WASHINGTON – A new Environmental Working Group geospatial analysis finds over 2 percent of North Carolina’s 7,352 swine and poultry factory farms are in or just outside floodplains. When these farms flood, they can contaminate water with bacteria and other health hazards.

“The 156 factory farms we found in and near North Carolina’s floodplains are at a higher risk of flooding, posing a clear and present danger to the environment and public health,” said Al Rabine, EWG senior GIS analyst and co-author of the report. “But many more facilities are at a heightened danger of inundation, thanks to the climate crisis and outdated floodplain science.”

As the climate emergency intensifies, flooding from more frequent and more severe storms has already been seen in North Carolina, and more is expected.

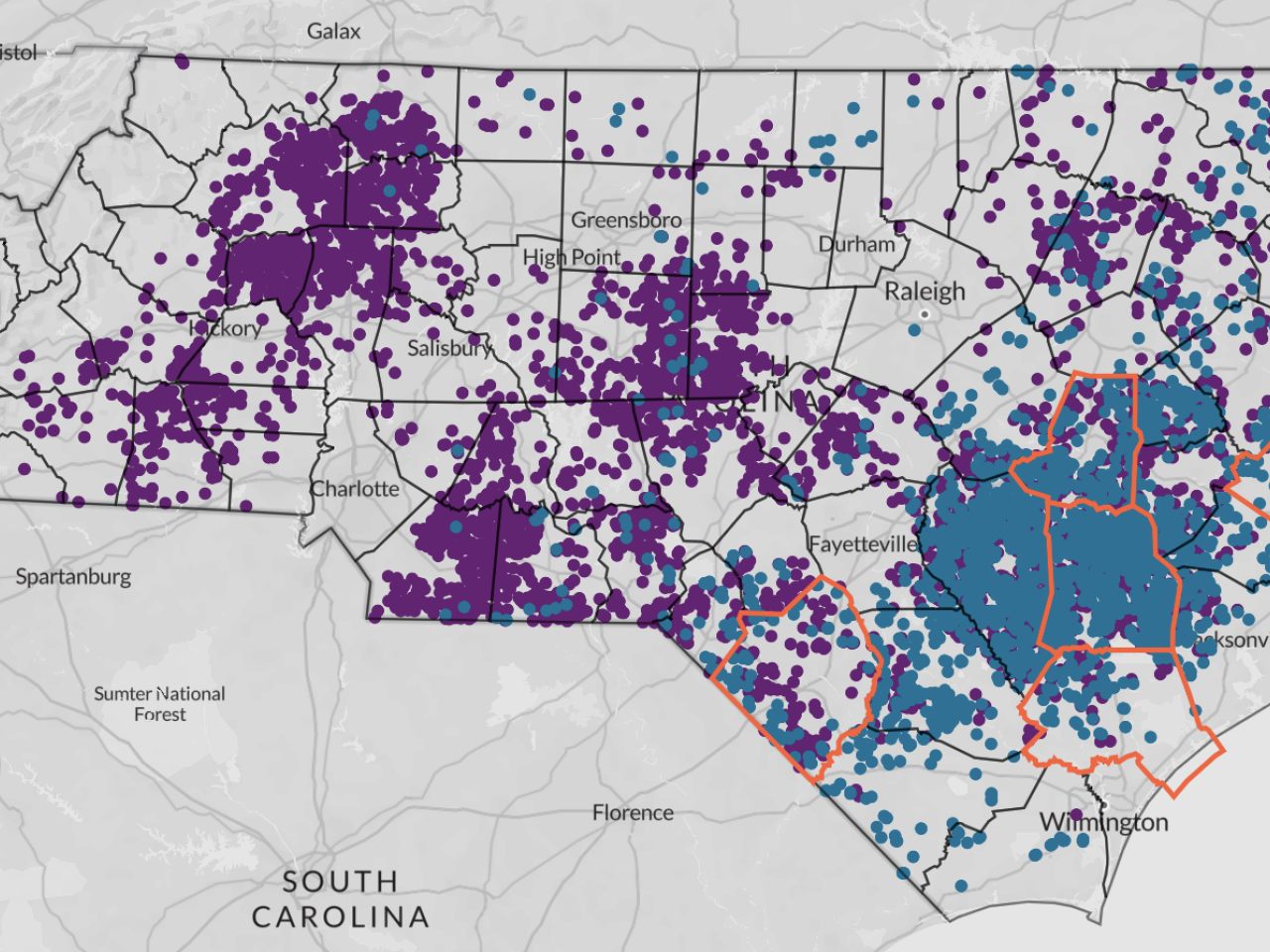

EWG researchers identified 156 concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in floodplains or within a 100-foot buffer of floodplains in North Carolina – 59 swine and 97 poultry facilities, representing more than 2 percent of the 7,352 CAFOs in the state.

The five North Carolina counties with the most floodplain CAFOs are Duplin, Wayne, Pender, Craven and Robeson. These counties are located in three different watersheds – meaning they’re in danger of flooding from disparate waterways and their tributaries.

To find these CAFOs, EWG’s geospatial experts combined data from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality with imagery from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, overlaying both with floodplain data from the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, which uses Federal Emergency Management Agency standards and practices.

Floodplains fall into two categories: a 100-year floodplain, with a 1 percent chance of flooding in a given year, or a 500-year floodplain, with a 0.2 percent chance of flooding. But in many places across the U.S., 100-year and even 500-year floodplains are now seeing flooding regularly. FEMA’s floodplain mapping process sometimes relies on old data that can miscalculate elevation and disregard small streams. It also uses previous events to predict future risk.

In total, EWG has geolocated 2,489 swine operations raising about 8.8 million pigs and 4,863 poultry operations housing about 544 million chickens and turkeys in North Carolina. The organization has been tracking CAFOs in the state since 2016, and the new map is based on this prior work, conducted in partnership with the Waterkeeper Alliance.

CAFOs generate extraordinary amounts of excrement and urine, which are loaded with chemicals like nitrogen and phosphorus. This waste is stored on site, typically open to the elements, before it’s applied, untreated, to nearby farm fields as a crop fertilizer.

When CAFOs flood, the manure they produce and store on-site can wash into nearby creeks and rivers, carrying with them antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pathogens like E. coli, Giardia and salmonella. Such pollution can last for months after a major flooding event.

Even when applied correctly or in areas that are not floodplains, animal manure can pollute waterways, feeding toxic algae blooms and contaminating private wells.

On swine CAFOs, manure and urine are piped into open-air cesspools the industry calls “manure lagoons” containing millions of gallons of liquid with dirt walls prone to leaks, breaches and spills.

On poultry CAFOs, chicken or turkey feces are shoveled into enormous putrid piles with bird carcasses, feathers and bedding referred to as “litter” and often left uncovered.

Dozens of swine CAFOs in floodplains have permanently closed since 1999 by taking advantage of a North Carolina buyout program. But EWG found 59 CAFOs still located in these higher-risk areas. The state’s program is chronically underfunded or not funded at all. There is no state buyout program for poultry facilities in floodplains.

“EWG’s analysis underscores the need for more accurate understanding of the risk posed by North Carolina’s CAFOs – and how flooding compounds it,” Rabine said. “The state must do more to protect its people and the environment from the dangers of CAFOs.”

EWG recently joined a coalition, led by Earthjustice, of 51 citizen groups, environmental nonprofits and community advocacy organizations petitioning the Environmental Protection Agency to improve its oversight of water pollution from CAFOs.

###

The Environmental Working Group is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization that empowers people to live healthier lives in a healthier environment. Through research, advocacy and unique education tools, EWG drives consumer choice and civic action. Visit www.ewg.org for more information

.jpg?h=827069f2&itok=jxjHWjz5)