Nitrate contamination of drinking water is getting worse in much of rural Minnesota, an Environmental Working Group analysis of state data found.

Between 1995 and 2018, tests detected elevated levels of the toxic chemical in the tap water supplies of 115 Minnesota community water systems.1 In that period, nitrate levels rose in almost two-thirds of those systems – 72 communities, or about 63 percent. Those water systems serve more than 218,000 Minnesotans, mostly in farming areas in the southeast, southwest and central parts of the state.

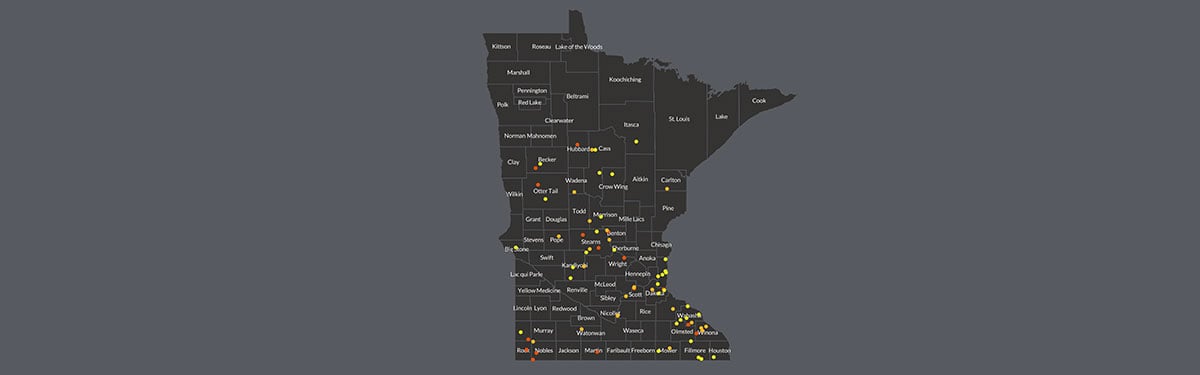

EWG’s interactive map shows where nitrate contamination rose during the study period, based on Minnesota Department of Health data obtained under the state’s public records law.

Minnesota Communities With Increases in Nitrate Contamination of Drinking Water Supplies, 1995 to 2018

EWG’s analysis underscores what we reported in a study and map issued in January 2020. The earlier analysis found that in 95 mostly rural Minnesota communities that draw their drinking water from groundwater, elevated nitrate levels were detected at least once since 2009. Our new analysis looked at communities that use either surface water or groundwater and tracked trends over 24 years.

Health Hazards of Nitrate

Nitrate is a primary chemical component of fertilizer and manure that can run off farm fields and seep into drinking water supplies. Under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, the legal limit for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams per liter, or mg/L. This limit was set in 1962 to guard against so-called blue baby syndrome, a potentially fatal condition that starves infants of oxygen if they ingest too much nitrate.

But newer research indicates that drinking water with 5 mg/L nitrate or even lower is associated with higher risks of colorectal cancer and adverse birth outcomes, such as neural tube birth defects. And the Minnesota Department of Health says a level of 3 mg/L indicates that “human-made sources of nitrate have contaminated the water and the level could increase over time.”

We analyzed data on all 115 community water systems that had at least one test at or above 3 mg/L. More than a third of those communities showed decreasing nitrate levels. However, it is clear that in most places with the most serious contamination, the problem is getting worse. Of the community water systems where nitrate exceeded the federal legal limit, fully 67 percent, serving about 48,500 Minnesotans, showed increased contamination over the study period.

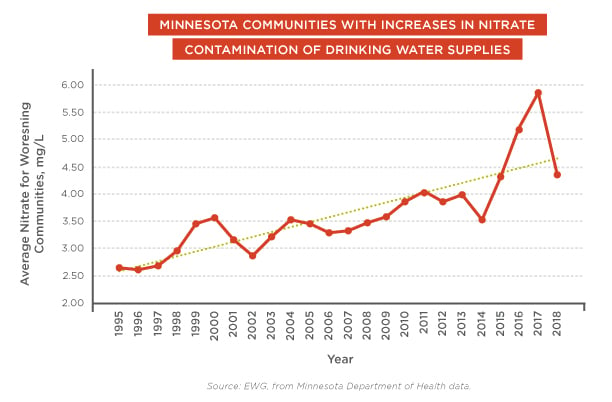

For the 72 communities we analyzed where contamination rose, average nitrate contamination of drinking water jumped by 61 percent between 1995 and 2018. In 1995, average contamination was 2.7 mg/L. By 2009, average contamination had increased to 3.6 mg/L and continued climbing to 4.4 mg/L in 2018.

Figure 1. Average Nitrate Levels in Minnesota Communities Where Contamination Rose, 1995 to 2018

Spikes in nitrate contamination in two smaller systems in southern Minnesota drove the sharp increase in average contamination in 2016 and 2017 (Figure 1). Both systems draw their drinking water from surface water.

- In the Rock County Rural Water District, serving 2,256 people, the average levels of nitrate contamination jumped from 1.6 mg/L in 2015 to 9.5 mg/L in 2016 and peaked at 15.2 mg/L in 2017 before falling to 6.6 mg/L in 2018, still much higher than in 2015. (See Case Studies.)

- In the City of Fairmont water system, serving more than 10,000 people in Martin County, average nitrate contamination increased from 0.2 in 2015 to 7.2 mg/L in 2016 reached 4.3 mg/L in 2017 and fell to 2.9 mg/L in 2018.

Who Is Affected?

Agriculture pollution often disproportionately affects low-income rural Americans who cannot afford to buy bottled water or install effective but expensive in-home filter systems. Of the 72 Minnesota systems we analyzed, 61 percent were in a U.S. Census block group with median household income below the state’s average. Installation of expensive treatment technologies to reduce nitrate levels can be a struggle in these communities. (See Case Studies.)

The type of test data available for community water systems is not available for private wells. It is likely that nitrate contamination has also increased over time in the thousands of private wells in the state, since many draw water from the same groundwater sources as community water systems. EWG’s earlier report found that between 2009 and 2018, more than 3,300 private wells in the state had nitrate levels at or above the federal legal limit of 10 mg/L.

Case Studies

Hastings

The town of Hastings is named after Minnesota’s first elected governor. It sits at the confluence of the Mississippi and Vermillion rivers in the southeast corner of the state. The Hastings community water system serves 22,335 residents.

In 2015, the Pioneer Press of St. Paul reported that about a decade earlier, “Hastings saw nitrate levels in its groundwater rise toward unsafe levels. City officials believed farm runoff, likely delivered to the aquifer by the Vermillion River that cuts through miles of farmland, was to blame.”

The newspaper reported that in 2008, the city spent $3.5 million on a new water treatment plant to lower nitrate levels, at an estimated cost of $410 per household. EWG’s research found that average nitrate contamination leveled off at around 6.4 mg/L after 2008, still an increase of 93 percent between 1995 and 2018.

In 2019, Hastings Public Works Director Nick Egger told the Minneapolis Star Tribune that since he has no authority over agriculture operations and their pollution, his only option other than spending taxpayer funds on cleanup is to “ask politely” for farmers to control dangerous chemicals running off crop fields.

Adrian

The community water system in Adrian, in the southwest corner of the state, serves 1,211 people from groundwater wells. In 2015, town leaders were forced to shut down a water treatment plant and issue vouchers for free bottled water, after nitrate levels were declared unhealthy for infants and pregnant women. EWG found that Adrian’s average nitrate contamination increased by 96 percent between 1995 and 2018.

Adrian’s 2015 water system shutdown was the second such incident since the town bought a nitrate removal system, in 1998. The town’s deputy clerk-treasurer, Rita Boljes, told the Star Tribune that treating the water for nitrate is now Adrian’s largest non-salary expenditure.

“It’s just part of living in Adrian,” she said.

Rock County Rural Water System

Rock County, in Minnesota’s farthest southwest corner, houses the historic Blue Mounds State Park and is home to the geographically unique Sioux Quartzite bedrock and a large bison herd. The Rock County Rural Water System serves 2,256 people. EWG calculated that the water system’s average nitrate concentration increased by a staggering 890 percent from 1995 to 2018.

After years of increasing nitrate levels in the system’s wells, in 2016 the water district board created a cost-share program that pays farmers to implement agricultural conservation practices in areas near well heads. It remains to be seen how effective this approach will be.

Conclusion and Outlook

It is clear that Minnesota’s community water systems have a worsening nitrate contamination problem. Nitrate in Minnesota’s drinking water threatens the health and the pocketbooks of citizens who have done nothing to contribute to the problem. For nearly 30 years, the state has had voluntary programs in place to address the massive quantities of nitrates from agriculture. But as this report clearly shows, during that time the majority of the community water systems most contaminated with nitrate have continued to get worse.

In January 2020, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture began implementing its new nitrate groundwater protection rule. However, the rule fails to provide the same protections to private well owners that it provides to people getting drinking water from community water systems. And the minimal additional protections for community water systems that are contemplated under the new rule are largely uncertain.

For example, the new rule includes an unclear and unnecessarily drawn-out timeline for requiring farmers growing crops near public wells to take any additional steps to reduce their nitrate pollution. Instead of requiring immediate action to determine excess commercial fertilizer application and mandating reduction, the new rule gives farmers more time to continue the same practices that have failed to improve water quality over the past 30 years.

Although the new rule is a laudable first step, more is undoubtedly needed to protect Minnesotans already drinking contaminated water and to ensure that all Minnesotans are protected from additional harm to their health.

To see the methods of this study, click here.

Notes

1 Water systems are public water supplies that serve residents in cities and towns year-round.