Summary

America’s prairies and wetlands are being lost at an astonishing rate.

Between 2008 and 2011, farmers plowed under more than 23 million acres of grassland, shrub land and wetlands to plant crops such as corn, soybean and wheat – an area the size of Indiana. America lost more wetlands and prairie in those four years than in the previous 40.

At the same time, polluted runoff from agriculture is threatening drinking water supplies. Fertilizer, pesticides and sediment that run off poorly managed farm fields dramatically increase drinking water treatment costs and threaten the livelihood of fishermen and the economies of rural communities that depend on clean water.

The reality is that the nation’s primary prairie and wetlands protection program – the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) – was not designed to meet the environmental challenges being created by record prices for farm commodities. Because the majority of the land in the program is taken out of agricultural production under 10- and 15-year rental agreements with the owners, cropland that had been “restored” with grasses and trees is increasingly being plowed under to grow crops again as soon as these agreements expire. As a result, the benefits of taxpayers’ investment in these short-term agreements have proved to be fleeting.

By contrast, lands that were restored through long-term agreements through a similar but much smaller program administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have provided more permanent benefits – at comparable cost to the taxpayer. Similarly, land restored through enrollment in certain special CRP initiatives1 and through the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program2 has also been less likely to be plowed under when rental contracts expire, according to an EWG analysis.

Important changes must be made to the program in the 2013 farm bill to withstand the current economic incentives to plow up every available acre. In particular, lawmakers should focus future CRP land enrollment through the special initiatives that have proved to provide more durable natural resource and environmental benefits. Most important, landowners should have the option to protect their land through long-term and permanent easements. These reforms would deliver longer lasting environmental benefits and provide a greater return on investment for taxpayers.

Paradise Lost

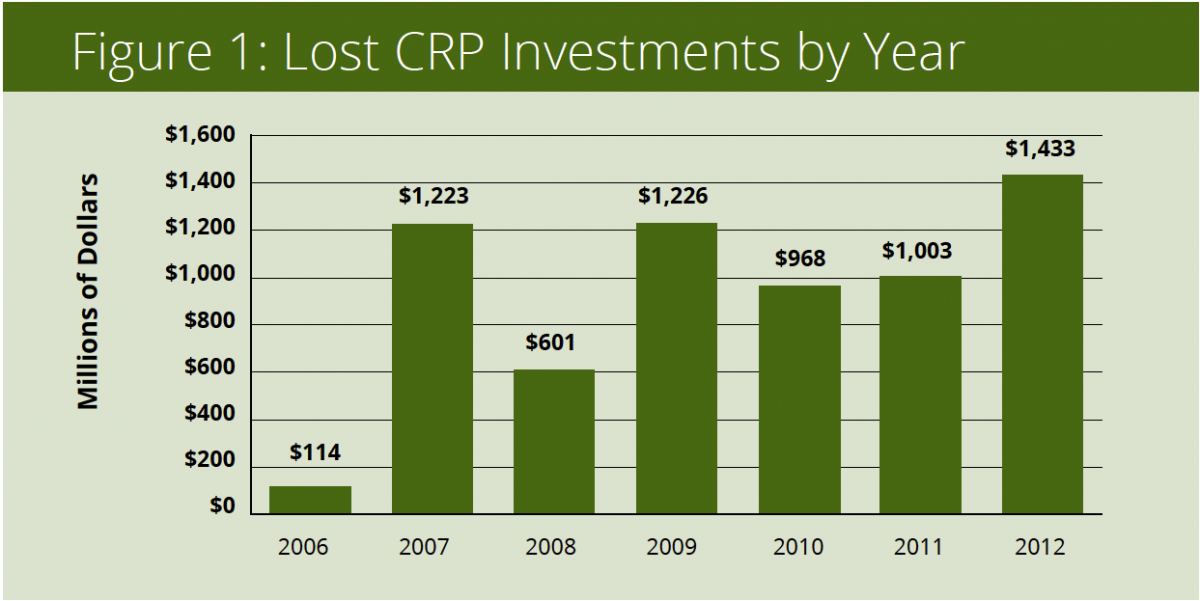

Between 2006 and 2012, 14 million acres that had been protected by CRP likely went under the plow again as short-term rental agreements between landowners and USDA expired. EWG estimates that the taxpayers paid landowners at least $6.6 billion to rent and restore these 14 million acres to grasses and trees for a limited 10-year period. Now, however, the conservation benefits that taxpayers sought and paid for have been squandered3. Drinking water is threatened again and essential wildlife habitat is being lost. Even as these 14 million acres were dropping out of the program, taxpayers rented 7.5 million “new” acres – which also may well be plowed up as those rental agreements expire.

Land in 10 Midwestern states accounted for nearly three-fourths of the land that had been protected by the program and has now been returned to agricultural production –North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Colorado and Texas. Much of this land is concentrated along the northern and western edges of the “corn belt” and provides critical habitat for waterfowl and endangered species, including the iconic sage grouse. Returning these lands to crop production is threatening wildlife species, increasing water pollution and releasing significant amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

Better Investments

A better course would be to protect more acres through special initiatives that have proved to produce more durable conservation benefits. In particular, Congress should reform the Conservation Reserve Program to set aside 600,000 acres annually for CRP’s “continuous enrollment” categories and for protection under state-led Conservation Reserve Enhancement Programs (CREPs). These initiatives have been able to continue increasing the number of protected acres even in the face of increased pressure to expand crop production.

In addition, Congress should give farmers the option of enrolling land through 30-year CRP agreements or permanent easements. Other government programs demonstrate that long-term protection can be achieved at comparable cost to CRP’s short-term agreements. A similar program administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has provided long-term protection to lands in the Dakotas at an average cost of $427 an acre. By contrast, the average cost of a 10-year CRP rental agreement in the Dakotas is $417 an acre, according to EWG’s analysis. Offering farmers longer-term options would give taxpayers a better return on their investment and do much more to provide clean water, lower atmospheric carbon and protect wildlife.

Although farmers should retain the option of renting land to taxpayers for just 10-to-15 years, these short-term agreements are producing a poor return on investment. As EWG’s analysis demonstrates, many acres of land that have been “restored” with grasses and trees are quickly returned to crop production when landowners see an opportunity to profit from spikes in commodity prices. To protect the taxpayer and the environment, Congress should reform the Conservation Reserve Program so as to secure longer-term protection of environmentally important land and produce more durable conservation benefits.

The full map is located here: http://a.tiles.mapbox.com/v3/ewg.CRP.html#6.00/38.959/-97.800

Footnotes:

1CRP’s “continuous sign-up” initiative allows landowners to easily enroll and restore especially valuable lands, including riverside buffers, wetlands and strips of grass designed to intercept and filter polluted runoff.

2The Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) matches CRP funds with state and private funds to restore especially valuable lands, often through easements. Many CREPs are designed to protect important drinking water sources or endangered species habitat.

3This is a conservative estimate because taxpayers may have rented the land for more than ten years.

Acknowledgements:

EWG thanks the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, The Walton Family Foundation and The McKnight Foundation for their support for this project.