Methods and Results: EWG and ELPC Analysis of AFOs in Maumee River Basin

TUESDAY, APRIL 9, 2019

By Sarah Porter, Senior Geospatial Analyst and Project Manager

Special thanks to Stuart Flack, Lucas Stephens and Madeline Fleisher with the Environmental Law & Policy Center and Sandy Bihn with Lake Erie Waterkeeper

Harmful algae blooms in Lake Erie began showing up in the mid-1990s and have increased in severity over time (D’Anglada et al., 2018). These blooms are caused by excess phosphorus, primarily dissolved phosphorus, which is delivered to the lake from upstream tributary watersheds. Nonpoint agricultural release is recognized to be the single largest source of excess phosphorus to western Lake Erie (IJC, 2018), with the two primary sources from agriculture being the application of commercial fertilizer and manure.

The Maumee River watershed basin has been identified as the largest contributor of phosphorus to Lake Erie, delivering an estimated 30 percent of total phosphorus coming to the lake from the U.S. and Canada (Maccoux, 2018). Commercial fertilizer has been the primary focus of research in the region.

The International Joint Commission (2018) estimates that 80 percent of agricultural phosphorus generated in the Western Lake Erie Basin, or WLEB, derives from commercial fertilizer, whereas approximately 20 percent derives from manure from animal feeding operations (AFOs) (IJC, 2018). Although trends point to decreasing commercial fertilizer application in the WLEB since the 1990s, dissolved phosphorus loads to the lake continue to rise, and blooms continue to increase in severity. Legacy phosphorus in the soil, tile drainage and tillage practices are leading current hypotheses to explain these increasing dissolved phosphorus loads (EPA, 2010).

Manure application from AFOs is assumed to have remained constant over time (IJC, 2018). This is mainly due to a lack of reliable, publicly available information about where and how many of these facilities exist, and the amount of manure and phosphorus they produce.

Animal operations above a certain size threshold are subject to regulation by government agencies. Many AFOs are below this threshold, however, and therefore do not need to apply for a permit that would provide more detailed information about the location, number of animals and other data. As a result, academics and agency officials have had little detailed information about the scope of livestock production in the watershed.

In addition, regulations vary by state, making consolidation of data across state lines challenging. The purpose of this study is to use remote sensing to map all AFOs in the Maumee River basin between 2005 and 2018. In addition, we estimate the number of animals housed at these facilities and the amount of manure and phosphorus they produce. It is our hope that this information will enhance our understanding of the role that AFOs play in the generation of phosphorus in the Maumee River Basin.

METHODS

Locating Animal Feeding Operations

National Agriculture Imagery Program, or NAIP, aerial photography was used to visually locate AFOs in the Maumee Basin. Consistent imagery was available across the study area beginning in 2005, the base year for this study. Due to alternating years of NAIP image collection after 2005, AFOs were categorized into the following periods for time of construction:

- Present in 2005.

- 2005 to 2010.

- 2010 to 2015.

- 2015 to 2018.

To capture very recent AFO construction (late 2018 to January 2019), Planet satellite imagery was used to supplement aerial photography. Several attributes were recorded for each facility, including the number of barns and their total square footage (as calculated by Environmental Law Policy Center), animal type (poultry, swine, beef cattle or dairy cattle) and the year of expansion, if any.

Animal type was assigned to each facility using the best judgment of the geographic information system, or GIS, analyst, based on a number of attributes unique to each facility, including the size and shape of each barn, the presence and number of feed bins, the location of fans, and the presence of lagoons and of visually identifiable animals.

We assigned animal type using permit data when available for a facility. We also used Google Street View, and separate reviewers performed several rounds of quality control. Despite this intensive process, visual assignment proved challenging in some cases, and there may be instances of misidentification in our analysis. In addition, we removed facilities from analysis if they appeared to be abandoned, as evidenced by dilapidated roofs or removal of infrastructure.

Permit Data

We obtained state permit data for facilities in the Maumee Basin from the following sources:

- Ohio: 2018 data (CAFF and NPDES permits, received March 19, 2019), obtained from the Ohio Department of Agriculture in spreadsheet form, with location information for each facility. Locations were geolocated to the nearest mapped facility.

- Michigan: 2018 data (NPDES permits) obtained from the MIWaters website. Permit data were matched from the interactive website to mapped facilities.

- Indiana: 2018 data (CFO permits, received Oc. 31, 2018) obtained from the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, or IDEM. Data were provided at a township scale. Where possible, permit data were matched to mapped facilities. This occurred when a single facility was permitted in a township and only one facility of the same animal type was mapped in that township. As this could not be performed for all facilities in Indiana, the permit status for all facilities in Indiana was considered “unknown” for the remainder of the analysis.

Assigning Animal Counts

Animal counts were estimated for each facility by dividing the mapped square footage of each barn by a square footage per animal. We obtained recommended square footage per animal from a literature review of standards, and they are listed below, along with their source.

Table 1. Square footage per animal type as derived from industry, academic or government guidelines

|

|

Square footage allotted to animal type

|

Source

|

|

Dairy

|

80 (based on 1100 - 1300 lb heifer)

|

Penn State Extension

|

|

Cattle

|

35 (average of access to yard and no access to yard)

|

Midwest Planning Service

|

|

Swine

|

7.4 (average of optimal economic and productivity)

|

National Pork Board

|

|

Poultry

|

.465 (layers)

|

United Egg Producers

|

Source: Penn State Extension, Midwest Planning Service, National Pork Board and United Egg Producers

Challenges With Poultry Animal Counts

Poultry production type (broilers, pullets, turkeys or egg layers) was unknown for each poultry facility Although square footage allotted per bird will vary based on production type, we applied guidelines on square footage for laying hens (67 square inches) to all poultry facilities. This choice was guided by data from the USDA 2012 Agricultural Census.

County-level inventory estimates for “pullets for laying flock replacement,” “broilers and other meat-type chickens,” “turkeys,” and “layers,” were added up for each county that touched the Maumee, then multiplied by the percentage of the county that lies within the watershed boundary.

Results showed that laying hens are the dominant poultry type (75 percent), followed by pullets (14 percent), turkeys (10 percent) and broilers (1 percent). Although the use of a single square footage per bird will introduce bias among the various poultry types, the inability to distinguish poultry type from aerial imagery required us to make certain assumptions. These biases include underestimating the number of laying hens, due to the 67 square inches per bird being applied to the building footprint and not accounting for modern high-rise laying houses, in which cage systems consist of enclosures arranged in rows and stacked in multiple tiers (USDA, Poultry Industry Manual).

As a result, the number of egg-laying hens in the Maumee basin and their phosphorus contribution may be seriously underestimated. Animal counts for other poultry types (pullets, broilers and turkeys) may be overestimated for barns housing these animals, as they are allocated more space per bird than the 67 square inches for layers used in this study.

Animal counts were estimated for each barn in the Maumee watershed. If a facility was permitted, animal counts from permit data were used rather than estimates using a square footage approach. This includes facilities in Indiana that could be matched to the township level permit data. Estimated animal counts in 2018 are listed in Table 2. Note that the 4,205,379-acre Maumee watershed lies primarily in Ohio (73 percent of land area), followed by Indiana (20 percent of land area) and Michigan (7 percent of land area).

Table 2. Estimated animal counts in the Maumee River Basin, as of 2018.

|

Estimated Animal Counts In the Maumee Basin (2018)

|

|

|

Indiana

|

Michigan

|

Ohio

|

Total

|

|

Dairy

|

12,949

|

15,494

|

69,834

|

98,277

|

|

Cattle

|

21,527

|

29,288

|

18,652

|

69,467

|

|

Swine

|

239,595

|

18,560

|

789,904

|

1,048,059

|

|

Poultry

|

4,610,857

|

285,076

|

14,323,216

|

19,219,149

|

|

Total

|

4,884,928

|

348,418

|

15,201,606

|

20,434,952

|

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management and Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality

Validation

Permitted data provided a means to validate the accuracy of the square footage methodology to assign animal counts. We compared animal counts listed for the 60 permitted facilities in Ohio to what the estimated count would be using a square footage approach. Results are displayed in Figure 1 below, with estimates above the permit count shown above the x-axis and estimates below the permit count shown below the x-axis.

This was performed for dairy, poultry and swine, as there was only one permitted beef cattle facility in the Ohio portion of the Maumee. For dairy and swine, there was an approximately equal amount of over- and under-estimation for each animal type. The average of all permitted swine facilities showed an overestimation of swine by 858 animals when using a square footage approach (standard deviation of 3,108). The average of all dairy facilities showed an underestimation of dairy by 92 cows (standard deviation of 680). However, poultry animal counts were underestimated in every case using the square footage approach (n = 7 permitted poultry facilities, 6 layer, 1 pullet). The average underestimation for layers was over 600,000 birds (standard deviation of > 1 million). Although this may indicate an underestimation of poultry basinwide, it also provides a level of conservatism for estimating overall poultry counts, which will include other poultry types besides layers.

Figure 1. Dairy, Poultry and Swine animal counts using Square Footage Methods Versus Permit Data

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture

Manure Production

The Midwest Planning Service (MWPS-18) “Manure Characteristics” was used to estimate manure production values (Table 3). We used information from permit data, supplemented by the USDA 2012 Ag Census, to inform the selection of a single daily production value (for manure, N and P205) for each animal type.

For beef cattle, daily production values were averaged among all animal sizes listed in Table 3. We were guided in this choice by an overall lack of information on cattle size for facilities in the Maumee, for which only three cattle permits were found. In addition, the Ag Census does not provide a means of determining the distribution of cattle size within a county.

For swine, we used permit data in Ohio to determine that growing pigs are the dominant animal type (> 90 percent of swine are greater than 55 pounds, n = 32 permits). Therefore, we chose to average production values for all sizes of swine listed (boars excluded) to represent an approximately 183 pound growing pig. Ohio permit data for dairy cattle showed that 99 percent of dairy animals (n = 17) are mature cows, which informed our decision to use manure and nutrient production values for a mature 1,400 pound dairy cow.

Manure production for laying hens was applied to all poultry rather than average values for layers and broilers, which was informed both by the dominance of laying hens in the USDA Ag Census (75 percent laying hens) and the overall underestimation of the number of chickens when compared to permit data. This resulted in a single value for manure, N and P2O5 production for each animal type in pounds per day (Table 4). P2O5 was multiplied by .44 to convert to elemental P in pounds per day (MWPS-18).

It is important to note that this number only reflects manure and nutrient production for each animal type and does not account for the addition of water for the purpose of washing or dilution. This can increase volumes of manure production by up to fourfold for liquid swine facilities (MWPS-18) but does not alter the phosphorus content of the manure. Long et al. also demonstrated that using as-excreted literature values may lead to over- or under-estimation of nutrient availability.

Table 3. MWPS Manure Production and Characteristics as produced, from MWPS-18.

|

|

Manure Production

|

|

Nutrient Content (lb/day)

|

|

|

Animal Type

|

Size, lb

|

lb/day

|

gal/day

|

N

|

P205

|

|

Dairy cattle

|

150

|

13

|

1.6

|

0.064

|

0.03

|

|

|

250

|

22

|

2.6

|

0.106

|

0.04

|

|

|

500

|

43

|

5.2

|

0.213

|

0.09

|

|

|

1000

|

86

|

10.4

|

0.425

|

0.17

|

|

|

1400

|

120

|

14.5

|

0.595

|

0.24

|

|

Beef cattle

|

500

|

30

|

3.6

|

0.17

|

0.13

|

|

|

750

|

45

|

5.3

|

0.26

|

0.19

|

|

|

1000

|

60

|

7.1

|

0.34

|

0.25

|

|

|

1250

|

75

|

8.9

|

0.43

|

0.31

|

|

Swine:

|

|

|

Nursery Pig

|

35

|

2.3

|

0.3

|

0.02

|

0.012

|

|

Growing Pig

|

65

|

4.2

|

0.5

|

0.03

|

0.022

|

|

Finishing Pig

|

150

|

9.8

|

1.2

|

0.07

|

0.05

|

|

|

200

|

13.1

|

1.6

|

0.09

|

0.067

|

|

Gestating Sow

|

275

|

9

|

1.1

|

0.07

|

0.05

|

|

Sow and Litter

|

375

|

22.5

|

2.7

|

0.1

|

0.055

|

|

Boar

|

350

|

11.5

|

1.4

|

0.09

|

0.064

|

|

Poultry:

|

|

|

Layers

|

4

|

0.21

|

0.026

|

0.0029

|

0.0025

|

|

Broilers

|

2

|

0.14

|

0.016

|

0.0017

|

0.0009

|

Source: Midwest Planning Service (MWPS-18)

Table 4. Manure and nutrient production per animal per day, adapted from MWPS-18.

|

|

Manure Production

|

Nutrient Content (lb/day)

|

|

Animal Type

|

lb/day

|

N

|

P205

|

P

|

|

Dairy

|

120

|

0.595

|

0.24

|

0.1056

|

|

Cattle

|

52.5

|

0.3

|

0.22

|

0.0968

|

|

Swine

|

10.15

|

0.0633

|

0.0426

|

0.0187

|

|

Poultry

|

0.21

|

0.0029

|

0.0025

|

0.0011

|

Source: EWG and ELPC via Midwest Planning Service

FINDINGS

Growth in Animal Feeding Operations

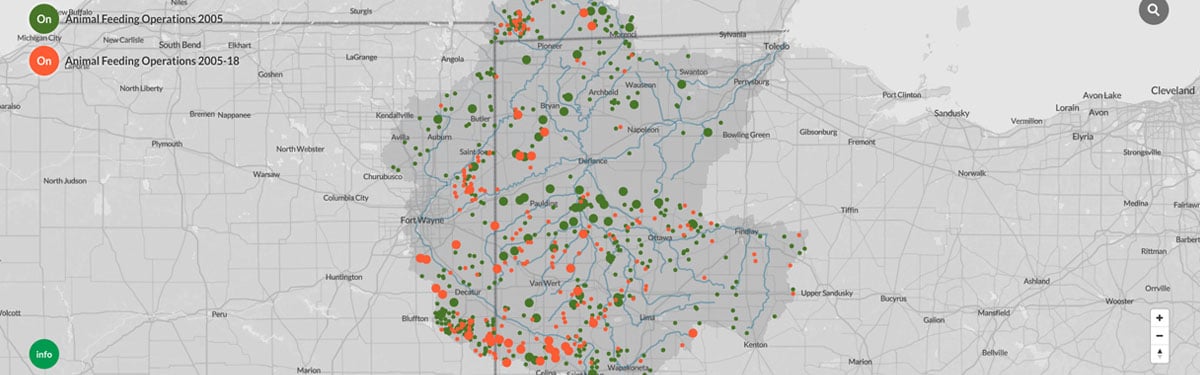

In 2005, we identified 545 animal feeding operations present in the Maumee River Basin. This included 178 swine, 153 cattle, 109 dairy and 105 poultry facilities. Between 2005 and 2018, 230 AFOs were constructed in the Maumee basin, equating to an average of 18 facilities added each year. The majority of growth was seen in poultry and swine, with 71 poultry facilities (31 percent of all new facilities) and 120 swine facilities (52 percent of all new facilities) constructed during this 13-year period.

By 2018, 775 AFOs were mapped in the Maumee Basin, which included 298 swine, 183 cattle, 118 dairy and 176 poultry facilities (Figures 2 and 3). Cattle and dairy production exhibited the slowest growth, with 30 cattle facilities and only nine dairy facilities added over the 13-year period.

Figure 2. Growth in AFO facilities in the Maumee River Basin by animal type (2005-2018).

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management and Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality

Figure 3. Animal facilities in the Maumee River Basin by state (2018).

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management and Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality

Expansion and Facility Characteristics

Of the 775 facilities present in 2018, 213 (27 percent) expanded since their first year of construction, during which either more buildings were added or existing buildings increased in size. To examine the change in facility characteristics over time, mean barn size and mean number of animals at each facility were compared for facilities built before and after 2005 (Table 5).

Both mean barn size and number of animals per facility decreased for cattle, whereas mean barn size and number of animals per facility increased for dairy, poultry and swine, in some cases substantially. For dairy, poultry and swine, mean barn size increased by 61 percent, 57 percent and 75 percent. Mean number of animals at each facility (which may include multiple barns) increased by 13 percent, 22 percent and 33 percent, respectively. These findings suggest that over time, AFO barns are getting larger and more animals are being housed at a single facility. This aligns with IJC 2017 results that show increased consolidation of animal facilities on the U.S. side of the Western Lake Erie Basin.

Table 5. Characteristics of facilities constructed before and after 2005.

|

|

Attribute

|

Pre-2005

|

Post 2005

|

|

Beef Cattle

|

Mean barn size (square footage)

|

5,740

|

4,171

|

|

Mean no. of animals at each facility (all barns)

|

389

|

330

|

|

Dairy Cattle

|

Mean barn size (square footage)

|

20,971

|

33,660

|

|

Mean no. of animals at each facility (all barns)

|

824

|

934

|

|

Poultry

|

Mean barn size (square footage)

|

14,141

|

22,268

|

|

Mean no. of animals at each facility (all barns)

|

79,259

|

97,017

|

|

Swine

|

Mean barn size (square footage)

|

11,140

|

19,495

|

|

Mean no. of animals at each facility (all barns)

|

3,115

|

4,154

|

Source: EWG and ELPC and Environmental Law Policy Center

Trends in Manure and Nutrient Production

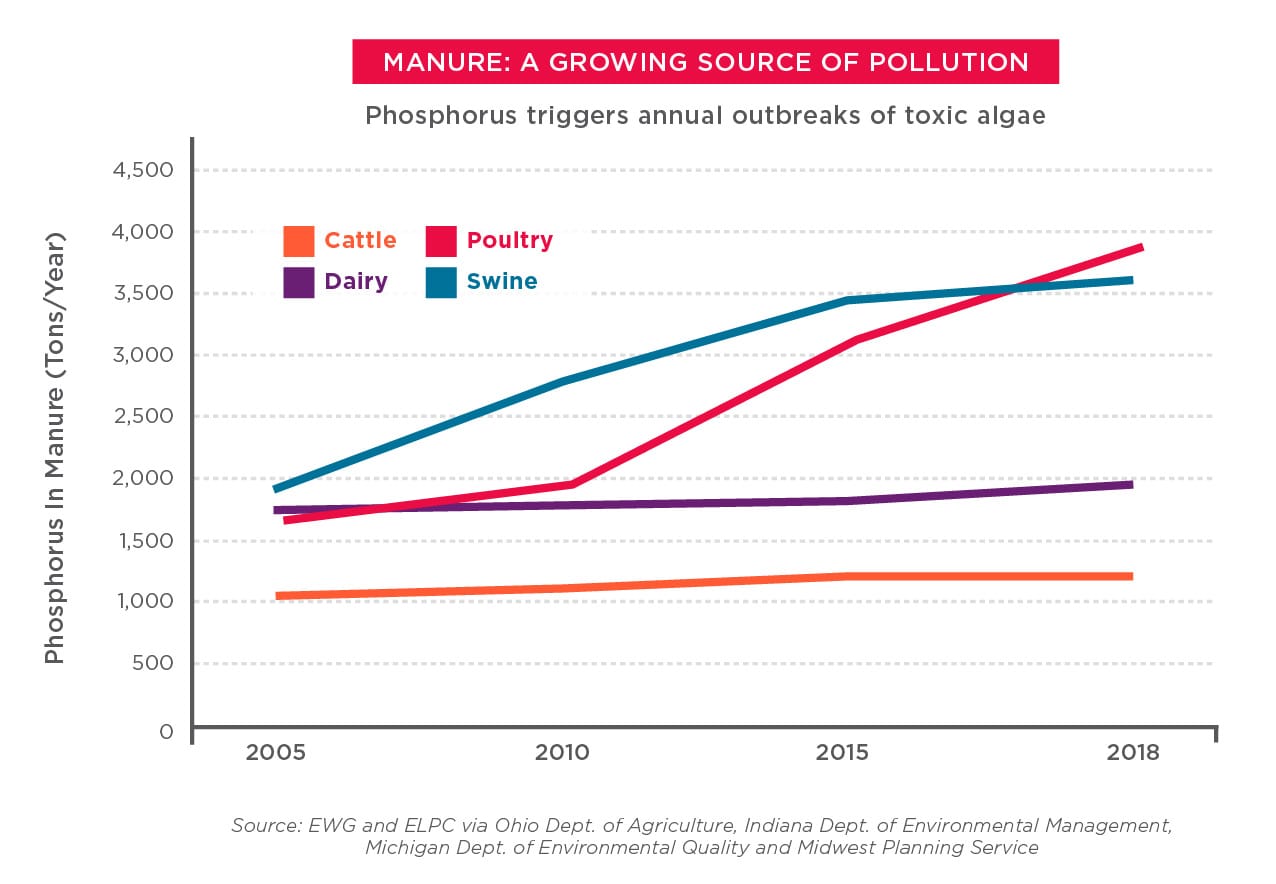

The amount of manure produced in the Maumee River basin has increased concurrently with the growth of new facilities (Figure 4). Dairy is consistently the largest producer of manure, followed by swine, cattle and poultry. Recent growth in poultry facilities has caused manure from chickens to now equal that of beef cattle in the Maumee basin.

As poultry manure contains more phosphorous than other animal manures, chickens now rival and even exceed swine in phosphorus production in the Maumee basin (Figure 5). Based on numbers from the MWPS-18, poultry manure from egg-laying hens is estimated to have two to three times the amount of phosphorus per pound of manure than beef cattle or hogs, and nearly six times the amount of phosphorus than dairy cattle.

Manure production in the Maumee has increased by 43 percent over the period of study, from 3.9 million tons per year in 2005 to 5.5 million tons per year in 2018. Phosphorus production has increased 67 percent, from 6,348 tons per year in 2005 to 10,610 tons per year in 2018 (Table 6).

Figure 4. Manure Production in the Maumee River Basin, 2005-2018.

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management, Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality and Midwest Planning Service

Figure 5. Phosphorus Production in the Maumee River Basin, 2005-2018.

Source: EWG vand ELPC ia Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management, Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality and Midwest Planning Service

Table 6. Manure and Phosphorus Production in the Maumee River Basin by Animal Type, 2005-2018.

|

Animal Type

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2018

|

|

Manure Production (tons/year)

|

|

Cattle

|

570,813

|

599,815

|

665,581

|

665,581

|

|

Dairy

|

1,960,225

|

2,021,480

|

2,069,243

|

2,178,349

|

|

Poultry

|

318,949

|

373,174

|

593,234

|

736,574

|

|

Swine

|

1,027,116

|

1,507,520

|

1,860,483

|

1,950,584

|

|

Total

|

3,877,103

|

4,501,989

|

5,188,541

|

5,531,088

|

|

Phosphorus Production (tons/year)

|

|

Cattle

|

1,052

|

1,106

|

1,227

|

1,227

|

|

Dairy

|

1,725

|

1,779

|

1,821

|

1,917

|

|

Poultry

|

1,671

|

1,955

|

3,107

|

3,858

|

|

Swine

|

1,900

|

2,788

|

3,441

|

3,608

|

|

Total

|

6,348

|

7,628

|

9,597

|

10,610

|

Source: EWG and ELPC via Midwest Planning Service

Permitted Facilities

Each of the three states in the Maumee River basin (Indiana, Ohio and Michigan) has its own regulations about whether an AFO requires a permit. This depends largely on the number of animals housed at each facility. We examined permitted facilities by state to determine the number and type of operations permitted in the Maumee basin as of 2018. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the percentage of facilities permitted by state and animal type.

Overall, 155 of the 775 AFOs, or 20 percent, were permitted. The highest percentage of facilities permitted was in Indiana (36 percent), which has the most stringent permitting regulations of the three states. In Ohio, 14 percent of facilities were permitted; in Michigan, only 7 percent. Swine and dairy were the most commonly permitted, with 32 percent and 31 percent of facilities permitted, respectively. Only 12 percent of poultry and 2 percent of cattle facilities had permits.

Figure 6. Percentage of Animal Feeding Operations in the Maumee Permitted by State

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management and Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality

Figure 7. Percentage of Animal Feeding Operations in the Maumee Permitted by Animal Type

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management and Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality

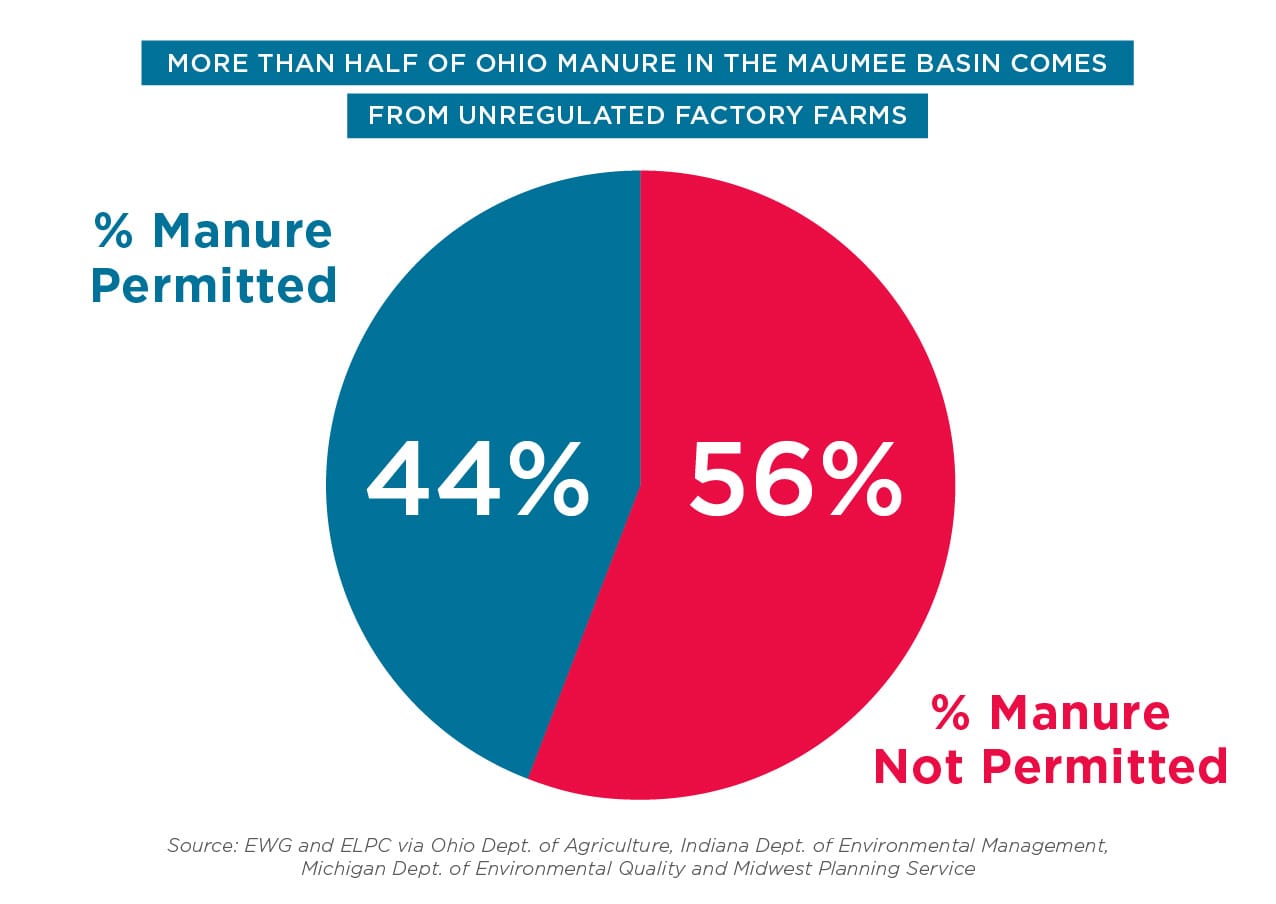

Permitted Manure in Ohio

Ohio accounts for 74 percent of animals and 68 percent of manure production in the Maumee Basin. To estimate the percentage of manure captured through permitted data in Ohio, manure production from permitted facilities was compared to manure production from all facilities. Results are shown in Table 7.

More than half (56 percent) of the total estimated manure production is not captured by permitted facilities in the Ohio portion of the Maumee. An estimated 79 percent of hog manure, 51 percent of chicken manure, 34 percent of dairy manure and 84 percent of cattle manure is unaccounted for. With only 9 percent of poultry facilities permitted in Ohio but nearly half of the poultry manure accounted for, this would suggest that the few permitted poultry facilities account for the majority of the manure produced.

We also saw this with dairy facilities, in which 66 percent of manure is captured by the 27 percent of facilities permitted. In contrast, permitted facilities for swine and beef cattle make up a much smaller proportion of the manure produced by these animals in the Ohio portion of the Maumee.

Table 7. Permitted Manure in Ohio (2015)

|

|

Number of

facilities permitted

|

Number of

facilities mapped

|

Manure production

from all facilities

(tons/year)

|

Manure production

from all facilities

(tons/year)

|

% Manure

Unpermitted

|

|

Cattle

|

1

|

36

|

28,935

|

178,709

|

84

|

|

Dairy

|

20

|

74

|

1,034,249

|

1,555,448

|

34

|

|

Poultry

|

8

|

91

|

268,915

|

548,937

|

51

|

|

Swine

|

31

|

221

|

302,765

|

1,472,384

|

79

|

|

TOTAL

|

60

|

422

|

1,634,865

|

3,755,479

|

56

|

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture

Watershed Analysis

Phosphorus production from animal manure in the Maumee was summed within each HUC12 watershed (Figure 8). There are 252 watersheds in the Maumee Basin, 70 of which do not contain any AFOs. Half of the total phosphorus production from animal operations in the Maumee can be accounted for in just 30 HUC12 watersheds.

Platter Creek produces the most phosphorus of any HUC12 in the Maumee. It contains just four AFOs but accounts for 9 percent of total P production from animal manure in the Maumee. Platter Creek is home to both the largest poultry and largest beef cattle operation in the Maumee. The poultry operation houses more than four million egg-laying hens (more than three times the number of the next largest facility), and the cattle operation houses more than 3000 cattle. Both operations have permits.

Figure 8. Phosphorus Production from Animal Manure by HUC12 Watershed in the Maumee Basin.

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture, Indiana Dept. of Environmental Management, Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality and Midwest Planning Service

Distressed Watersheds

Eight watersheds in Ohio were proposed to receive a distressed designation in 2018 by former Gov. John Kasich (Figure 9).

Of the HUC12 watersheds estimated to produce between 75 and 150 tons of phosphorus per year, 24 of the 33 (73 percent) fall within a proposed distressed watershed. Of the HUC12 watersheds estimated to produce more than 150 tons of phosphorus per year, five of the 14 (36 percent) are located within a distressed watershed. More than half (56 percent) of the total phosphorus from animal manure in the Maumee is produced from the 345 animal operations in the eight distressed watersheds. We estimate that Platter Creek generates the most phosphorus from animal manure of any HUC12 watershed in the Maumee Basin. It is also the only stand-alone distressed watershed proposed in 2018.

Figure 9. Ohio Proposed Distressed Watersheds

Source: EWG and ELPC via Ohio Dept. of Agriculture

Source of Phosphorus

Data on commercial fertilizer in the Maumee basin was obtained from the Nutrient Use Geographic Information System, or NUGIS, of the International Plant Nutrition Institute, or IPNI. IPNI has compiled a nationwide database of county-level fertilizer sales provided by the Association of American Plant Food Control Officials, or AAPFCO. These data are separated into farm and non-farm uses, and additional quality control steps are taken by IPNI to account for errors and reduce spatial bias.

Nutrient data is then aggregated from the county to the watershed scale. Yearly watershed level data on tons of P205 excreted from livestock manure were pulled directly from the IPNI database for the Maumee River Basin to estimate trends in commercial fertilizer input over time. Farm fertilizer P205 was multiplied by .44 to convert to elemental P.

IPNI data were provided at five-year intervals corresponding to the USDA Agricultural Census between 1987 and 2007 (1987, 1992, 1997, 2002 and 2007) and yearly between 2008 to 2014. To compare phosphorus production from commercial fertilizer to animal manure estimates from this study, IPNI data were pulled for the years 2007 through 2014. Results suggest that commercial fertilizer rates are gradually declining, which has been documented by numerous other studies (Figure 10; IJC, 2018; Kast, 2018).

Once they are published, it will be valuable to examine more recent IPNI data to estimate the rate of this downward trend in commercial fertilizer use. Over the same time period, phosphorus production rates from animal manure in the Maumee increased by 67 percent. When summing the two nutrient sources, we do not see an overall increase in phosphorus production in the Maumee but rather a shift in the relative contribution of the major agricultural sources.

Figure 10. Phosphorus Production by Agricultural Source in the Maumee Basin.

Source: EWG and ELPC via International Plant Nutrition Institute

REFERENCES

D’Anglada, L., Gould, C., Thur, S., Lape, J., Backer, L., Bricker, S., Clyde, T., Davis, T., Dortch, Q., Duriancik, L., Emery, E., Evans, M.A., Fogarty, L., Friona, T., Garrison, D., Graham, J., Handy, S., Johnson, M.-V., Lee, D., Lewitus, A., Litaker, W., Loeffler, C., Lorenzoni, L., Malloy, E.H., Makuch, J., Martinez, E., Meckley, T., Melnick, R., Myers, D., Ramsdell, J., Rohring, E., Rothlisberger, J., Ruberg, S., Ziegler, T. (2018). “Harmful Algal Blooms and Hypoxia in the United States: A Report on Interagency Progress and Implementation.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Environmental Protection Agency, 2010. Ohio Lake Erie Phosphorus Task Force Final Report. Available at: https://epa.ohio.gov/portals/35/lakeerie/ptaskforce/Task_Force_Final_Report_April_2010.pdf

Goolsby, D.A., Battaglin, W.A., Lawrence, G.B., Artz R.S., Aulenbach B.T., Hooper R.P., Keeney D.R. and Stensland G.J. 1999. Flux and sources of nutrients in the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin; Topic 3. Report for the Integrated Assessment on Hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Coastal Ocean Program Decision Analysis Series No. 17. NOAA, Silver Spring, MD

International Joint Commission. Fertilizer Application Patterns and Trends and Their Implications for Water Quality in the Western Lake Erie Basin, 2018.

Kast, J. Manure Management in the Maumee River Watershed and Watershed Modeling to Assess Impacts on Lake Erie’s Water Quality. Ohio State University, 2018.

Long, C.M., Muenich, R.L., Kalcic, M.M., and Scavia, D. 2017. Impacts of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and manure on nutrient inputs in a watershed. IAGLR 2017 Annual Meeting, Detroit, Michigan, Abstracts, p. 244.

Maccoux MJ, Dove A, Backus SM, and Dolan DM. 2016. Total and soluble reactive phosphorus loadings to Lake Erie: a detailed accounting by year, basin, country, and tributary. J Great Lakes Res 42: 1151–65.

MWPS-11, Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook. Amend. IA-3, July 2013. MidWest Plan Service (MWPS): Ames, Iowa.

MWPS-18, Livestock Waste Facilities Handbook, 1993. MidWest Plan Service (MWPS): Ames, Iowa.

National Pork Board, Pig Space: Finding the Right Fit. Farm Journal’s Pork, January 18, 2011.

Penn State Extension. Recommendations for Calf and Heifer Housing Dimensions for Holsteins. May 2016.

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com.

Poultry Industry Manual, FAD Prep Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness & Response Plan. March 2013. United States Department of Agriculture, National Animal Health Emergency Management System.

Scavia, D.; Kalcic, M.; Muenich, R.L.; Aloysius, N.; Boles, C.; Confessor, R.; DePinto, J.; Gildow, M.; Martin, J.; Read, J. Informing Lake Erie Agriculture Nutrient Management via Scenario Evaluation; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016.

United Egg Producers, Compete Guidelines for Cage and Cage-Free Housing. Animal Husbandry Guidelines for U.S. Egg-Laying Flocks, 2017.

USDA NASS, 2012 Census of Agriculture, Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2012/