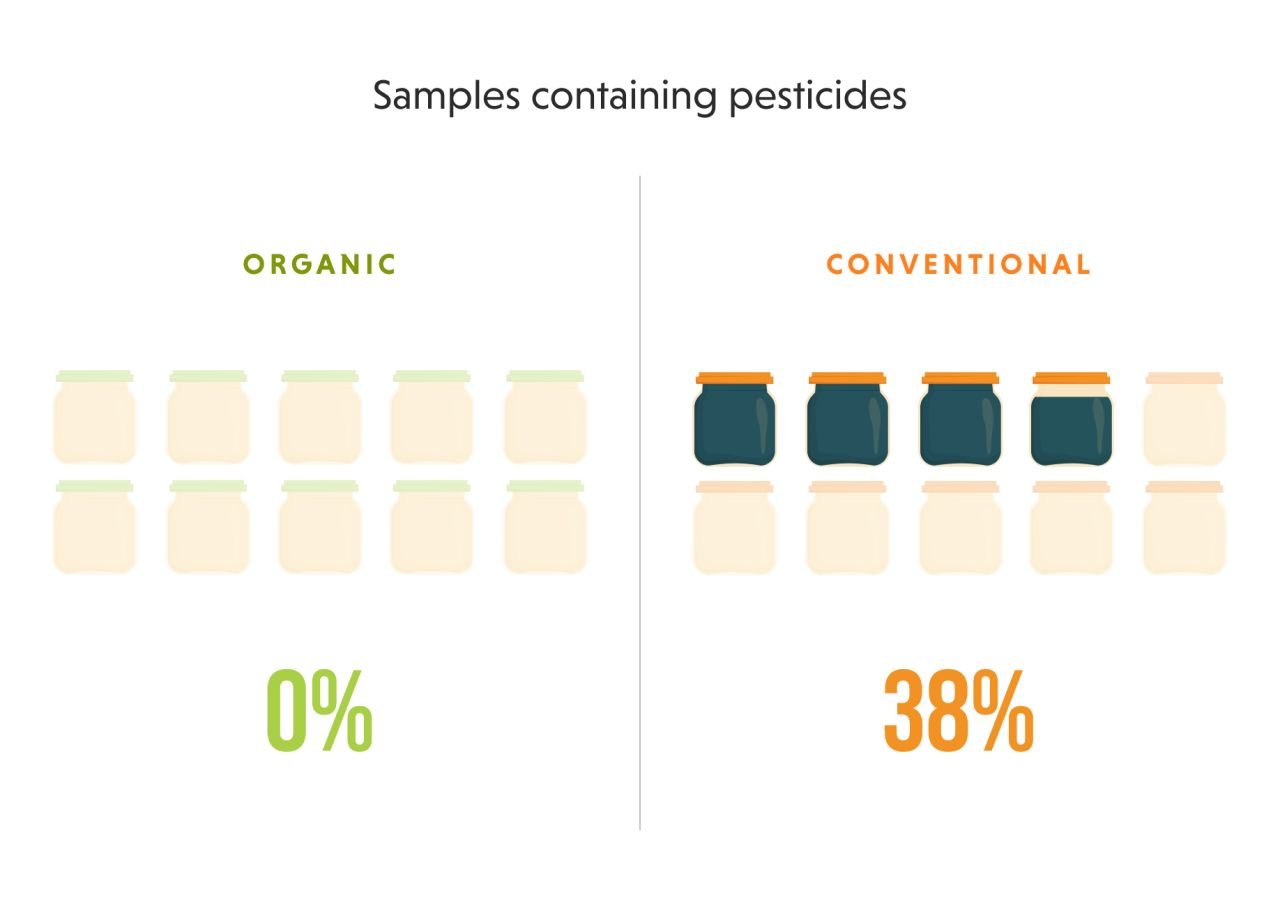

- We sampled 73 products – 58 conventional baby foods and 15 organic.

- The products were from three popular brands – Beech-Nut, Gerber and Parent’s Choice.

- At least one pesticide residue was detected in 22 of the 58 conventional baby foods.

- No pesticides were detected in any of the 15 organic products.

Any pesticides in baby food may be too much for children’s health. But parents should be relieved that some of the chemicals we found in our 1995 study are no longer being detected. That includes chlorpyrifos, linked to brain damage in children and the developing fetus, which we detected almost three decades ago.

EWG’s test results

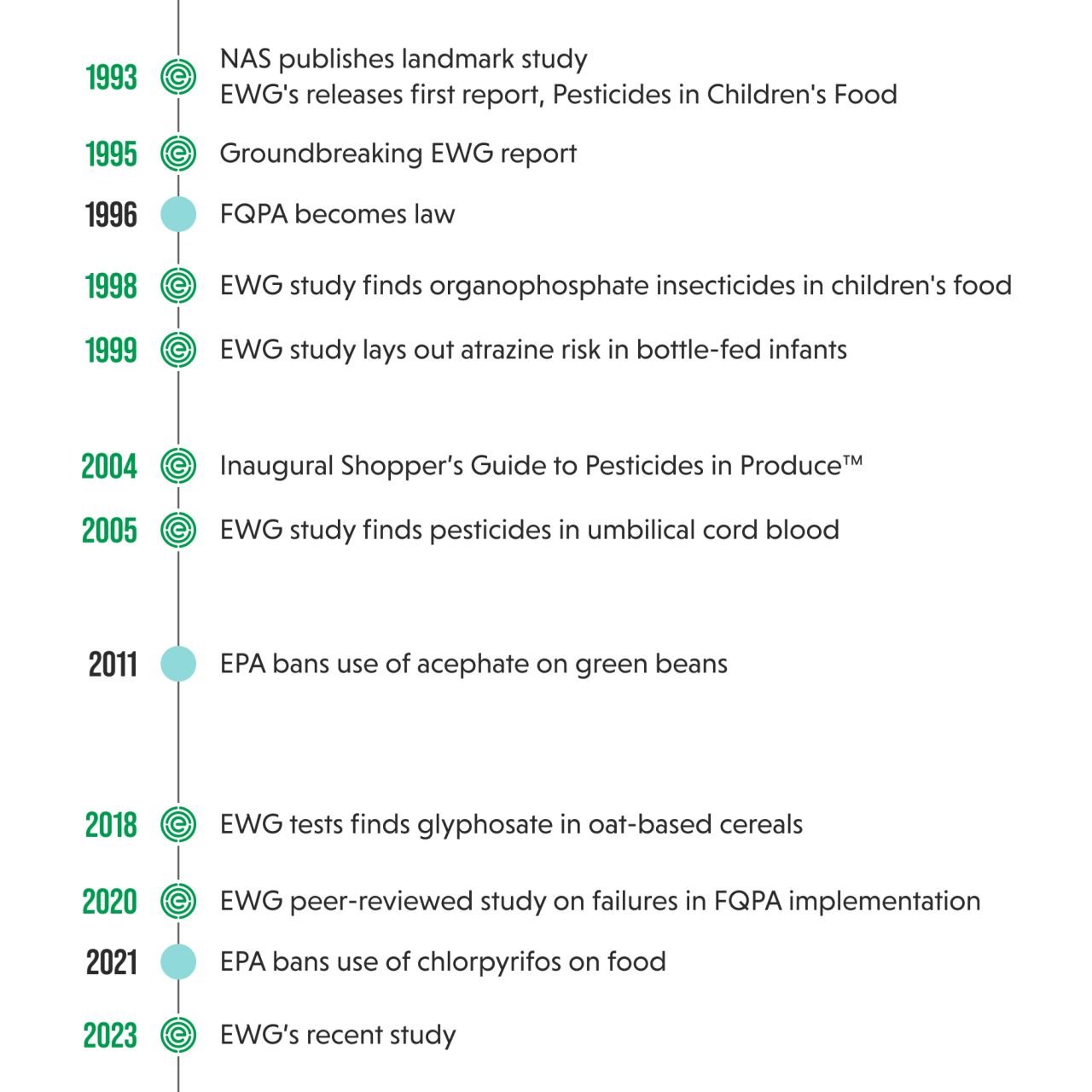

The threats pesticides pose to children’s health have been known since at least 1993, when the National Academies of Sciences, or NAS, published a landmark study warning of inadequate oversight of agricultural chemicals in the diets of infants and children.

Two years later, EWG released its first report on pesticides in baby food.

Almost 30 years later, we’re still finding harmful pesticides in baby food – although the chemicals are different now.

Which pesticides might be in popular brands of baby food?

Conventional baby foods are made with fruits and vegetables grown with farming practices that often include applying pesticides, including acetamiprid, captan and propiconazole, which may harm the reproductive system.

In contrast, organic-certified produce and products are held to much stricter standards. Organic guidelines do not allow the use of many toxic pesticides, which explains the absence of residues in organic products in our latest tests.

EWG’s 2023 tests detected nine pesticides:

1. Captan, and the captan breakdown product tetrahydrophthalimide, in 11 products.

Health risks: Likely human carcinogen, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

2. Acetamiprid in five products.

Health risks: May cause nervous system damage; reproductive toxicity suspected.

3. Fludioxonil in five products.

Health risks: May harm fetal development, cause changes in the cells of the immune system and disrupt hormones.

4. Pyrimethanil in four products.

Health risks: May harm the reproductive system.

5. Imidacloprid in three products.

Health risks: Harm to the nervous system of the developing fetus; harm to the immune system; harm to the reproductive system.

The other four pesticides detected were chlorantraniliprole and dodine, each in one product; methoxyfenozide in two products; and propiconazole in one product. There’s little data available about the potential toxicity of these agricultural products.

Which ingredients are linked to pesticides in baby food?

The presence of certain ingredients in baby food may indicate that the product is more likely than others to contain pesticide residue. Avoiding products made with these fruits or vegetables may help reduce pesticide exposure.

For example, EWG’s tests revealed that if one of the products in our study included non-organic apples as an ingredient, it was over five times more likely to contain detectable pesticide residues.

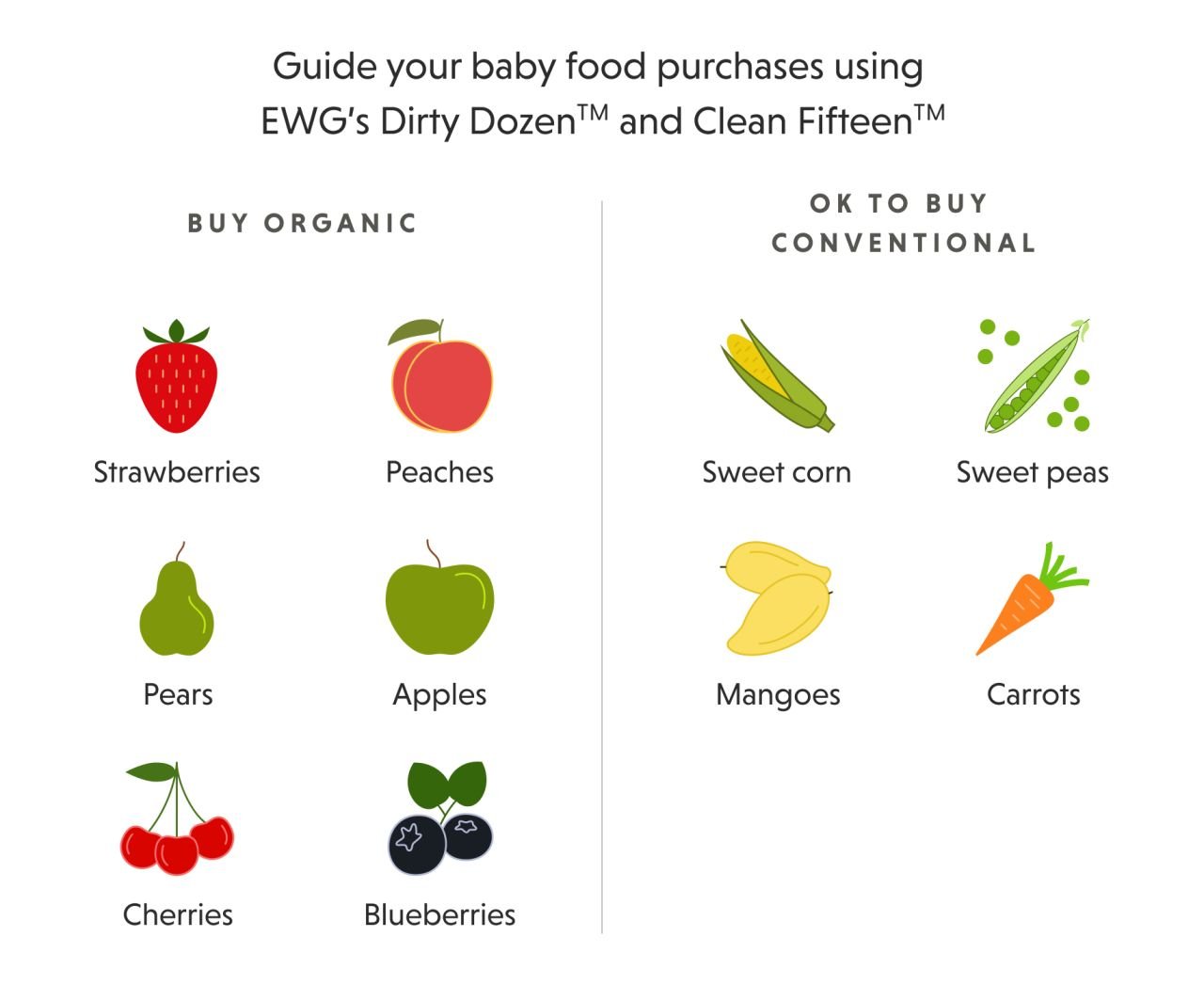

In EWG’s 2023 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce™, apples were identified on the Dirty Dozen™which lists produce with the most pesticide residues. The Shopper’s Guide, released annually, analyzes Department of Agriculture and Food and Drug Administration tests to identify which fruits and vegetables have the highest and lowest amounts of pesticide residues.

We suggest shoppers read baby food labels when choosing what to buy, because we discovered several products for which apples were listed as an ingredient but not advertised as a key flavor.

In addition to apples, blueberries, pears and strawberries are other items on the 2023 Dirty Dozen that are more likely to be found along with pesticides in non-organic baby food.

Which ingredients suggest lower amounts of pesticides in baby food?

EWG’s Shopper’s Guide also includes the Clean Fifteen™, our roundup of fruits and vegetables with low or no traces of pesticides. Our new baby food tests found that products that primarily contain peas and sweet potatoes, both on the 2023 list, did not have any pesticides in them.

EWG’s tests might not tell the whole story: Pesticide residue levels could vary significantly in other types of baby food or in different samples of the same product, and the report's appendix has more details on our testing and findings.

Recommendations for parents and caregivers

For those concerned about pesticides in baby food, EWG offers several recommendations:

- Opt for organic over conventional, when budget and availability allow. Choosing organic products remains one of the best ways to reduce your baby’s exposure to pesticides. None of the 15 organic items we sampled had any detections of these substances.

- Check ingredient labels against the Clean Fifteen and Dirty Dozen and choose products that don’t contain produce linked to higher pesticide residues.

That’s also what the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends for parents concerned about their children’s exposure to pesticides.

EWG’s latest round of tests did not detect pesticides in any conventional products made only with Clean Fifteen ingredients. These specific blends may not be available everywhere, but the Clean Fifteen can help you prioritize the non-organic options in your store. - You can also use the Clean Fifteen and Dirty Dozen to guide you if you’re making your own baby food from scratch.

Advocacy works

Our latest research proves that advocacy works. Since EWG’s first major study of pesticides in baby food was released nearly 30 years ago, we’ve campaigned for change.

Our study and the 1993 NAS report helped spur Congress to pass, and President Bill Clinton to sign, the Food Quality Protection Act, or FQPA, in 1996. The law revolutionized how we think about the threat posed by pesticides to children and required the EPA to ensure a “reasonable certainty” of no harm to infants and children from exposure to pesticide residues.

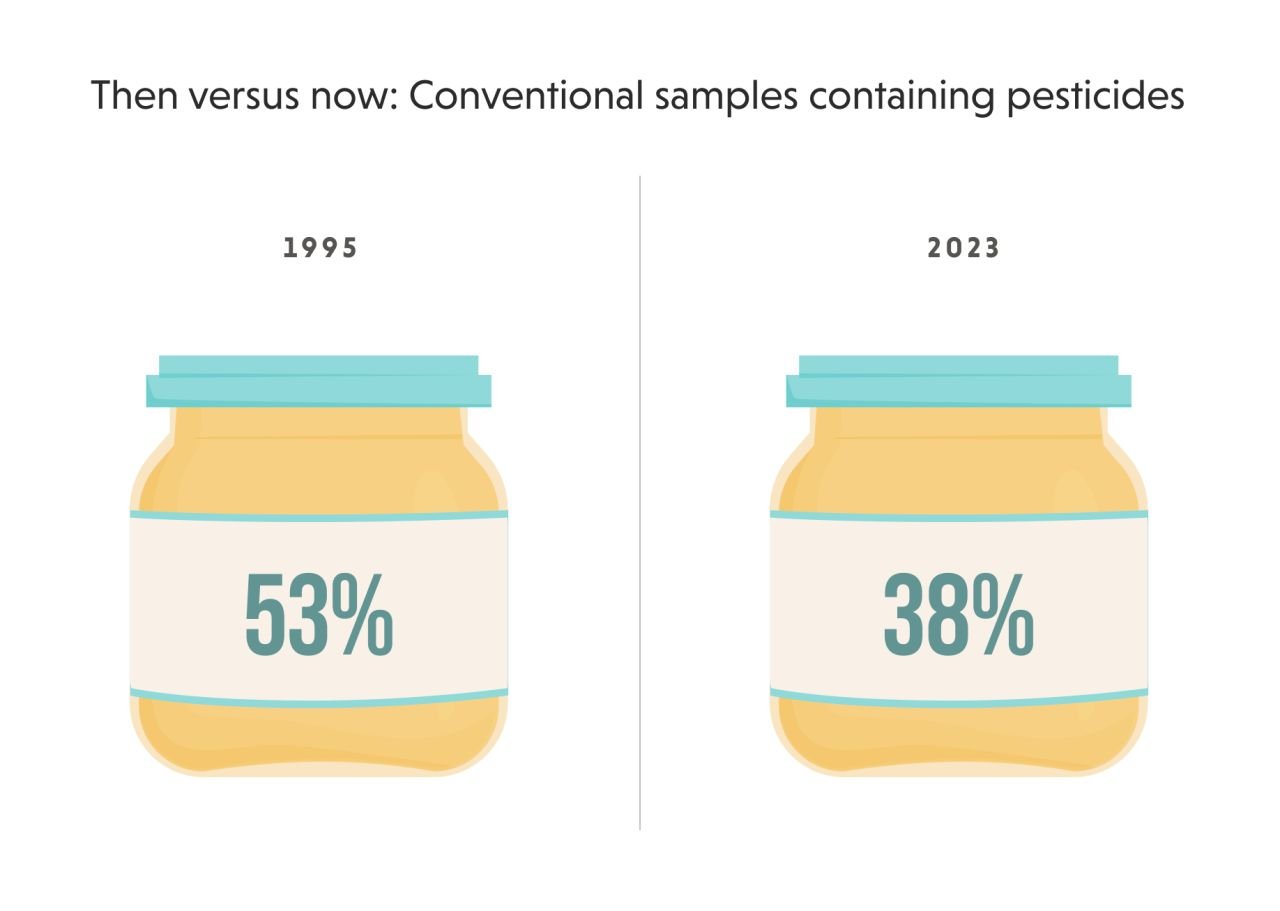

The law has worked – at least somewhat. In our 1995 study, an eye-popping 53 percent of 72 baby food products sampled had residue of at least one pesticide. That’s 15 percent higher than what we found in the products tested this year.

The pesticides those tests discovered were, overall, far more toxic and dangerous for infants to ingest than the ones our latest tests uncovered.

One toxic pesticide we no longer found in baby food was the brain-damaging bug killer chlorpyrifos, which in very small amounts can permanently damage the health of babies and children.

The EPA finally banned all uses of chlorpyrifos on food in 2021, a move EWG had advocated for years.

Another toxic pesticide, acephate, detected in EWG’s 1995 study is so harmful to human health that the EPA banned it from use on green beans in 2011. Our latest tests found no traces of it.

These positive changes are proof that the regulatory system can work to better protect our health.

But the EPA’s use of the FQPA has been inconsistent. And a peer-reviewed study EWG published in 2020 found that the EPA fails to follow guidelines set by the FQPA to adequately protect children from the health harms posed by pesticides in food.

EWG will continue its research on pesticides and children’s food, because much more work remains.