In almost all of Minnesota’s farm counties, the combination of manure plus commercial fertilizer is likely to load too much nitrogen or phosphorus or both onto crop fields, threatening drinking water and fouling the state’s iconic lakes and rivers, according to an Environmental Working Group investigation.

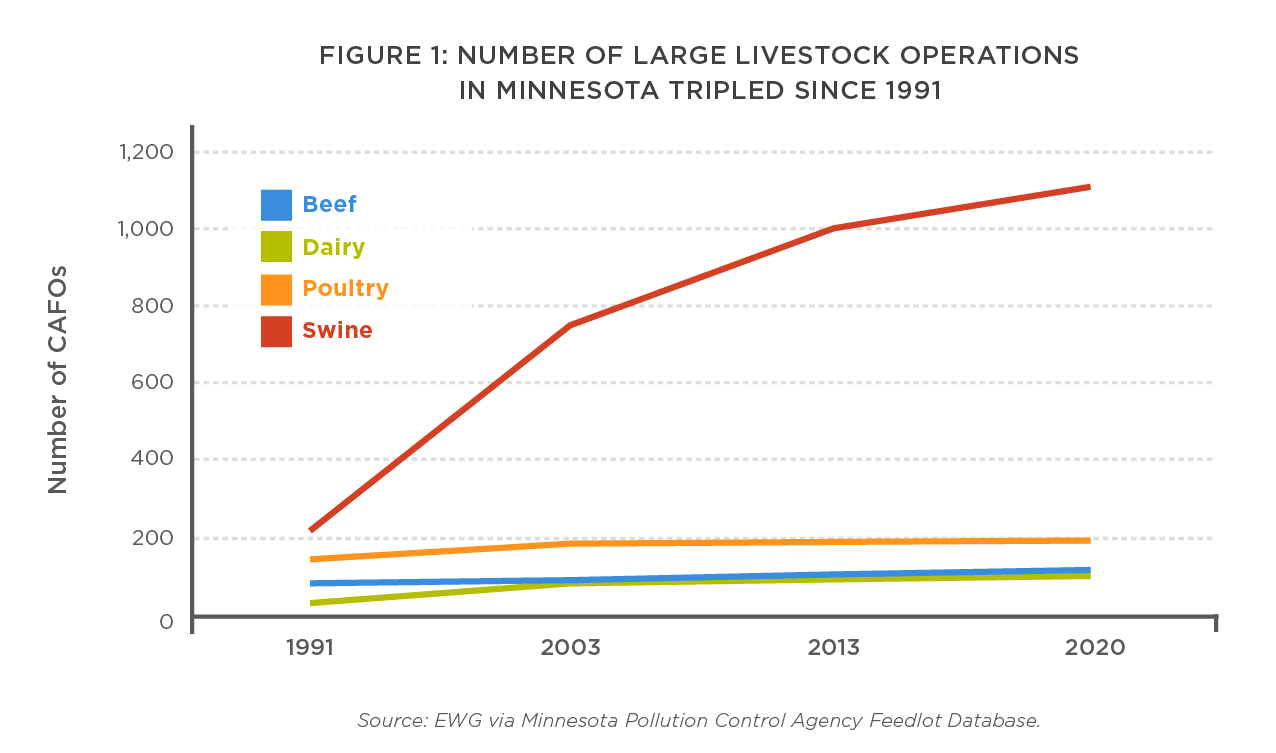

The problem arises from the extraordinary expansion and intensification of both livestock and crop production in the state. Since 1991, the number of large concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in Minnesota has tripled. At the same time, fertilizer sales have increased by more than a third, fueled by the nearly 1.5 million additional acres devoted to corn.

Every year, feedlots of all sizes in the state produce nearly 50 million tons of manure – rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, the same chemicals in the more than three million tons of commercial fertilizer applied annually. Nitrogen and phosphorus are essential crop nutrients, but when they run off the fields, they can pollute drinking water sources and other bodies of water.

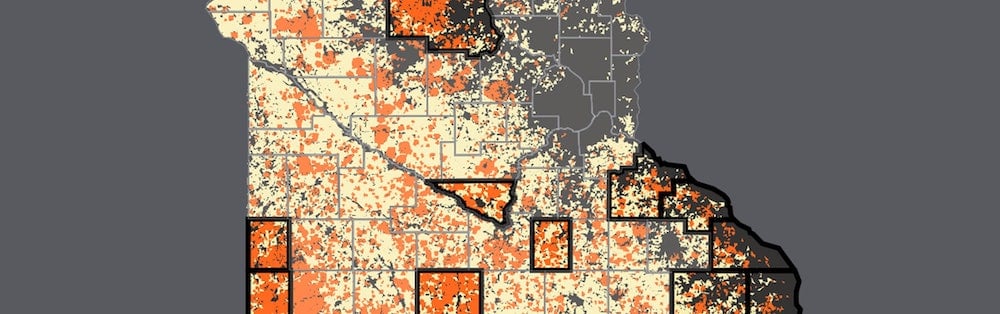

Using advanced geospatial techniques, EWG simulated and mapped every crop field across Minnesota likely to receive manure from nearby cattle, hog or poultry feedlots, to estimate the amount of manure applied in each county. We then added those amounts to the nitrogen and phosphorus in the fertilizer sold in the county.

The results are bad news for the state’s water quality.

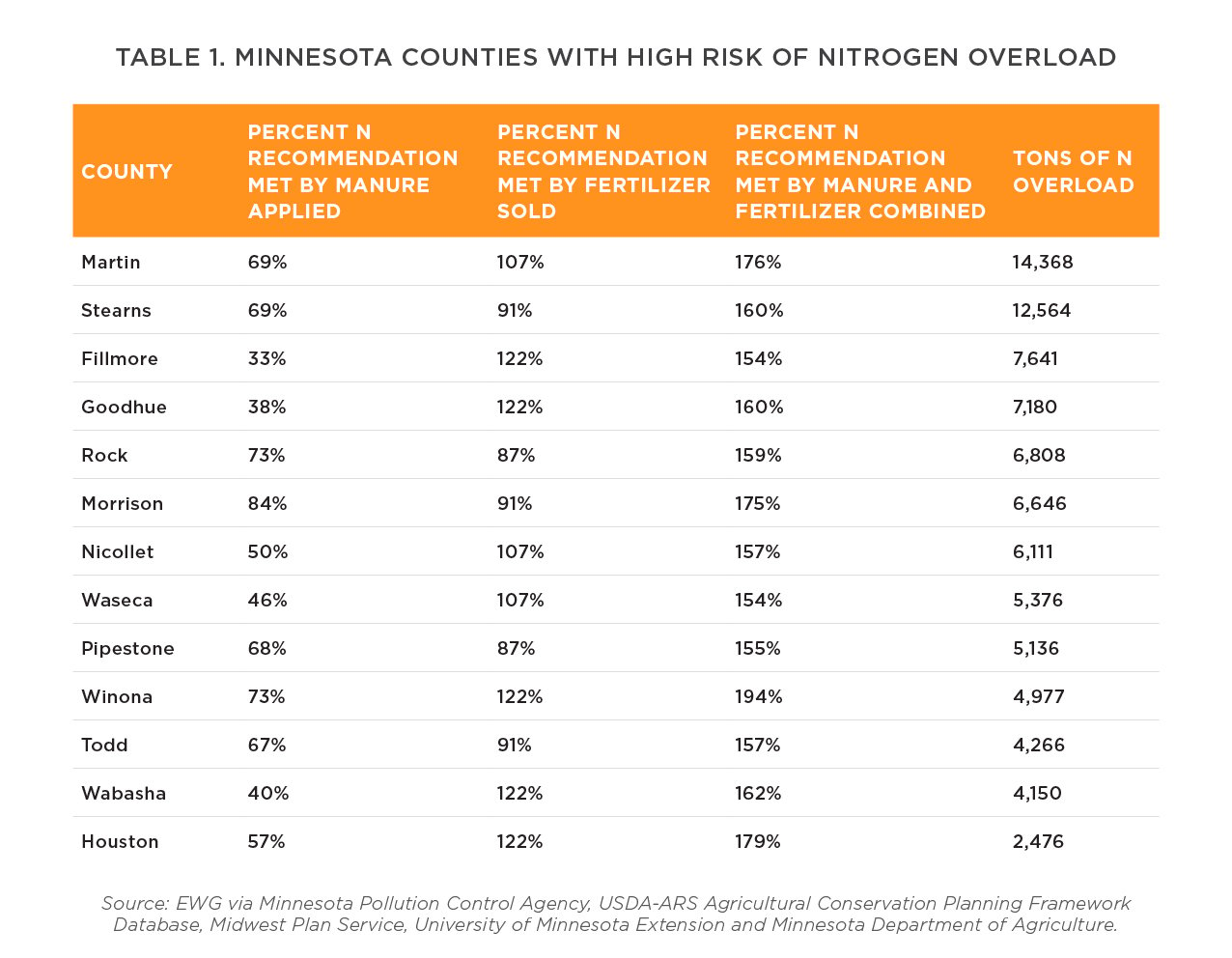

- In 69 of Minnesota’s 72 agricultural counties, nitrogen from manure combined with nitrogen in fertilizer exceeded the recommendations of the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, or MPCA, and the University of Minnesota. In 13 counties, nitrogen from the two sources surpassed the recommendations by more than half. (Table 1.) This excess nitrogen is the major cause of nitrate pollution in drinking water, which is linked to elevated rates of cancer.

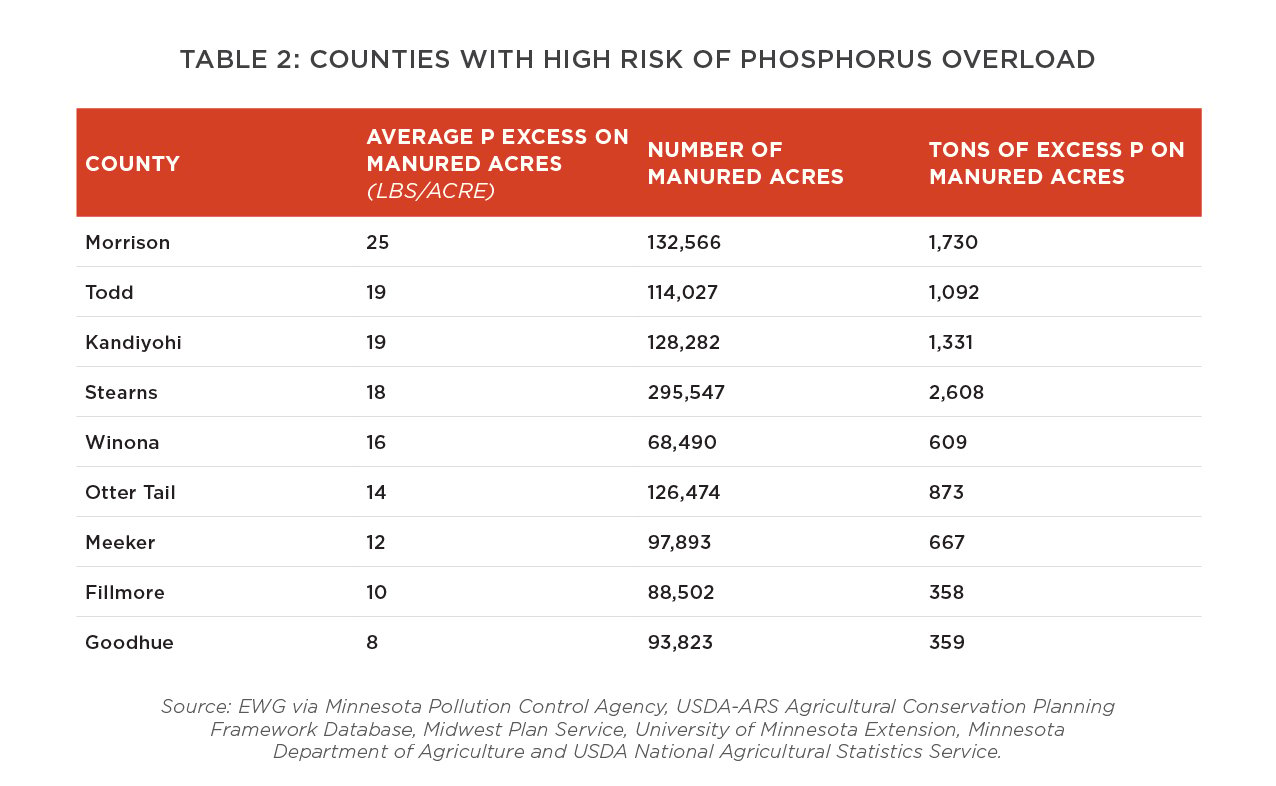

- In nine counties, phosphorus pollution from manure is of high concern. These nine counties account for over half of the nearly 1.5 million acres where application of manure adds at least 10 pounds per acre more phosphorus than needed by crops. (Table 2.) Four of those counties are also among the 13 with the most excess nitrogen. Phosphorus pollution of lakes and rivers can trigger algae blooms, which are not only ugly but can also produce toxic bacteria harmful to human and animal health.

Water Pollution Is Increasing

The statewide overload of nitrogen and phosphorus is taking its toll.

- An earlier EWG investigation found that 63 percent of Minnesota public water utilities with elevated levels of nitrate saw worsening contamination between 1995 and 2018.

- In the Sauk River watershed, the MPCA has listed nine lakes and four stream reaches as “impaired” because of bacteria, excess nutrients – mainly phosphorus – and algae blooms.

- After assessing all of the state’s major watersheds, the MPCA estimates that 56 percent of surface waters do not meet basic water quality standards, and that non-point source pollution, such as that from crop and livestock production, contributes to 85 percent of the state’s water pollution.

Since 1991, the number of large CAFOs in Minnesota has swelled from 468 operations to 1,497. (Figure 1.) Of the new operations, 86 percent were for feeding hogs, although the number for all other animals also grew. These operations are also getting bigger: Eight of the 67 dairy CAFOs built since 1991 house more than 8,000 cows, compared to just one of that size in 1991.

This extraordinary expansion raises concerns about the environmentally safe disposal of manure. Large CAFOS are just 4 percent of feeding operations in the state, but they produce nearly a third of the manure. Medium-size feedlots are 18 percent of all operations and contribute another 43 percent of the manure that goes on Minnesota fields every year.

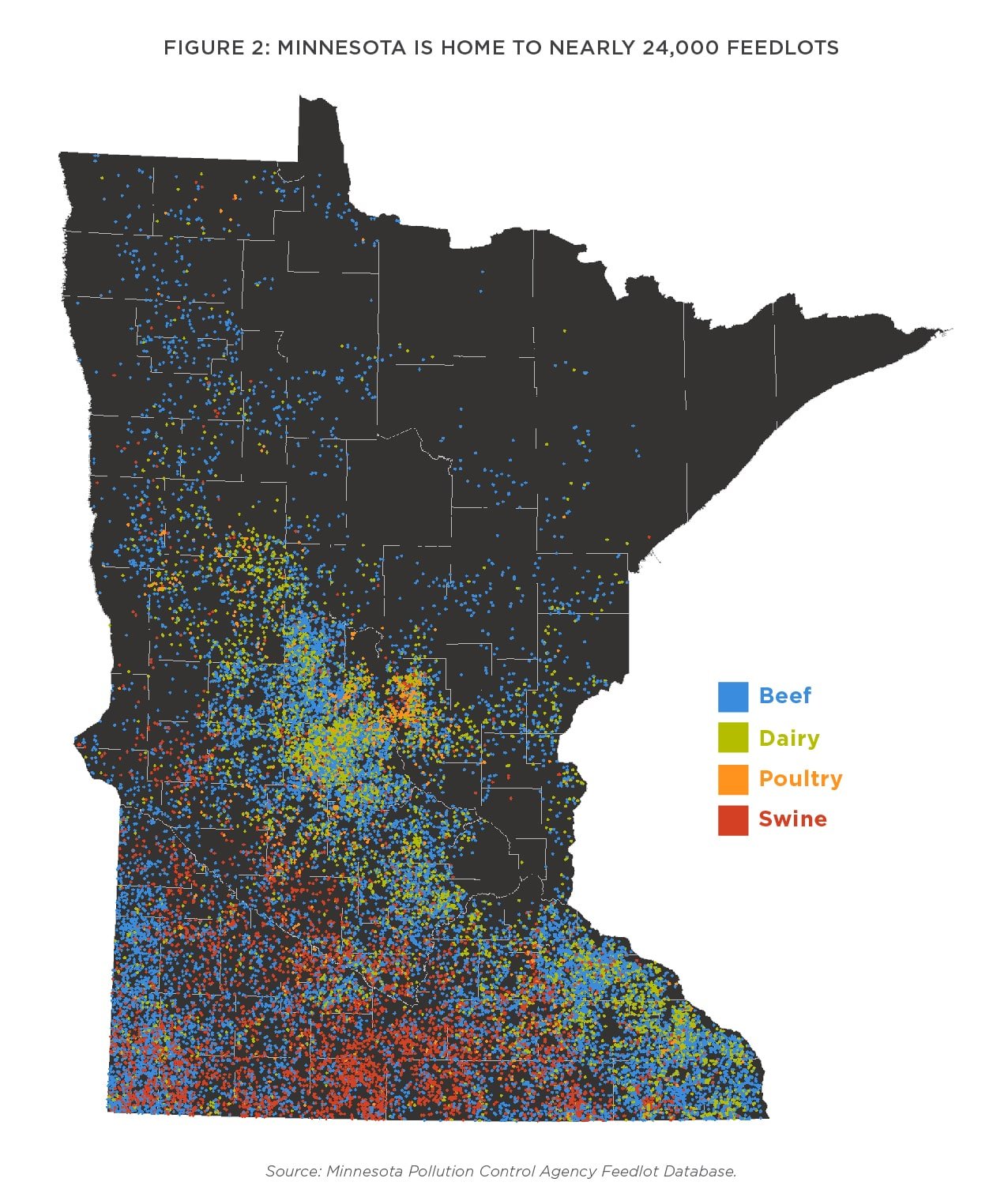

Today Minnesota has 23,725 feedlots of all sizes. Packed into counties in southern and central Minnesota, these operations house up to 1.2 million dairy cows, 1.6 million beef cows, 10.9 million hogs, and 66 million turkeys and chickens. These feedlots produce an estimated 49 million tons of manure annually – the equivalent of the waste from 95 million people, 17 times the state’s human population.

EWG simulated which individual fields could safely accept manure, based on distance from the feedlot and the amount of nitrogen recommended for growing crops. Nitrogen rates were based on MPCA guidelines and University of Minnesota fertilizer recommendations.

Figure 3: How Manure Moves From Feedlots to Fields

Source: EWG via Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, USDA-ARS Agricultural Conservation Planning Framework Database, Midwest Plan Service, University of Minnesota Extension and Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

In areas with a dense concentration of livestock, nearly every single crop field is needed if all the manure produced by nearby feedlots is to be used safely, without overloading nitrogen. In a few isolated areas, there is simply too much manure to dispose of within a reasonable distance. EWG’s simulation likely understates the risk of this overload, because we assumed every field within 5 miles of a cattle or hog feedlot and 25 miles of a poultry feedlot was available to take manure.

Moreover, research shows that much of the nitrogen considered lost to the atmosphere during manure storage and application ends up redeposited on the land nearby, adding to the potential overload.

The concentration of feedlots leaves little or no room to adapt to year-to-year changes in cropping patterns and fluctuating manure composition. It also increases the risk of overloading fields with phosphorus.

Manure Is Only Half the Story

You might expect fertilizer sales to be low in counties with dense concentrations of livestock, where manure alone can take care of the need for nitrogen fertilizer. Instead, we found little relationship between manure produced and fertilizer sold. Table 1 above lists 13 counties that are hot spots for nitrogen overload, where nitrogen from manure combined with nitrogen in fertilizer sold in the county exceeded crop recommendations by more than 50 percent.

Fertilizer sold in a county does not necessarily mean it was used there: A county might have half a neighboring county’s crop acreage yet sell twice as much fertilizer. To account for this, we grouped fertilizer sales for counties within Minnesota’s major crop regions, then allotted this regional sales data to counties based on fertilizer needs.

The interactive map below shows areas with an overload of nitrogen, as identified by our simulation.

It’s not surprising that the counties we identified are dealing with nitrate overload issues. Southwest Minnesota has struggled with nitrate-contaminated water for decades. In 2014, the MPCA declared that most bodies of water in the area did not meet standards for supporting aquatic life and recreation, and the town of Adrian has been forced to shut down a water treatment plant after nitrate levels exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limits. In Minnesota’s farthest southwest corner, Rock County’s water system’s average nitrate concentration increased by a staggering 890 percent from 1995 to 2018, according to EWG calculations.

Most of the CAFO growth in the state has been in Martin County, in south central Minnesota, home to 15 lakes on Minnesota’s 2020 list of nutrient-impaired water bodies. The list includes Budd Lake, which serves as the drinking water source for the town of Fairmont.

In townships in Morrison and Winona counties, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture found that more than 40 percent of private wells sampled had nitrate levels above the federal health limit of 10 micrograms per cubic liter. Many high-risk counties are located in vulnerable areas of the state, where karst bedrock or sandy soils make it easy for pollutants to reach groundwater.

The Phosphorus Problem

An inherent problem with manure is the imbalance between nitrogen and phosphorus relative to crop needs. When manure is applied to meet the nitrogen recommendation for crops, phosphorus is often overapplied. This nutrient imbalance is worse for poultry and cattle manure. The University of Minnesota Extension states that when turkey manure is applied to meet the nitrogen recommendation for corn, the crop gets more than five times the phosphorus needed.

Applying more phosphorus than the growing crop needs can lead to a buildup in the soil and greatly increases the risk of pollution. This risk is elevated in steep fields or those closer to lakes and streams. Long-term research in South Dakota showed that cattle manure applied to meet the nitrogen recommendation of crops dramatically increased soil phosphorus levels in less than 10 years. Eight pounds an acre of excess phosphorus can increase the level of phosphorus in the soil by 1 part per million, or ppm, which can quickly create problems for fields receiving manure year after year.

In Minnesota, soil phosphorus levels above 150 ppm (or 75 ppm near bodies of water) triggers action that requires farmers to lower the phosphorus levels from manure application. Other states, such as Indiana, have set this level even lower, suggesting that soil phosphorus is a concern once levels pass 50 ppm.

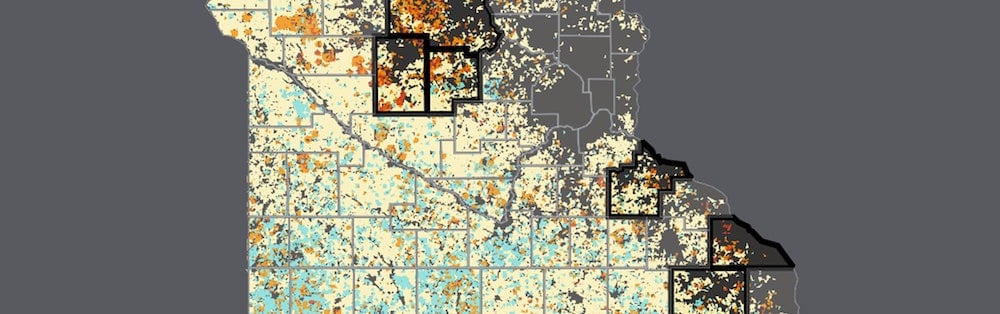

Our simulation found that on over 2.6 million Minnesota crop acres, or 57 percent of fields that received manure, more phosphorus was applied than removed. On nearly 1.5 million acres, this excess was more than 10 pounds per acre. On 590,000 acres, or 14 percent of manured fields, the excess was more than 25 pounds an acre.

Of the manured fields with a phosphorus excess greater than 10 pounds an acre, more than half fell in nine counties, as shown in Table 2, above. All nine counties are located in central and southeast Minnesota, and all have high densities of poultry and dairy operations.

In four counties – Morrison, Stearns, Todd and Winona – phosphorus from manure alone exceeds total crop requirements. Compounding the problem are the tons of additional phosphorus fertilizer sold in these same counties. Manure plus fertilizer phosphorus exceeds crop requirements in all but one of the counties in Table 2 (Otter Tail) and ranged from 90 percent to just over twice the phosphorus needed for the crop.

To limit phosphorus pollution from manure, farmers should apply manure to meet the phosphorus, not nitrogen, requirements of the crop. But because manure has much more nitrogen than phosphorus, far more acres are needed to apply manure at the proper rate for phosphorus. This can be twice as many acres needed for swine, compared to five times as many acres for turkey manure. In areas already saturated with manure, it is unlikely that this additional land is available.

Phosphorus pollution is the primary driver of algae growth in lakes. In the Sauk River watershed, in the heart of central Minnesota, the MPCA has set a Total Maximum Daily Load, or TMDL, to address bacteria, excess nutrients (mainly phosphorus) and nuisance algae blooms. Lake Osakis, a well-visited recreation area in the Sauk River watershed, was identified as a priority lake for water quality improvements.

Algae blooms are not only unsightly, they also have the potential to produce toxic cyanobacteria that are harmful to both human and animal health. Not far from Lake Osakis, in 2015 a child swimming in Lake Henry was hospitalized after exposure to blue-green algae. This followed the death of two dogs exposed to blue-green algae in nearby Red Rock Lake.

These examples are in central Minnesota, but algae blooms are common across all areas of the state with dense concentrations of cropland and livestock. The interactive map below shows the areas our simulation identified as having an overload of phosphorus.

Manure Overload and Public Health

Contamination of water resources poses a real threat to Minnesota drinking water and public health. Growth and consolidation of animal agriculture intensifies this threat. Accurately crediting the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in manure before any fertilizer is applied will improve soil health, protect drinking water and improve Minnesota’s lakes, rivers and streams while saving farmers millions of dollars in reduced commercial fertilizer costs. The data strongly suggest, however, that isn’t happening – especially in areas with dense concentrations of livestock.

A Minnesota Department of Agriculture survey revealed that almost three-fourths of farmers did not know how much nitrogen their manure contained, a basic requirement for good manure and fertilizer management. The same survey showed that almost two-thirds of farmers apply manure in the fall, a practice that increases the risk of nitrogen and phosphorus loss from manured fields, especially for liquid manure produced by hog and large dairy operations. Meanwhile, conservation practices that could reduce pollution from manure, such as cover crops, are drastically underused.

A comprehensive assessment of the capacity of Minnesota’s landscape to handle its manure and fertilizer load is essential to ensure current and future residents have clean water. That assessment must drive decisions about where to site new or expanded feedlots and set standards for fertilizer and manure management, especially in areas with dense livestock.

For methods and detailed results, click here.