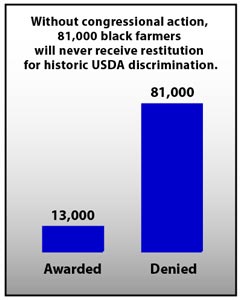

A new investigation by Environmental Working Group (EWG) and the National Black Farmers' Association (NBFA) finds that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) willfully obstructed justice by deliberately undermining the terms of a 1999 landmark civil rights settlement with African American farmers. As a result, the vast majority of African American farmers have been denied compensation that the court, in approving the settlement, described as "automatic." For the 81,000 farmers denied compensation, there is no future opportunity to obtain relief. Even though USDA has admitted to civil rights abuses, it withheld some three quarters of the $2.3 billion that the settlement was worth. Without intervention by the United States Congress, these farmers will never receive the compensation they so clearly deserve. [Document: Pigford v. Veneman Opinion]

Specifically we found that:

• Nearly nine out of ten denied restitution. USDA denied payment to 86 percent, or 81,000 out of 94,000, African American farmers who came forward seeking restitution.

• 56,000 hours spent fighting farmers. USDA aggressively fought claims by African American farmers, contracting with United States Department of Justice lawyers who spent at least 56,000 staff hours and $12 million contesting individual farmer claims for compensation.

The 81,000 denials took two forms:

• Deadline barred 64,000 claims, despite lack of notice. The settlement-funded arbitrator rejected 64,000 farmers who came forward with claims during the late claims process established by the court. The farmers' attorneys, whose representation was characterized by the court as "bordering on legal malpractice," were responsible for properly notifying the farmers of the original deadline for application. The settlement-funded arbitrator rejected these 64,000 farmers simply on the basis of their tardiness for the original deadline, even though all 64,000 rejected claims were submitted within the court established late claims period. An additional 7,800 farmers failed to file before the late claims deadline expired and were also denied entry to the class.

Top 10 States: Farmers seeking entry under court-mandated extension

See data for all 50 states

State Rejected Granted Total Mississippi 18,983 286 19,269 Alabama 14,268 294 14,562 Tennessee 4,642 24 4,666 North Carolina 2,448 1,012 3,460 Oklahoma 3,309 51 3,360 Georgia 3,228 81 3,309 Illinois 2,864 29 2,893 Louisiana 2,312 21 2,333 South Carolina 1,826 70 1,896 California 1,495 30 1,525 National Total 63,816 2,131 65,947 Note: Data in this table is based upon information received from the Office of the Monitor on April 26, 2004.

• 9,000 denied "automatic" award. Of the 22,000 farmers granted access to the class, in what the court referred to as "automatic" payment status, USDA denied payment to 40 percent, or 9,000 farmers. Entry to the class was not guaranteed, but depended on a farmer proving that he/she applied for a USDA loan between 1981 and 1996, that USDA's response was racially discriminatory, and that the individual filed a discrimination complaint arising from USDA's treatment of the application. All of the 9,000 farmers denied payment by USDA met these criteria, but received nothing.

Nearly 9,000 Black farmers were denied "Automatic" payments by USDA — Top 10 States

| State | Number Eligible | Receiving "Automatic" Awards |

Denied "Automatic" Awards |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | ||

| Alabama | 4,511 | 3,096 | 69% | 1,415 | 31% |

| Mississippi | 4,373 | 2,643 | 60% | 1,730 | 40% |

| Georgia | 2,960 | 1,757 | 59% | 1,203 | 41% |

| North Carolina | 1,989 | 910 | 46% | 1,079 | 54% |

| Arkansas | 1,986 | 1,293 | 65% | 693 | 35% |

| South Carolina | 1,274 | 793 | 62% | 481 | 38% |

| Louisiana | 991 | 478 | 48% | 513 | 52% |

| Oklahoma | 794 | 541 | 68% | 253 | 32% |

| Tennessee | 663 | 407 | 61% | 256 | 39% |

| Florida | 472 | 248 | 53% | 224 | 48% |

|

|

|||||

| National Total* | 22,181 | 13,411 | 61% | 8,770 | 40% |

* Note: Information in this table is based upon data received from the Office of the Monitor on 4/26/2004. The 7/12/2004 report from the Office of the Monitor states that the total number of awards received is now 13,429.

"I've talked to more people that haven't even heard anything at all, and more people that got denied, than I have talked to people who got the $50K and a partial debt write-off. And now the USDA seems to be just sitting still."

— Alan Diggs,

Southampton, VA farmer

In this historic civil rights case, known as Pigford v. Veneman, USDA promised to pay billions to African American farmers who claimed that the USDA had systematically discriminated against them for decades, denying them access to essential crop loans that were made readily available to "similarly situated" white farmers in their communities. The settlement was largely based on USDA's own admission of discrimination in its 1997 civil rights study, and the Reagan Administration elimination of the USDA's Office of Civil Rights in 1983, effectively denying African American farmers any recourse for claims of discrimination from 1983 through 1996, when the Office was reestablished. In part due to lack of equal access to USDA loans, the number of farms operated by African Americans has declined dramatically over the past 20 years, plummeting from 54,367 in 1982 to just 29,090 in 2002.

Recommendations

This willful obstruction of justice by the USDA demands immediate action on the part of the U.S. Congress. Only the Congress can make whole the farmers who were denied restitution arbitrarily, after the USDA had agreed, in settling the case, that their discrimination claims were valid.

EWG and NBFA recommend that USDA and the U.S. Congress immediately take action to remedy these inequities by taking the following measures:

(1) Congress should order USDA to provide full compensation to the nearly 9,000 farmers who were denied relief after being accepted into the settlement class;

(2) Congress should order USDA to re-evaluate the merits of the nearly 64,000 farmers' claims that were shut out due to lack of notice of the settlement. All African American farmers who meet the preliminary requirements to qualify as a member of the Pigford class should receive the $50,000 payment and debt relief provided by the settlement;

(3) Congress should direct the USDA to institute accountability measures to monitor and enforce civil rights standards throughout the Agency, requiring that in the future the USDA shall exert best efforts to ensure compliance with all applicable statutes and regulations prohibiting discrimination; and

(4) Congress should ensure the full implementation of outreach and financial assistance programs that support minority farmers.

A Century of USDA's Institutionalized Racism Subjects African American Farmers to Dramatic Land Loss

In 1920, one in every seven farms was African American owned. Today, only 1 in 100 farms is African American owned (USDA 1998, at 16). The decline of the African American farmer has taken place at a rate that is three times that of white farmers (USDA 1998, at 16-17).

"I never even got the chance to start the chicken farm like I wanted. I just gave up."

—Leroy McCray, Sumter County, SC farmer

Though many causes contribute to the decline of the African American farmer, the racial disparity is unmistakable. Institutionalized racism within the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) played a major part in this phenomenon. Indeed, the USDA Commission on Small Farms admitted that "[t]he history of discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture ... is well documented," finding that "indifference and blatant discrimination experienced by minority farmers in their interactions with USDA programs and staff ... has been a contributing factor to the dramatic decline of Black farmers over the last several decades" (NCSF 1998).

Although the civil rights movement successfully eradicated facially discriminatory laws, institutionalized racism remained and carried on the legacy of racial discrimination. In the USDA, it took the form of all-white county committees and apathetic federal offices failing to address the problem. Further, in 1983, due to Reagan Administration budget cuts, the USDA Office of Civil Rights was dismantled, and USDA stopped processing all discrimination claims until 1996, when the office re-opened (Pigford 1999, at 85). During this period, the USDA Office of Civil Rights Enforcement and Adjudication (OCREA) "simply threw discrimination complaints in the trash without ever responding to or investigating them," and in some cases, "even if there was a finding of discrimination, the farmer never received any relief."

In 1996, USDA set out to address this problem, forming the Civil Rights Action Team, which was charged with making recommendations for eradicating racial discrimination within the USDA (Pigford 1999, at 88). The Civil Rights Action Team report exposed a history of discrimination that persisted even in 1996, finding that "minority farmers have lost significant amounts of land and potential farm income as a result of discrimination by [USDA]." It found racial disparities in disapproval rates for loans and processing times, extreme lack of diversity on the county committees responsible for administering USDA programs, and revealed a civil rights complaints system that had been effectively inoperative since its inception. The report made numerous recommendations for addressing these problems—many have yet to be implemented.

African American Farmers Sue USDA for Racial Discrimination

Pigford v. Veneman — African American Farmers Turn to the Courts for Justice

When the USDA failed to implement its own recommendations for addressing the persistent racism in the administration of its programs, African American farmers turned to the courts in hopes of finally addressing this monumental injustice. Among these lawsuits was Pigford, et al. v. Veneman, 97 Civ. 1978, 98 Civ. 1693 (PLF), a case brought by three farmers on behalf of all African American farmers who had been victims of racial discrimination at the hands of the USDA. Pigford would prove to be a landmark case, and, unfortunately, a study on how a federal agency can evade accountability despite admitting to wrongdoing and agreeing to compensate its victims.

"The way it usually works is that you would file for FSA assistance in February. You're supposed to get your money in March or April in order to have enough resources to plant on time to reach harvest before the fall rains and frost come. White farmers were getting their money on time, every time. But not the black farmers."

—Leon Pulley, Butler County, MO farmer

On August 28, 1997, farmer Timothy Pigford filed a class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia against the Secretary of Agriculture, Dan Glickman, alleging that USDA discriminated against African American farmers by denying or delaying applications for benefit programs and by mishandling the discrimination complaints filed with the Department. [Document: Complaint] The case was assigned to Judge Paul Friedman, who, on October 9, 1998, certified the Pigford class, allowing the case to move forward as a class action.

Concerns about the expiration of the statute of limitations loomed over the case, threatening to bar the farmers' claims from ever being heard in court. After African American farmers and their supporters presented testimony before Congress, a bill was passed suspending the statute of limitations, which President Clinton signed into law on October 21, 1998.

With this matter resolved, the African American farmers and the USDA continued in their settlement discussions. From the beginning of the case, the parties had discussed settlement under the direction of a mediator. They faced several struggles in the settlement process. A key point of controversy between the farmers and the USDA involved the structure of the potential settlement. The parties engaged in contentious debate, both before the mediator and before Judge Friedman, over whether to structure an agreement which settled all of the farmers' claims at once or whether to construct a process which would resolve the claims on a case-by-case basis. The attorneys for the farmers were concerned that a case-by-case process would drag on for years and further delay justice for the farmers. After much debate, nearly two years after the complaint was filed, the parties entered into a settlement, filing their version of the agreement, the Consent Decree, with the Court on March 19, 1999. [Document: Consent Decree]

The Consent Decree set forth a revised class definition and a two-track system for resolving claims on a case-by-case basis. All individuals who fit within the following definition were considered members of the class:

All African American farmers who:

(1) farmed, or attempted to farm, between January 1, 1981 and December 31, 1996;

(2) applied to USDA during that time period for participation in a federal farm credit or benefit program and who believed that they were discriminated against on the basis of race in USDA's response to that application; and

(3) filed a discrimination complaint on or before July 1, 1997, regarding USDA's treatment of such farm credit or benefit application. [Excerpt: Class Definition | Full Document: Consent Decree]

The system designed by the parties for resolving claims took the form of a two-track dispute resolution mechanism, with two separate processes through which African American farmers in the class could pursue claims. Under the more streamlined process, Track A, a farmer could prevail with minimal documentation, but recovery is limited to $50,000. The alternative process, Track B, would be more like a civil trial, requiring more extensive documentary evidence, but providing farmers with the opportunity to obtain cash payments based on actual damages without a cap on the award.

Successful farmers in both tracks would also be eligible for non-cash relief, including tax assistance, debt forgiveness, foreclosure termination, technical assistance and one-time priority loan consideration. Both tracks presented all-or-nothing options — if you won you got relief, if you lost, you got nothing. The Consent Decree did not provide any appeal right, therefore, if a farmer lost the claim, the farmer had no right to have that decision overturned by a neutral party. Instead, a losing party could request that the court-appointed Monitor direct the original decision-maker to re-examine the decision. Those who did not want to accept the terms of the settlement were legally entitled to opt out of the settlement and pursue lawsuits of their own.

Pigford's Two Track Settlement Process, Tracks A and B

Track A - "Automatic" $50,000 Award

Track A was designed to provide limited relief quickly for farmers with minimal or no documentary proof. The process was to take a total of 110 days, or just over 3 months, from start to finish. The Court described this track as a "dispute resolution mechanism that provides those class members with little or no documentary evidence with a virtually automatic cash payment of $50,000" (Pigford 1999, at 95).

Farmers who are alleging racial discrimination in loan or subsidy programs are eligible for this track. In order to succeed, farmers had to present substantial evidence showing that he/she was subjected to racial discrimination by the USDA and suffered economic damages as a result. Substantial evidence was defined by the Court as, "a reasonable basis for [finding] that discrimination happened." Successful farmers would receive a $50,000 cash payment for loan-based claims or $3,000 for subsidy-based claims as well as debt relief. Loan programs, or credit benefits programs, include loans offered by the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), now part of the Farm Services Agency (FSA). Subsidy programs, or non-credit benefits programs, include commodity programs, disaster programs, and conservation programs, formerly administered by the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS), also now administered by the FSA.

Under Track A, the process should proceed as follows:

- farmer submits a claim package to Facilitator, choosing Track A. Claim packages must include all documentation and evidence supporting class membership and proving claim.

- Within 20 days of receiving the package, Facilitator determines whether farmer is a class member and assigns a track, then forwards notice to the Adjudicator, USDA and class counsel.

- Within 60 days of receiving notice USDA may submit information relevant to liability or damages to Adjudicator and class counsel.

- Within 30 days of receiving material from farmer and USDA, Adjudicator decides whether claim is supported by substantial evidence, stating the reasons for the decision. Adjudicator must evaluate whether the farmer has presented substantial evidence to show the following:

(1) farmer owned or leased, or attempted to own or lease farm land,

(2) farmer applied for a loan or subsidy transaction at a USDA office between January 1, 1981 and December 31, 1996,

(3) the application was denied, provided late, approved for a lesser amount than requested, encumbered by restrictive conditions, or USDA failed to provide appropriate service,

(4) treatment received was less favorable than that accorded to a specifically identified, similarly situated white farmer, and

(5) USDA's treatment caused farmer economic damages. - Successful loan program claimant receives $50,000 payment and debt relief from USDA. Successful subsidy program claimant receives $3,000 payment and debt relief from USDA. (Losing party may request that the Monitor direct the Adjudicator to re-examine claim where clear, manifest error has occurred that has resulted or is likely to result in a fundamental miscarriage of justice.)

- Maximum time from submission of claim to decision: 110 days.

Track B — Evidence-Based Proceeding to Recover Actual Damages

Track B was designed to offer an abbreviated trial procedure and an accurate damages award for farmers with superior documentation of their claim. This process, though expanded, was designed to take a maximum of 240 days, or 8 months, from claim submission to decision. Only farmers with claims arising from loan, or credit program, transactions were eligible for this track. Track B farmers had to prove their claims and actual damages by the standard civil litigation burden of proof, "preponderance of the evidence," showing that it is more likely than not that their claim was valid (Pigford 1999, at 95). Successful farmers would be entitled to receive monetary damages as proven, and non-cash relief.

Under Track B, the process should proceed as follows:

- Farmer submits a claim package to Facilitator, choosing Track B.

- Within 20 days of receiving the package, Facilitator determines whether farmer is a class member and assigns a track, then forwards notice to Arbitrator, USDA and class counsel.

- Within 10 days of receiving claim package, Arbitrator notifies farmer and USDA of date of evidentiary hearing. Hearing date to be set within 150 days of sending notice, but may not be set for less than 120 days after notice is sent.

- 90 days prior to hearing date, parties serve on each other witness lists, statements of intended testimony of witnesses, and copies of exhibits to be presented at arbitration hearing.

- 45 days prior to hearing date, parties complete depositions of opposing party's witnesses.

- 30 days prior to hearing, parties file with Arbitrator and serve on each other written versions of direct testimony of witnesses.

- 21 days prior to hearing date, parties notify each other of witnesses whom they intend to cross-examine at trial. Also by this date, parties file memoranda of law and fact with Arbitrator.

- Hearing (eight hours)—four hours of cross-examination of opponent's witnesses and presenting legal arguments for each party.

- Within 60 days of hearing, Arbitrator issues written decision as to whether farmer has demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that farmer was a victim of racial discrimination and suffered damages as a result.

- Successful farmer receives actual damages from USDA. (Losing party may request that the Monitor direct Adjudicator to reexamine claim where clear, manifest error has occurred that has resulted or is likely to result in a fundamental miscarriage of justice.)

- Maximum time from submission to decision: 240 days.

Court's Fairness Review and Consent Decree Approval

The Court reviewed the settlement for fairness, considering objections and responses of the African American farmers and USDA, and approved the Consent Decree in an opinion dated April 14, 1999. Numerous class members, civil rights organizations and farmer organizations filed objections to the Consent Decree and testified at the fairness hearing. [Document: NBFA objections] Overall, the Court received objections from 15 organizations and 27 individuals, including two named plaintiffs, Timothy Pigford and Cecil Brewington. Farmers voiced concerns about many aspects of the Consent Decree, including the amount of recovery provided to the farmers in the settlement, the structure of the dispute resolution mechanism, and the lack of forward-looking relief. After considering the objections and comparing the settlement outcome with the likelihood of prevailing at trial, the Court determined that the settlement would provide a fair, efficient tool for redressing the farmers' grievances.

"You got to choose one or the other track, your choices are simple, you either take the $50,000 or you gamble that you might get more and wait it out. It wasn't an easy decision, I didn't want to just take the $50,000. I wanted to go for the $5 million they had denied me, but it seemed like it would never be resolved if I did that."

—Leroy McCray, Sumter County, SC farmer

Much of the Court's analysis hinged on the fair and efficient administration of the settlement process. In discussing the fairness of the amount of recovery provided in the settlement, the Court reasoned that farmers largely lacked documentary evidence to prove their claims and that "the settlement negotiated by the parties provides for a relatively prompt recovery" compared to trial, where, "it is unlikely that any class member would have received any recovery for his injury for many years" [Document: Fairness Opinion] (Pigford 1999, at 104-105).

In addressing objections to the requirement that Track A farmers show proof that they fared worse than "a specifically identified, similarly situated" white farmer, the Court found that the requirement was not overly burdensome because the plaintiffs' lawyers had obtained information on a number of white and African American farmers from USDA (Pigford 1999, at 106). Thus, the Court opined, "class counsel should be able to provide most farmers with the evidence they need" (Pigford 1999, at 106).

When the Court considered objections to Track B's lack of a discovery procedure requiring parties to exchange documents, the Court maintained that this was a fair concession since "the Track B mechanism ... resolves the claim much more quickly than an ordinary civil case would be resolved, in large part because of the shortened discovery period" (Pigford 1999, at 106). In resolving that the lack of an appeal procedure was fair, the Court focused on the expectation that most farmers would succeed in the settlement, stating, "[s]ince it is anticipated that most class members will prevail under the structure of the settlement, the Court concludes that the forfeit of the appeal rights was a reasonable compromise" (Pigford 1999, at 108).

The Court was "surprised and disappoint[ed]" by USDA's refusal to include the following sentence in the Consent Decree: "In the future the USDA shall exert best efforts to ensure compliance with all applicable statutes and regulations prohibiting discrimination" (Pigford 1999, at 111-112). Though the Court acknowledged that the farmers "legitimately fear that they will continue to face...discrimination in the future," the Court reasoned that the settlement was fair because "USDA is obligated to pay billions of dollars to African American farmers who have suffered discrimination...those billions of dollars will serve as a reminder to the Department of Agriculture that its actions were unacceptable and should serve to deter it from engaging in the same conduct in the future" (Pigford 1999, at 111). Finally, the Court determined that future discrimination would be curtailed because USDA would be under intensified scrutiny of the Courts, Congress, and the African American farmers as a group, all of which are equipped, according to the Court, to address future discriminatory practices discovered within USDA.

In approving the Consent Decree, the Court had described the settlement as an agreement that would "achieve much of what was sought without the need for lengthy litigation or uncertain results" (Pigford 1999, at 95).

USDA Settlement Fails Black Farmers

Denials and Delays Prevail

The current state of play in the settlement presents a far different picture than the predictable, efficient process envisioned by the Court. Instead of predictable results and shortened process, the settlement has yielded a remarkably high rate of rejection for farmers who chose Track A and a contentious, protracted proceeding for those who elected Track B.

"It was common knowledge that certain white farmers got better treatment. Everyone knew that the white farmers were getting loans while we weren't. They were not far from us, just down the road, and it was just generally known that they were getting money from FSA but we weren't."

—Calvin King, Lunenburg County, VA farmer

Overall, of the nearly 100,000 farmers who came forward with racial discrimination complaints, 9 out of 10 were denied any recovery from the settlement. As a result, instead of the $2.3 billion, USDA only provided $650 million in direct payments to farmers. The outcome of the settlement suggests that the farmers who had the best chance at achieving justice were the 230 who opted out of the settlement.

The settlement looks quite different than originally expected. Prior to advertising the lawsuit to reach potential class members, the farmers' attorneys had predicted that the class would number 2,000. This estimation was far from accurate, largely because USDA kept such poor records of civil rights complaints. There are now 22,354 farmers who have been accepted into the settlement class, 22,181 in Track A and 173 in Track B (Pigford Monitor 2004). There are even more, some 73,747 farmers, who sought entry into the settlement through a late-claims process (Pigford Arbitrator 2004, at 2-3).

African American farmers have faced high rates of denial in both tracks. Of the 22,181 farmers assigned to Track A, 8,562 or 40 percent, have been denied (Pigford Monitor 2004). As for Track B, of the 173 eligible farmers, 18 farmers, a mere 10 percent, have prevailed after a hearing (Pigford Monitor 2004a). Sixty-eight settled with USDA prior to obtaining a decision. Thirty-nine farmers had their cases dismissed without a hearing. Another 22 lost after a hearing.

According to the Office of the Monitor, 190 Track A farmers (Pigford Monitor 2004) and 23 Track B farmers are still awaiting decisions, 20 of whom have not yet had even an initial hearing (Pigford Monitor 2004a), over 5 years after the Consent Decree was entered.

Table. Denials and delays in Track B Outcomes

| Farmer Status* | Number of Farmers |

|---|---|

| Total Number of Farmers in Track B | 173** |

| Farmers Who Won After Hearing | 18 |

| Farmers Who Were Dismissed | 61 |

| - Dismissed Prior to Hearing | 39 |

| - Dismissed After Hearing | 22 |

| Farmers Awaiting Initial Hearing | 20 |

| Farmers Awaiting Arbitrator Decision | 3 |

| Farmers Receiving Negotiated Settlement Compensation Prior to Hearing | 68 |

*The Farmer Status information is based on information received from the Office of the Monitor on June 11, 2004.

**This Total Number of Farmers in Track B figure is based on the Pigford Monitor Report of July 12, 2004.

Lack of Notice Prevents 72,000 Farmers from Joining Settlement

When thousands of farmers came forward with claims of discrimination after the settlement-imposed deadline, it became evident that notice of the settlement was insufficient to reach the majority of potential class members. Farmers had difficulty meeting deadlines in all aspects of the settlement, largely due to the failure of their lawyers to comply with the required timelines and communicate with the farmers. The Court admonished the farmers' lawyers for their failure to meet deadlines, even going so far as to state at one point that their representation "border[ed] on legal malpractice" (Pigford 2002, at 922).

The farmers' lawyers were responsible for providing adequate notice to all putative class members. The flood of late claims indicates that the notice failed to reach thousands of farmers with claims against USDA. The Court-approved late claims process provided for entry into the settlement process upon demonstrating extraordinary circumstances that prevented the farmer from meeting the original deadline. Acceptable reasons for late filings included natural disasters and being homebound (Pigford Arbitrator 2001, at 4), but not lack of notice of the settlement.

A flood of farmers, numbering 73,747, sought late entry into the settlement process (Pigford Arbitrator 2004, at 2-3). Of this 73,747, 65,947 farmers filed their applications on time (Pigford Arbitrator 2004, at 2-3). The overwhelming majority of the farmers who did apply on time, some 63,816 farmers, were ultimately denied entry into the settlement (Pigford Arbitrator 2004). Their claims were never heard on the merits, and they will never again have a chance to seek relief for their discrimination complaints.

Top 10 States: Farmers seeking entry under court-mandated extension

| State | Rejected | Granted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | 18,983 | 286 | 19,269 |

| Alabama | 14,268 | 294 | 14,562 |

| Tennessee | 4,642 | 24 | 4,666 |

| North Carolina | 2,448 | 1,012 | 3,460 |

| Oklahoma | 3,309 | 51 | 3,360 |

| Georgia | 3,228 | 81 | 3,309 |

| Illinois | 2,864 | 29 | 2,893 |

| Louisiana | 2,312 | 21 | 2,333 |

| South Carolina | 1,826 | 70 | 1,896 |

| California | 1,495 | 30 | 1,525 |

|

|

|||

| National Total | 63,816 | 2,131 | 65,947 |

Note: Data in this table is based upon information received from the Office of the Monitor on April 26, 2004.

USDA Pays DOJ Millions to Fight Farmers' Claims

USDA contracted with the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) to provide legal representation in the settlement. DOJ internal documents reveal that the Civil Division spent 56,000 hours of attorney and paralegal time challenging 129 farmers' claims. [Document: DOJ timesheets] This amounts to an average of 460 hours, or nearly 3 months of time, devoted to contesting each individual farmers' claim. Assuming an average salary of $60,000, if this amount of time was spent attacking the claims of all 22,000 farmers in the class, this represents a potential cost of $330 million to taxpayers. That is equivalent to the cost of providing Track A relief for 6,600 farmers.

Overall, USDA spent $12 million by 2002 for DOJ's assistance in disputing individual farmers' claims. [Document: USDA Expenses] These numbers are extraordinarily high for a settlement that was intended to provide a "virtually automatic" payment to farmers through an abbreviated procedure. Instead, it appears that African American farmers were treated as adversaries rather than as partners in a cooperative settlement.

Proceedings Lack Transparency and Accountability

Much of the transparency provided in traditional legal proceedings was lost in the Pigford matter because the case settled out of court. While the terms of the settlement agreement are public and the amounts of most settlement payments are public, details about the settlement proceedings are largely confidential.

Traditionally public documents such as transcripts of proceedings, motions of the parties and rulings of the decision-makers are not made available to the public. Farmers' attorneys have even faced difficulty in obtaining written rulings in their own cases. All attorneys who sign privacy agreements are entitled to obtain information in their farmer's case, however, because of the USDA's obstructive practices, information relating to white farmers may be omitted from the documents. This poses a serious problem, because proving the existence of a white farmer who received better treatment is vital to obtaining payment in both tracks. The farmers proceeding pro se, without legal representation, are not permitted to obtain any materials that include information on similarly situated white farmers (Pigford Monitor 2003). Without the accountability offered by transparent proceedings, plaintiffs are more vulnerable to inequities that may arise in the course of the proceedings.

| Court Trial | USDA Settlement |

|---|---|

| Public hearings | Closed hearings |

| Right to discovery documents, court-enforced information sharing | No discovery process |

| Right to appeal by neutral party | No appeal, only request for re-examination by original decision-maker |

| Public transcripts, motion papers and court rulings | Farmers' attorneys must specially request transcripts, USDA filings and rulings in their own case; without confidentiality agreements, farmers prohibited from seeing any documents; All farmers' attorneys must sign confidentiality agreements; pertinent information on case redacted by USDA |

| Publicly appointed or elected judges make decisions | Private, for-profit companies employ judges-for-hire to make decisions on claims |

USDA Conceals Key Data from Farmers

"[T]he thing I'm frustrated about...is the farmers...believed at the time of the settlement that most of them were going to get something...because we thought finding similarly situated white farmers wasn't going to be a problem. And then it turned out to be a problem."

— Judge Paul Friedman, 4/19/2001, Pigford Status Hearing

USDA constructed a major obstacle by refusing to provide African American farmers with information from its own files regarding "specifically identified, similarly situated white farmers" in their interactions with USDA. This was a key element required for relief in both tracks, and became the basis for denial of numerous claims.

USDA's practice of concealing this data left most farmers facing the task of obtaining information on similarly situated white farmers on their own. This meant tracking down a specific farmer in their county who applied for the same benefit program at the same time, with the same acreage, the same type of crop, the same credit history, and received a higher payment or better treatment than the African American farmer. This is a feat that even the most sophisticated lawyer would not be able to achieve based on public information alone. When farmers turned to USDA for information, USDA's lawyers often refused, relying on the fact that they had no obligation under the terms of the Consent Decree to release information on similarly situated white farmers to class members.

USDA repeatedly denied Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests from farmers. Thus, the African American farmers in the settlement would endeavor to obtain information using a piecemeal approach, which would provide some, but not all of the needed information. Typically, what would happen is a farmer would try to remember the names of neighboring white farmers who were farming when he/she had filed for benefits. This would provide the general pronunciation, but not necessarily the correct spelling of, the names of white farmers. Then, the farmer's attorney would run the name through public records, searching for property information such as deeds and USDA liens, which would fill in some of the information gaps. This process, however, was often inadequate, as state data systems are not uniform, and detailed information is not widely available through public avenues. Furthermore, this process is time-consuming, and often could not be accomplished within the abbreviated timeline provided by the settlement.

Throughout the course of the settlement, some measures have addressed the problem, but only to a substantially limited degree. Class counsel attorneys, since they represent large numbers of African American farmers, have been able to engage in a limited information exchange based on data gleaned from USDA responses to Track A claims. Arbitrators in Track B cases have started requiring USDA lawyers to provide information on at least three of five white farmers specifically named by farmers in the class. Of course, this still left farmers with the problem of naming such farmers on the basis of non-USDA sources.

If the cases were being litigated in civil court, there would have been rooms full of information on white farmers obtained through discovery. In the absence of documentary discovery, however, cooperation of the USDA was the only option for most farmers in the lawsuit to obtain complete information. Such cooperation was withheld. Without the assistance of USDA, the farmers have found it nearly impossible to obtain enough evidence to prove their claims.

USDA Utilizes Hard-Nosed Tactics in Track B Cases

"When we were negotiating with Counsel for the Government for the consent settlement, had I had any inkling that each claim would be litigated almost as if it was a class action unto itself, I never would have agreed to it."

— J.L. Chestnut, Attorney for African American Farmers, 4/19/2001, Pigford Status Hearing [Excerpt | Full Document]

The Track B mechanism described in the Consent Decree is a procedural shell. It included some basic provisions and deadlines, but provided scarce guidance on procedure. The Court did not adopt the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or any official set of procedural guidelines. The process essentially relied on an honors system—if both parties agreed to play fair, claimants would reap the benefits of a short, fair settlement procedure superior to the alternative of a civil trial. African American farmers in the settlement and their attorneys had no such luck.

"This same situation has happened to a lot of farmers. They [USDA] find discrimination but they won't pay. They'll fight each one to the end. They'll use taxpayer money to fight against you. The good old boy system is still in place, and working well."

—Linwood Brown, Brunswick County, VA farmer

Reports from the Office of the Monitor, which oversees all claims, note that claimants consistently complain about the "litigious nature of Track B arbitrations" (Pigford Monitor 2002, at 18). Judge Friedman even noted that USDA's conduct was not what was anticipated in the settlement, stating "I think that we all believed from the beginning...[that] the government wasn't going to file that many petitions." [Excerpt | Full Document] A petition is a challenge to a decision made in a settlement case. The USDA filed 672 challenges to decisions made in the settlements, engaging in a pattern of litigious handling of settlement claims (Pigford Facilitator 2003). During a status hearing, an attorney for the farmers expressed outrage at USDA's duplicity, "If I had known I was negotiating a situation whereby in Track B cases we would have these monumental struggles over discovery, lengthy Hornbook motions to dismiss, I never would have agreed to that." [Excerpt | Full Document]

Attorneys from large law firms in the Washington D.C. area took on a large number of Pigford cases on a pro bono basis to assist the farmers' original attorneys in processing claims. They expected a streamlined mediation process, not a trial. What they got was an elaborate motions practice, USDA appeals that repeatedly interrupted the cases, numerous evidentiary objections, delay, and aggressive litigation tactics—contentious litigation at its worst (Legal Times 2002). Attorneys found themselves spending hundreds of hours processing a single African American farmer's claim (Legal Times 2002, 2002a). The firms have devoted thousands of pro bono hours litigating this "settlement" Legal Times 2002a).

During the settlement, USDA adopted the position that farmers who missed any deadlines in their cases should face automatic rejection of their claims. In some cases, USDA lawyers would file numerous motions, causing delays in the arbitration process and missed deadlines. Once such deadlines had passed, USDA lawyers would file a motion to dismiss the case for failure to meet the deadlines.

The USDA asserted its strict deadline position in the case of Earl Kitchen, whose case was ultimately heard before Judge Friedman and then the Court of Appeals. USDA argued that the Arbitrator did not have the power to extend deadlines in settlement proceedings, thus, if a class member missed a deadline, his/her case ought to be summarily dismissed. Judge Friedman rejected this argument, finding that Arbitrators had discretion to extend deadlines (Pigford 2002a). Kitchen ultimately lost, when the Court of Appeals overruled this decision, holding that the Court can modify the deadlines only to the extent that it is justified by significantly changed circumstances (Pigford 2002).

Lawyers for the farmers also faced frivolous motions, or petitions, and hard-nosed litigation tactics at the hands of USDA's attorneys. Such tactics included agreeing to postponements then seeking dismissal for failure to prosecute. Another tactic was to seek recusal of the Arbitrator when faced with sanctions or adverse rulings. USDA has sought to overturn Arbitrator rulings in 12 of the 18 successful Track B farmers' cases (Pigford Monitor 2002, at 7).

Conclusion & Recommendations

As an agency with an annual budget of $100 billion, with nearly $40 billion (USDA 2003) designated for financial assistance to farmers, this contentious battle over paying farmers in a settled case is unjustifiable. Congressional intervention is the only solution that remains for these farmers. The U.S. Congress should step in and ensure that this discrimination comes to an end immediately. EWG and NBFA recommend that Congress remedy these inequities by taking the following measures:

(1) Congress should order USDA to provide full compensation to the nearly 9,000 farmers who were denied relief after being accepted into the settlement class;

(2) Congress should order USDA to re-evaluate the merits of the nearly 64,000 farmers' claims that were shut out due to lack of notice of the settlement. All African American farmers who meet the preliminary requirements to qualify as a member of the Pigford class should receive the $50,000 payment and debt relief provided by the settlement;

(3) Congress should direct the USDA to institute accountability measures to monitor and enforce civil rights standards throughout the Agency, requiring that in the future the USDA shall exert best efforts to ensure compliance with all applicable statutes and regulations prohibiting discrimination; and

(4) Congress should ensure the full implementation of outreach and financial assistance programs that support minority farmers.

"I've talked to farmers from all over... and it's nationwide, everybody has dealt with it. I've heard the same type of stories from Midwestern farmers all the way down south. There's a lot of things that still need to happen, still a lot of things the USDA needs to make right."

—Alan Diggs, Southampton County, VA farmer

The history of discrimination that led to the Pigford suit tells the tale of deeply entrenched institutionalized racism. The discrimination that led to the suit still persists in many forms, including even the administration of a civil rights settlement. Instead of a fair facilitation of the settlement, the victimization continues with delay tactics and aggressive litigation strategies. A settlement is a cooperative process, not a small-scale litigation battle. Ultimately, the farmers have not fared substantially better than they would have at a civil trial. A startling 86% of the farmers with discrimination complaints have been unsuccessful and walked away from the settlement with no money and no ability to redress their grievances in a court of law. As for Track B claimants, lengthy litigation and uncertain results are the reality of this settlement. Only 18 claimants of nearly 200 have been successful before the Arbitrator and 20 still await the initial hearing over five years after the settlement was reached. This is not a favorable alternative to civil trial. On the contrary, it is a continuation of the disenfranchisement of the African American farmer at the hands of the USDA.

Small farmers, the group of farmers to which most African American farmers belong, are the backbone of our sustainable agricultural future. By contributing a heightened awareness of the needs of the land, utilizing sustainable practices such as multicropping, and by supporting the growth and wealth of their local communities, small farmers provide an invaluable resource to the agricultural system. Government-subsidized loans and grants are designed to support the small farmer, and provide vital resources to this important segment of the farming industry. In order for this system to operate effectively, it must operate equitably. To discriminate against small farmers, and to further marginalize particular small farmers with racially discriminatory practices in the administration of financial assistance, contravenes the spirit and purpose of these USDA programs.

UPDATE: USDA Refuses to Own Up to Failings of Settlement with African American Farmers

Instead of taking responsibility for the failures of the out-of-court settlement with African American farmers for racial discrimination in its loan and subsidy programs arising from the Pigford v. Veneman case, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has attempted to deflect attention from its wrongdoings by blaming the settlement's shortcomings on the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and the private entities it hired to run the program. In response to a renewed public interest in the progress of the settlement, and in defending a second racial discrimination class action, USDA has claimed that the private monitors are solely responsible for the settlement's surprisingly high denial rates, and that DOJ is preventing USDA from addressing any of the settlement's problems. USDA's response is disappointing and disingenuous. In fact, USDA has spent at least $12 million dollars challenging successful settlement claims. USDA was responsible for the behavior that led to the settlement, and has the duty to ensure that the settlement fairly compensates African American farmers for their resulting losses.

The USDA Civil Rights Action Team (CRAT) reported that "[p]articipation rates in ... programs of the former Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service, particularly commodity programs and disaster programs, were disproportionately low for all minorities." Civil Rights at the United States Department of Agriculture, A Report by the Civil Rights Action Team, February 1997, p. 21. The report further stated that "one farm advocate at the Halifax, NC, listening session stated that according to information he received through the Freedom of Information Act ...'when hearing officers rule for the agencies, they were competent [upheld] 98 percent of the time, but when they ruled for the farmer, these same hearing officers were incompetent [reversed] over 50 percent of the time.... This is indisputable evidence of bias and discrimination against a whole class of farmers....'" CRAT at 23-24. The report also found that loan processing times for black farmers were three times longer than for white farmers in southeastern states.

The USDA National Commission on Small Farms reported that "[t]he history of discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in services extended to [minority] farmers, ranchers, and small farmers, and to small forestry owners and operators, is well documented. Discrimination has been a contributing factor in the dramatic decline of Black farmers over the last several decades." A Time to Act, A Report of the USDA National Commission on Small Farms, January 1998, p. 40.

- USDA Has Only Paid 1 in 4 Dollars of the Settlement's Value to African American Family Farmers. USDA has responded to concerns about the low payout rate in the settlement by insincerely stating that it did not promise to pay farmers a specific amount. The Consent Decree between African American farmers and USDA was estimated to be worth $2.25 billion in payments to farmers, but USDA has only paid $650 million in cash payments to farmers. This $2.25 billion estimate appears in a declaration from the attorneys for the farmers, and is cited in the fairness opinion in which the Court approved the proposed settlement. (Pigford v. Glickman, 185 FRD 82, 95) Judge Friedman, in assessing the fairness of the settlement, referenced this value, stating, "under the terms of this Consent Decree, the USDA is obligated to pay billions of dollars to African American farmers who have suffered discrimination." (Id.) This statement clearly reflects the farmers' and the Court's understanding of USDA's promise. If USDA did not intend to fulfill this promise, it should have made a clear statement challenging this assessment at the time the Consent Decree was under consideration by the federal court, rather than five years after the settlement was reached and approved.

- African American Family Farmers in the Settlement Faced USDA Opposition in Accessing Vital Information that Could Have Proved Their Claims. Although USDA has turned attention to the private individuals and companies that were hired to run the settlement to justify the high rate of denials in the settlement, USDA's refusal to provide for access to data on "similarly situated white farmers" created an obstacle which contributed to farmers' disappointing approval rates. According to the Court approving the settlement, farmers in the class were supposed to receive a "virtually automatic cash payment of $50,000," with little or no documentation required, but only 60% of the farmers in the class received this payment. (See Pigford v. Glickman, 182 F.R.D. 82, 95 (D.D.C. 1999)) While arguing that African American farmers had to meet exacting standards in proving that they fared worse than specifically identified, similarly situated white farmers, USDA consistently denied access to its files that held this information, making it nearly impossible for most farmers to succeed in the settlement.

- USDA Challenged the Rulings of the Private Entities that Presided over the Settlement. Although USDA has recently claimed that the arbitrators and adjudicators that the Department hired to run the settlement were the only entities responsible for the low success rate of the farmers in the settlement, USDA filed numerous challenges seeking to overturn awards to farmers. In fact, USDA's actions prompted the Court to comment on the surprisingly large number of USDA objections to successful claims. USDA filed challenges to at least 686 farmers who were awarded compensation the settlement. Also, DOJ records show that they were paid at least $12 million by USDA to spend some 56,000 legal staff hours challenging farmers' claims after the settlement was reached.

- USDA Has Acknowledged that African American Family Farmers were Subject to Unfair Treatment in Loan and Subsidy Programs. USDA is disingenuously relying on the absence of an admission of guilt in the Consent Decree to explain its litigious stance in the settlement process. The fact is that USDA accepted financial responsibility for the damages caused by discrimination underlying the settlement and acknowledged publicly that African American farmers faced discrimination in USDA loan and subsidy programs. USDA's own Office of Inspector General and Civil Rights Action Team (CRAT) reports were cited by the Court in Pigford as proof of the underlying discrimination, "The reports of the Inspector General and the Civil Rights Action Team provide a persuasive indictment of the civil rights record of the USDA and the pervasive discrimination against African American farmers." (Pigford v. Glickman, 185 FRD 82, 103-4).

Over five years after reaching the agreement with USDA that ended the Pigford v. Veneman civil rights case, African American family farmers are still struggling within an inadequate settlement program:

- 8,600 of 22,000 farmers in the settlement received nothing;

- 64,000 farmers were turned away without the opportunity to even file a claim; and

- USDA denied farmers access to vital information that could have proved their claims.

These farmers deserve a meaningful remedy that provides an opportunity for all potential claimants to have their cases heard on the merits and allows for consideration of all USDA-held data that may help them prove their claims.

USDA's mishandling of subsidy and loan programs is the sole source of the underlying problem, and USDA is responsible for rectifying this wrong. The settlement has utterly failed to live up to its promise of resolving the problems caused by decades of USDA discrimination against African American farmers. The private companies and individuals that were hired to run the settlement had no hand in USDA's underlying wrongdoings, and they are accountable neither to the public nor to the African American family farmers involved. The Department of Justice, as USDA's legal representative, is required to act in USDA's interests. USDA must accept accountability for its actions, stop pointing fingers at other parties and remedy the problems with the settlement without further delay.

Testimonials

African American Farmers' Accounts of USDA Discrimination

CALVIN KING

USDA Refused to Even Provide Mr. King with an Application

Calvin King visited USDA's local Lunenburg County Farm Services Agency (FSA) office in Kenbridge, VA in January 1981 to apply for a loan to purchase 27 acres of timber land adjacent to the farm where his parents had been sharecroppers since the early 1900s. The FSA official refused to even provide King with an application, telling him that no funds were available for his loan. "It was common knowledge that certain white farmers got better treatment. Everyone knew that the white farmers were getting loans while [black farmers] weren't. They were not far from us, just down the road, and it was just generally known that they were getting money from [USDA] but we weren't," says King.

King Joins the Civil Rights Settlement and is Denied the "Automatic" Payment, Appeal Still Pending More Than Five Years Later

After learning of the Pigford v. Veneman class action settlement, King sought restitution by joining the settlement in June 1999. He was assigned to Track A, the "automatic" $50,000 track, but his claim was ultimately denied. USDA's refusal to provide King with an application became a major obstacle in his case. He was left with no record that he applied for a loan, "If they'd offered an application, at least they'd have something on file. When you buy a car or go for a job at least they give you an application to fill out."

USDA's practice of withholding information on similarly situated white farmers who received loans also became an insurmountable hurdle for King. USDA refused to provide any information to King, despite having the data within its own files. King attempted to navigate the maze of public documents to prove his case, but failed. King named two similarly situated white farmers in his claim, one of whom he was certain was receiving loans, and another whom he was reasonably sure received loans and owned a large farm several miles from his parents' farm. He later learned that one of the farmers was actually leasing the farm to a white neighbor who operated the next farm over and several other farms in the area, "Had I listed [the other farmer] I would've been ok, but since I named [the land owner], I got denied. That was a mistake I made with the name, and that resulted in the denial. It seemed logical at the time that I assumed [the landowner] was receiving the [USDA] loans. But it's hard to tell in this area where one farm begins and another ends or who is farming what or who owns what. There are no clear boundaries like in the suburbs."

Calvin went back to the Kenbridge, VA FSA office in May 2000 attempting to define the boundaries between the farms, and met with further obstruction. "I wanted to demonstrate to them that the two farm operations were connected just to show how I had gotten the name confused. In the process, the FSA office denied me some basic information that should've been released, such as whether or not the farms were connected, and how. And who was the farmer that farmed the land that year," says King. He explains, "It seems to me that they withheld information that they should not have withheld from me ... but I was not given anything." Ironically, says King, "the FSA office in Fredericksburg, VA ... provid[ed] me with information ... about two black farmers ... if the black farmers' information was released to me, the white farmers' information should have also been released."

In November 2000, King challenged the denial of his claim. Although his settlement claim was filed over five years ago, no decision has been made on his appeal, and Calvin's case remains unresolved today.

King Files New Complaint for Retaliation by USDA for his Participation in the Settlement

King faced retaliation due to his participation in the Pigford civil rights settlement, and filed a subsequent discrimination complaint with USDA. King explains, "I filed an additional complaint against USDA because of ongoing discrimination I experienced after the Pigford suit, and probably because of my involvement in the Pigford suit. After Pigford, I was continually discriminated against." King's experience is that "USDA is not applying the same standard to black farmers that it is applying to white farmers, and that constitutes an act of discrimination against me and all black farmers. USDA law is the same all over the country. The law is the law, and it should be applied equally throughout the land."

LINWOOD BROWN

USDA's Late Payments Caused Crop Yields to Dwindle

Linwood Brown sought assistance from the Farm Services Agency (FSA) in Brunswick County, VA, from 1980 through 1994. Brown's farm, at the time, consisted of about 80 acres, upon which he grew corn, soybeans and tobacco. Brown is the fifth generation to farm his land, which his relatives worked as slaves. "The old slave house is still here on the property," says Brown.

In Brown's experience in applying for USDA crop loans, USDA would withhold payments until it was too late to harvest the crops, creating a cycle that continually decreased the size of his yields, "I'd apply for assistance around the first of the year, but wouldn't receive the money until June or July. That wasn't enough time to plant the seeds, put the fertilizer and chemicals on at the right time, do all the things you needed to do. So then your yields would suffer, and you'd only get, say, 80% of your crop. Then they'd use that against you in future years saying your yields were low so you can't get the money you need to farm the land." Though he applied for assistance at the same time as area white farmers, Brown's checks would arrive months later, while his white counterparts received faster turnaround. Brown states, "it was a constant struggle for us."

In Brunswick County, African American farmers were required to report to a supervisor to obtain payments expense-by-expense while white farmers were paid in a lump sum. As Brown explains "the black farmers had a supervisor of their [FSA] bank account, where you had to take your bills and receipts to prove that you needed the money. You could only go to the supervisor's office on Wednesday. The white farmers just picked up their check and put it in their pocket, they had no supervision, no questions asked."

Civil Rights Settlement Failed to Provide Restitution

Linwood Brown was part of the Pigford v. Veneman lawsuit, but chose to opt out.

"That process left the burden on the farmer to prove his case. You had to have hard facts to prove you were discriminated against. I went through that and won a partial settlement. But it's not fully resolved. USDA was supposed to come back and pay for the other years that they discriminated against me, but that never took place." Linwood explains, "this same situation has happened to a lot of farmers. They [USDA] find discrimination but they won't pay. They'll fight each one to the end. They'll use taxpayer money to fight against you. The good old boy system is still in place, and working well."

Brown laments the land loss that has plagued African American farmers denied USDA loans and subsidies, "the saddest days of my life I spent watching USDA selling these people's farms. To see that, it was unexplainable. I went and saw some of the sales, when they auction off the black farms. USDA would literally sell the farm and leave the family sitting there under the tree, watching somebody move onto their farms they've been living and working on for generations, some since slavery. Now they don't have a place to call home. When you witness what they are doing here, it doesn't look like you live in America. You just won't believe that this kind of thing, this discrimination, is happening to poor struggling farmers here in America. But it has... it still is. It's still the same today."

LEON PULLEY

Local USDA Office Repeatedly Turned Away African American Farmer and Delayed Fulfillment of Loan

Leon Pulley owns a farm in Butler County, Missouri, where he has grown milo and soybeans for two decades. Between 1994 and 1996, USDA repeatedly delayed loan payments, severely limiting the profitability of his crops. "The way it usually works is that you would file for Farm Service Agency (FSA) assistance in February. You're supposed to get your money in March or April in order to have enough resources to plant on time to reach harvest before the fall rains and frost come. White farmers were getting their money on time, every time. But not the black farmers," says Pulley. USDA delayed payment until as late as September for several consecutive years.

Pulley also experienced obsfucation at the hands of local USDA FSA representatives, "You'd go in, they'd tell you they were busy, to come back later, and so you would come back later and they'd say the same thing again. I got told that every time," Pulley explained. Pulley believes these practices were only aimed at African American farmers, "They [FSA representatives] weren't letting some people get money at all, and others would get the money too late so they couldn't set up in time to harvest so got bad or no crops." Pulley knew of two or three white farmers in similar farm situations who got their money on time, and contends that discrimination is to blame for the disparity.

Pulley signed up for the class action lawsuit and was admitted to Track B. To his disappointment, his case was never heard. He says that his lawyers were inadequate and his case "just fell through the cracks."

Unfair Treatment by USDA Continues

Leon has continued to seek help through USDA programs. Last year, he was turned away and told there was no money. This year, he applied and was also rejected. Leon has reduced the amount of land he actively farms to 20 acres, and has put the remainder of his farm into the wetlands conservation program. Ever since 1996, he has been paying USDA $154 a month toward the debts he has accumulated over the years, debt which, ironically, was accrued largely due to USDA's unjust delays of his loans.

LEROY McCRAY

Rejected Twice by USDA, McCray Nearly Gave up on Farming Altogether

Leroy McCray applied to the Farm Services Agency (FSA) around 1990, requesting $5 million in working capital and equipment loans to set up a chicken farm in Sumter County, SC. The local USDA FSA official met with McCray, telling him that no money was available. "They told me to go look for a private loan," he recalls. This story was not what his white neighbors were told, "I knew there were 7-8 white farmers in my area with chicken farms who were getting the money, the same type of loan that I wanted. And they only had high school education and limited or no farming experience when they got their loans. I was a college graduate with lots of experience with different farm animals and operations, and I was getting denied. It didn't make any sense." USDA denials stifled McCray, "I never even got the chance to start the chicken farm like I wanted. I just gave up." Several years later, he applied for another loan, McCray says, "They didn't even take the application I had filled out because they just said there was no money available."

Settlement Presented Difficult Compromise

McCray learned of the civil rights settlement with USDA, and chose to pursue relief through Track A, though he felt that it would not make him whole. "It wasn't an easy decision, I didn't want to just take the $50,000. I wanted to go for the $5 million they had denied me, but it seemed like it would never be resolved if I did that." McCray is one of the few farmers who received relief under the settlement. Despite his success, McCray does not expect USDA's treatment of African American farmers to change. "It's not any better, it's still the same as it was. It's the same plot."

ALAN DIGGS

Local USDA Officials Used Common Tactic of Withholding Paperwork to Delay Loans

Alan Diggs and his brother Milton Diggs farm together as the Diggs Bros. Partnership in Southampton County, VA farm. Their story of discrimination is similar to many other African American farmers' accounts: complicated mountains of paperwork, processing delays, and late payments.

Diggs would witness his white neighbors being treated differently by USDA's local FSA officials. "The FSA officer would trickle the paperwork out one piece at a time to black farmers, there'd be 10-15 days in between communications, then another piece of paperwork would be in the mail, 3-4 days lag time, then you fill it out and keep coming back and then there's another paper to fill out. Another figure, another number they needed from you. White farmers were already getting their work done, they weren't getting the extra paperwork we did. They'd get a full package, fill it out, and in ten days to two weeks they'd have their money."

Diggs has survived in farming while many African American farmers have been forced out of farming, "We might be the only black farmers of size doing this any more, a lot of people have dropped out of farming because it's such a hassle, some of the white supervisors in the office try to make it hard. If USDA had made it easier for the black farmers, they might still be in business now. In a sense they just ran them out of business."

USDA Failed to Live up to Promises Made in Settlement

Alan Diggs received $50,000 in the Pigford settlement, but remains disappointed by the treatment he received from USDA throughout the process. Diggs explains, "When the settlement came out, USDA said you were entitled to $50K and they would write off all your debt. I got the $50K but they only wrote off a portion of the debt I owed. During the Monitor review, when I put in an appeal, they tried to tell me that the years that they did not write off were years I wasn't discriminated against. But that's not what they said they were going to do. They said they'd write off all your debt. But they didn't." Diggs believes that priorities shifted during the course of the settlement, "The Bush Administration put this thing on the back burner when they took office. When Bill Clinton was in office, it was a front burner issue. But that changed when Bush got in there."

About This Report

Authors:

Arianne Callender

Brendan DeMelle

Reviewers:

John Boyd, President, National Black Farmers Association

Richard Wiles, Senior VP, Environmental Working Group

Ken Cook, President, Environmental Working Group

This report is a joint project of the Environmental Working Group (EWG) and the National Black Farmers Association (NBFA). This project was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. We would also like to thank the Joyce Foundation for its continuing support of EWG's agricultural policy research. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and editors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters. EWG is responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation contained in this report.

Table: Farmers Seeking Entry Under Court-Mandated Extension - All 50 States

| State | Rejected | Granted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 14,268 | 294 | 14,562 |

| Alaska | 126 | 0 | 126 |

| Arizona | 75 | 0 | 75 |

| Arkansas | 1,430 | 70 | 1,500 |

| California | 1,495 | 30 | 1,525 |

| Colorado | 53 | 1 | 54 |

| Connecticut | 137 | 1 | 138 |

| Delaware | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| District Of Columbia | 72 | 7 | 79 |

| Florida | 908 | 34 | 942 |

| Georgia | 3,228 | 81 | 3,309 |

| Hawaii | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Idaho | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Illinois | 2,864 | 29 | 2,893 |

| Indiana | 350 | 1 | 351 |

| Iowa | 71 | 1 | 72 |

| Kansas | 125 | 1 | 126 |

| Kentucky | 77 | 3 | 80 |

| Louisiana | 2,312 | 21 | 2,333 |

| Maine | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maryland | 241 | 11 | 252 |

| Massachusetts | 84 | 2 | 86 |

| Michigan | 1,219 | 11 | 1,230 |

| Minnesota | 33 | 4 | 37 |

| Mississippi | 18,983 | 286 | 19,269 |

| Missouri | 299 | 2 | 301 |

| Montana | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nebraska | 33 | 0 | 33 |

| Nevada | 65 | 6 | 71 |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New Jersey | 389 | 6 | 395 |

| New Mexico | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| New York | 550 | 14 | 564 |

| North Carolina | 2,448 | 1,012 | 3,460 |

| North Dakota | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Ohio | 410 | 10 | 420 |

| Oklahoma | 3,309 | 51 | 3,360 |

| Oregon | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Outside U.S. | 74 | 1 | 75 |

| Pennsylvania | 133 | 4 | 137 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| South Carolina | 1,826 | 70 | 1,896 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tennessee | 4,642 | 24 | 4,666 |

| Texas | 853 | 21 | 874 |

| Utah | 28 | 0 | 28 |

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 252 | 18 | 270 |

| Washington | 25 | 2 | 27 |

| West Virginia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Wisconsin | 280 | 2 | 282 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

|

|||

| National Total | 63,816 | 2,131 | 65,947 |

Table: Nearly 9,000 Black farmers were denied "Automatic" payments by USDA — All 50 States

| State | Number Eligible |

Receiving "Automatic" Awards |

Denied "Automatic" Awards |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Receiving Awards | Percent Receiving Awards | Number Denied Awards | Percent Denied Awards | ||

| Alabama | 4,511 | 3,096 | 69% | 1,415 | 31% |

| Alaska | 2 | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Arizona | 6 | 2 | 33% | 4 | 67% |

| Arkansas | 1,986 | 1,293 | 65% | 693 | 35% |

| California | 232 | 127 | 55% | 105 | 45% |

| Colorado | 11 | 4 | 36% | 7 | 64% |

| Connecticut | 10 | 3 | 30% | 7 | 70% |

| Delaware | 3 | 2 | 67% | 1 | 33% |

| District Of Columbia | 26 | 13 | 50% | 13 | 50% |

| Florida | 472 | 248 | 53% | 224 | 48% |

| Georgia | 2,960 | 1,757 | 59% | 1,203 | 41% |

| Hawaii | 1 | 1 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Idaho | 1 | 1 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Illinois | 282 | 144 | 51% | 138 | 49% |

| Indiana | 39 | 13 | 33% | 26 | 67% |

| Iowa | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 100% |

| Kansas | 48 | 24 | 50% | 24 | 50% |

| Kentucky | 118 | 54 | 46% | 64 | 54% |

| Louisiana | 991 | 478 | 48% | 513 | 52% |

| Maine | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Maryland | 66 | 32 | 49% | 34 | 52% |

| Massachusetts | 6 | 3 | 50% | 3 | 50% |

| Michigan | 148 | 72 | 49% | 76 | 51% |

| Minnesota | 15 | 5 | 33% | 10 | 67% |

| Mississippi | 4,373 | 2,643 | 60% | 1,730 | 40% |

| Missouri | 147 | 80 | 54% | 67 | 46% |

| Montana | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Nebraska | 2 | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Nevada | 9 | 6 | 67% | 3 | 33% |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| New Jersey | 57 | 34 | 60% | 23 | 40% |

| New Mexico | 3 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 100% |

| New York | 58 | 33 | 57% | 25 | 43% |

| North Carolina | 1,989 | 910 | 46% | 1,079 | 54% |

| North Dakota | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Ohio | 42 | 20 | 48% | 22 | 52% |

| Oklahoma | 794 | 541 | 68% | 253 | 32% |

| Oregon | 1 | 1 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

| Outside U.S. | 36 | 26 | 72% | 10 | 28% |

| Pennsylvania | 22 | 13 | 59% | 9 | 41% |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| South Carolina | 1,274 | 793 | 62% | 481 | 38% |

| South Dakota | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Tennessee | 663 | 407 | 61% | 256 | 39% |

| Texas | 437 | 287 | 66% | 150 | 34% |

| Utah | 2 | 1 | 50% | 1 | 50% |

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Virginia | 292 | 146 | 50% | 146 | 50% |

| Washington | 6 | 4 | 67% | 2 | 33% |

| West Virginia | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

| Wisconsin | 25 | 13 | 52% | 12 | 48% |

| Wyoming | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 100% |

|

|

|||||

| National Total* | 22,181 | 13,411 | 61% | 8,770 | 40% |

* Note: Information in this table is based upon data received from the Office of the Monitor on 4/26/2004. The 7/12/2004 report from the Office of the Monitor states that the total number of awards received is now 13,429.