Contamination of Iowa’s Private Wells: Methods and Detailed Results

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 24, 2019

By Anne Schechinger, Senior Analyst of Economics

Des Moines Water Works has struggled for years to provide safe drinking water to its customers, battling nitrate contamination from upstream farms. But contamination from agricultural practices may be even worse for the estimated 230,000 to 290,000 Iowans1 whose drinking water comes from private wells, an investigation by Environmental Working Group and Iowa Environmental Council finds.

In these private wells, nitrate is not the only problem. Unsafe levels of nitrate, coliform bacteria and fecal coliform bacteria were found in thousands of wells across Iowa between 2002 and 2017.

Both contaminants have serious impacts on public health. For public water systems, the legal limit of nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams per liter, or mg/L, because a potentially fatal condition for infants, called blue baby syndrome, can occur at levels at or above that limit. But numerous studies have found increased rates of colon,2 rectal,3 bladder4 and ovarian5 cancers, as well as birth defects,6 at nitrate concentrations of just 5 mg/L or above.

Most coliforms and fecal coliforms in drinking water are not harmful in themselves.7 The Environmental Protection Agency requires public water systems to test for these bacteria to evaluate if other dangerous pathogens, such as typhoid, are present. However, some strains of E. coli are harmful themselves, causing diarrhea, vomiting and even death.

According to the EPA, there is no safe level of coliforms or fecal coliforms in drinking water, since their presence indicates the presence of other potentially harmful pathogens. A public water system violates the EPA’s regulations if more than 5 percent of its tests in a month are positive for total coliforms, or if a system tests positive for coliforms once and then the follow-up test done within 24 hours is positive for fecal coliforms.8 The actual number of bacteria in each test doesn’t matter, what matters is only whether the test is positive or negative.

Even though these contaminants can affect public health, no federal or state department requires all private wells to be tested or regulated. The only private well testing regulation that exists in Iowa is that wells must be tested once, when they are newly constructed or repaired.9 Well owners are left on their own to make sure their drinking water is safe.

Agriculture is a leading cause of nitrate and bacteria contamination of private wells.10 Both fertilizer and animal manure contain nitrate, and manure contains bacteria. When farmers apply fertilizer and manure to farm fields, these contaminants can penetrate the soil and pollute groundwater.11 They can also run off fields and seep directly into wells or surface water sources and pollute wells whose groundwater is affected by surface water.

How We Did the Study

The well data analyzed by EWG came from the Private Well Tracking System organized by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, or DNR.12 Through public records requests, we received the results of nitrate, coliform and fecal coliform bacteria tests conducted at each private well in Iowa between 2002 and 2017. Most of the wells were “household” wells and thus used in homes instead of for irrigation or other uses, and most were active at the time of the tests.13

It’s important to note that the database does not include every private well in Iowa. There is no record of all the private wells in the state, since many were built before the state required tests to be performed during construction. Additionally, for all wells that are recorded in state databases, not every one has been tested for these contaminants.

For the nitrate tests, we received the actual nitrate concentrations found during each well test. Unknown nitrate concentrations were converted into 0 mg/L values in the nitrate data. For the bacteria tests, we received data that showed whether the test was positive for coliforms, fecal coliforms or neither bacteria.

The analysis began in 2002, one of the first regular test years.14 All nitrate tests between December 12, 2013, and February 4, 2015, were removed from the analysis due to inaccuracy. When some of the records from that period were added to the DNR’s database, the numbers were accidentally increased. DNR sent what it termed corrected data, but the new data were not in line with previous and later years. This led us to believe that those were not accurate, either.15

For the analysis, nitrate concentrations and bacteria presence in each test were analyzed on an individual well basis, as well as aggregated to a county level for summary statistics.

Most of the well tests in the Private Well Tracking System come from Iowa’s Grants to Counties Program. The database also contains well tests performed during well constructions, renovations and pluggings.16

The Grants to Counties Program is Iowa’s largest well testing program. The state provides around $30,000 to each county every year, and that money goes toward testing private wells for nitrate, coliforms and fecal coliforms.17 Well owners do not pay for well tests through this program. Marshall County is the only county that does not participate in the program.

Participation in the Grants to Counties Program is voluntary and usually initiated by the well owner.18 This is a deterrent to testing , because in most counties, well owners who want to get tested must know about the program and whom to ask for the test. Better marketing and public education could result in many more wells getting tested.

If you are an Iowa resident who uses a private well and want to find out whether your drinking water contains nitrate or bacteria, consult this list to find your county sanitarian and ask for a free well test through the Grants to Counties Program.

Detailed Results

Bacteria Analysis

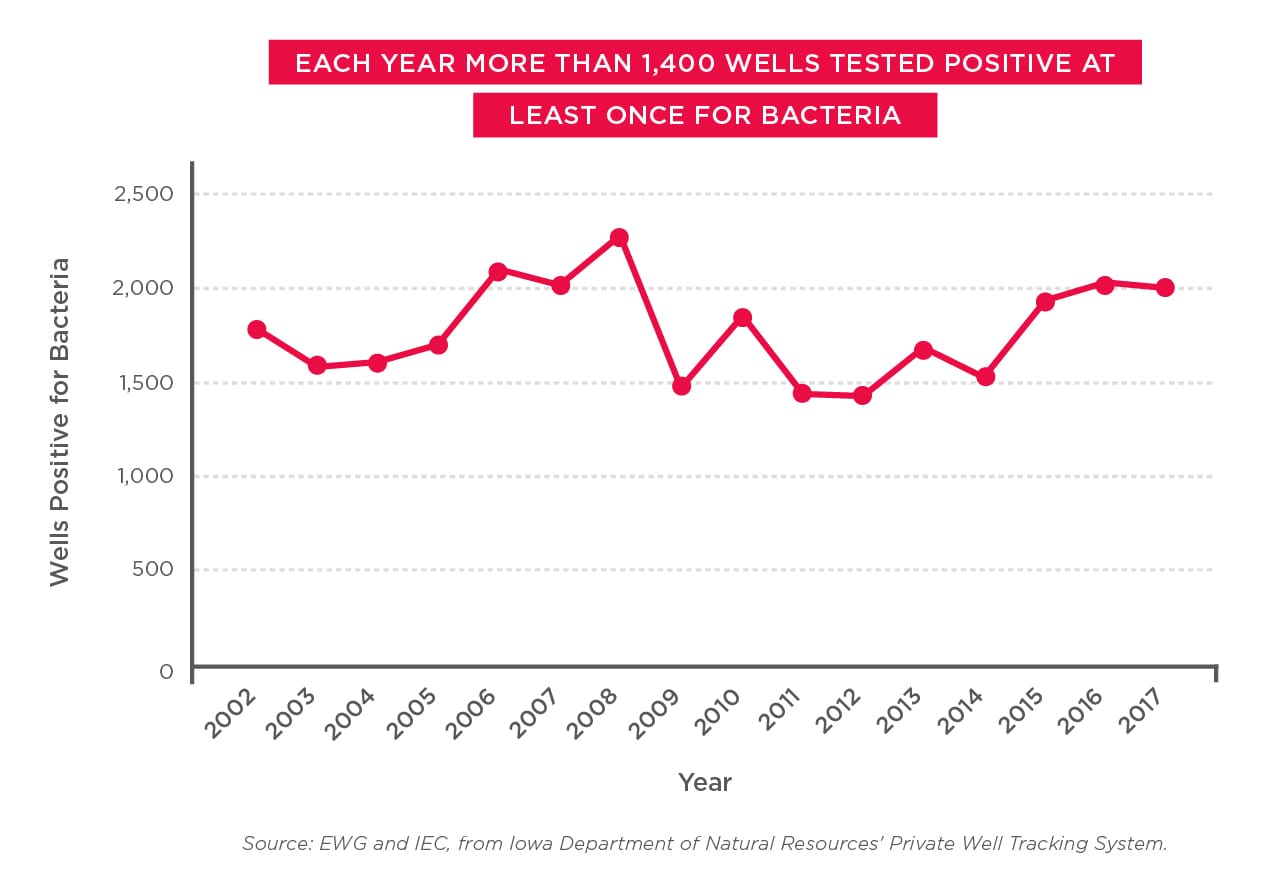

Any presence of coliform or fecal coliform bacteria in drinking water is potentially unsafe, according to the EPA.19 Between 2002 and 2017, 54,841 private wells in Iowa were tested for coliforms or fecal coliforms. At least one test was positive for bacteria in 41 percent of the wells, or 22,228, wells. And 7.9 percent, or 4,318 wells, tested positive for bacteria every time they were tested.

Of all the bacteria tests, 22 percent were positive for either coliforms or fecal coliforms. Coliforms were present more often than fecal coliforms (Figure 1). 34 percent were positive for coliforms and 6 percent for fecal coliforms.

Figure 1. More tests were positive for coliforms than fecal coliforms

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

The presence of bacteria depends on well depth. Wells less than 50 feet deep, which are vulnerable to contamination, had bacteria more often. 34 percent of wells less than 50 feet deep tested positive for bacteria. For wells between 50 and 150 feet deep, only 22 percent of tests had bacteria, and for wells greater than 150 feet deep, 18 percent of tests were positive for bacteria (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Deeper wells were less likely to have bacteria

|

Well Vulnerability (depth)

|

All tests

|

Tests positive for bacteria

|

Percent of tests positive for bacteria

|

|

High Vulnerability (<50 ft)

|

21,506

|

7,362

|

34%

|

|

Intermediate Vulnerability (50–150 ft)

|

88,382

|

19,670

|

22%

|

|

Low Vulnerability (>150 ft)

|

72,902

|

12,758

|

18%

|

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

Seasons seem to play a part in bacteria presence in wells. More tests were positive for bacteria during summer than during any other season, with the largest percentages of positive tests for coliforms during July, August and September. The highest percentages of positive tests for fecal coliforms were in June, July and August.

Nitrate Analysis

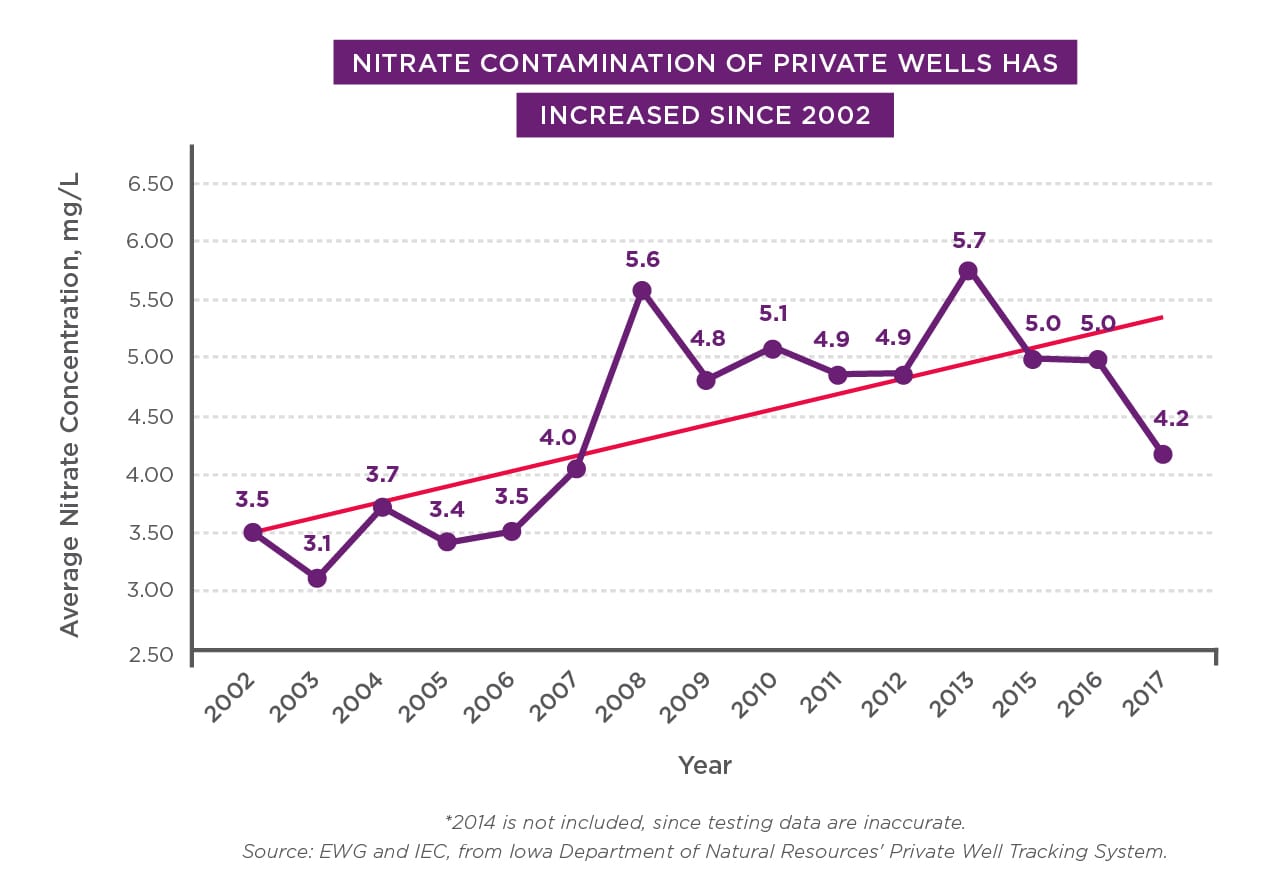

Excluding 2014 because of inaccurate data, 54,994 wells were tested for nitrate between 2002 and 2017. Across all wells, the average nitrate concentration was 4.4 mg/L, which is very close to the 5 mg/L concentration associated with increased rates of birth defects and cancer. Average nitrate levels showed a statistically significant upward trend over time (Figure 3). Annual nitrate averages were all below 4 mg/L between 2002-2006, and they have all been above 4 mg/L in the more recent years of 2007-2017.

Figure 3. Average nitrate concentrations have gone up over time

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

More than 22 percent, or 12,316, wells, had overall nitrate averages at or above the potentially dangerous 5 mg/L level. And 12 percent, or 6,637, wells had averages at or above the legal limit of 10 mg/L (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percent of wells with nitrate averages at or above 5 or 10 mg/L varied over time

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

Many wells had very high nitrate averages, far above 10 mg/L. More than 1,000 wells had average nitrate concentrations at or above 30 mg/L, and 499 wells had average nitrate at or above 50 mg/L. A total of 237 tests conducted on 187 wells each had nitrate concentrations at or above 100 mg/L. These higher-concentration tests occurred more often in recent years. Almost 75 percent of these tests happened between 2010 and 2017.

Well depth also affected the wells’ average nitrate concentrations. High vulnerability wells less than 50 feet deep had the highest nitrate average, 8.8 mg/L. Intermediate vulnerability wells had a lower average, 4.4 mg/L, and low vulnerability wells had the lowest nitrate average of 2.9 mg/L (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Deeper wells had lower average nitrate concentrations

|

Well Vulnerability (depth)

|

Average nitrate concentration, mg/L

|

|

High Vulnerability (<50 ft)

|

8.79

|

|

Intermediate Vulnerability (50–150 ft)

|

4.35

|

|

Low Vulnerability (>150 ft)

|

2.90

|

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

Testing Frequency Analysis

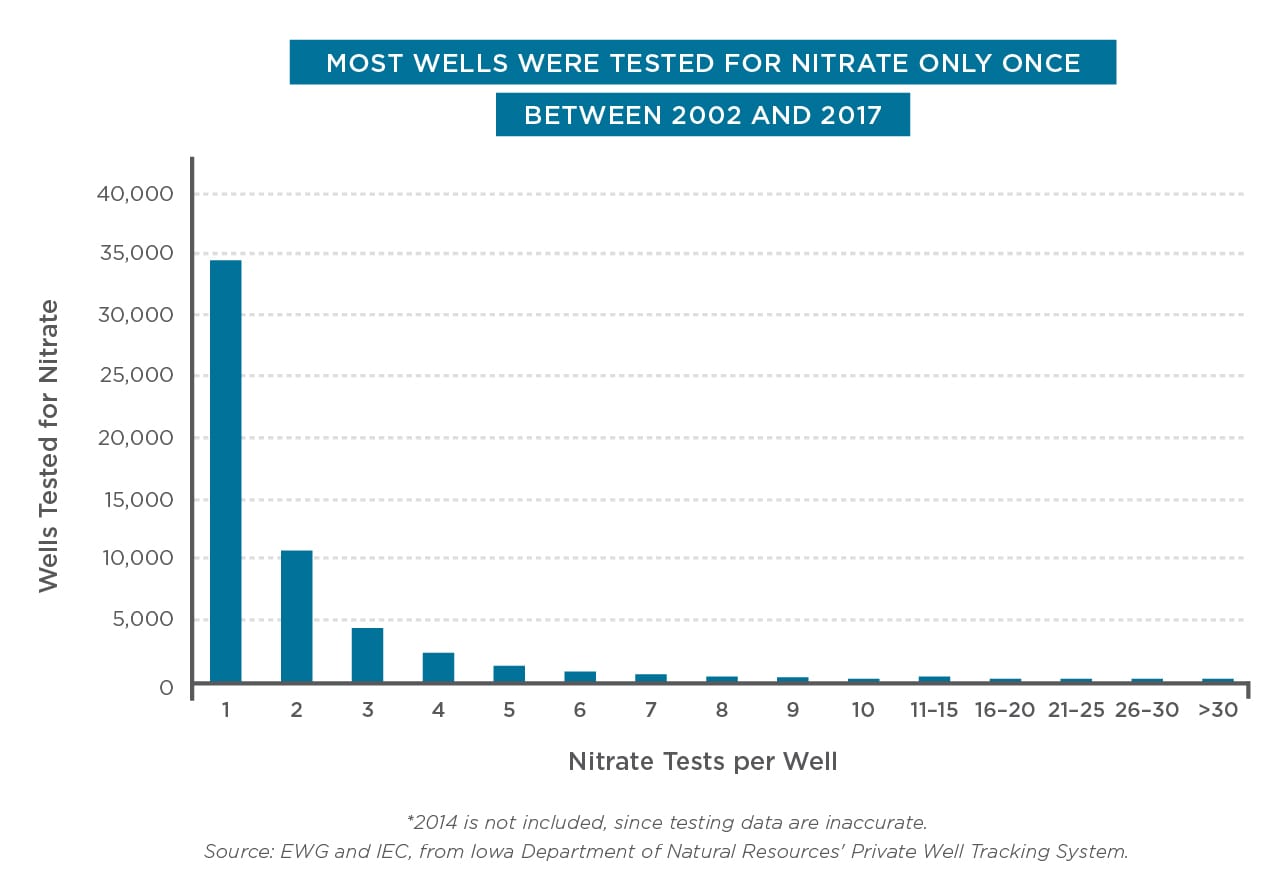

Wells are tested so infrequently that the true scope of the contamination problem is likely not fully understood. Although the numbers of bacteria tests have increased since 2002, annual nitrate tests have mostly stayed the same. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources recommends, but does not require, that owners test wells for nitrate and bacteria at least once every year.20 But almost 63 percent of wells were only tested for nitrate once between 2002 and 2017, excluding 2014 (Figure 6). Only 10 wells were tested for nitrate every year.

Figure 6. Almost two-thirds of wells were only tested once for nitrate

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

61 percent of wells tested for coliforms and 62 percent tested for fecal coliforms were only tested once in 16 years. Only 12 wells were tested every year for coliforms, and there was only one well that was tested every year for fecal coliforms.

Wells tested more frequently show higher levels of contamination. More than 3,000 wells were tested more than five times for nitrate between 2002 and 2017, and they showed a nitrate average of 4.83 mg/L, which was higher than the average for all wells. For wells tested for bacteria five or more times, 24 percent were positive for bacteria, compared to 22 percent for all tests.

Many of the counties with the highest nitrate averages and the largest percentages of positive bacteria tests test infrequently. More testing is needed in these counties. Seven of the 10 counties with the highest nitrate averages conducted 100 tests or less between 2002 and 2017, excluding 2014 (Figure 7). Shelby, Taylor and Fremont counties had the highest nitrate averages among the top 10 counties that tested more than 100 times.

Figure 7. Seven of 10 counties with the highest nitrate averages had less than 100 tests

|

County

|

Average nitrate concentration

|

Total number of tests

|

|

Wayne

|

59.00

|

2

|

|

Lyon

|

46.82

|

31

|

|

Shelby

|

41.46

|

696

|

|

Taylor

|

30.22

|

151

|

|

Poweshiek

|

29.77

|

55

|

|

Decatur

|

24.14

|

14

|

|

Fremont

|

20.23

|

571

|

|

Clarke

|

16.62

|

92

|

|

Appanoose

|

16.13

|

14

|

|

Union

|

15.92

|

69

|

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

For the counties with the top 10 highest percentages of positive bacteria tests, six out of 10 had 31 tests or fewer (Figure 8). Cherokee County conducted the most tests in the top 10, with 416 tests, but had the 10th highest percent of positive bacteria tests.

Figure 8. Six out of 10 counties with the highest percentages of positive bacteria tests had 31 tests or less

|

County

|

Positive bacteria tests

|

Total number of tests

|

Percent of positive bacteria tests

|

|

Adams

|

23

|

30

|

77%

|

|

Wayne

|

3

|

4

|

75%

|

|

Union

|

69

|

97

|

71%

|

|

Appanoose

|

22

|

31

|

71%

|

|

Obrien

|

83

|

123

|

67%

|

|

Sioux

|

6

|

9

|

67%

|

|

Taylor

|

167

|

251

|

67%

|

|

Lucas

|

8

|

13

|

62%

|

|

Davis

|

6

|

10

|

60%

|

|

Cherokee

|

236

|

416

|

57%

|

Source: EWG, from Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Private Well Tracking System

Lower-income counties did not do much testing, either. Decatur, Wayne, Appanoose, Wapello and Van Buren counties in southern Iowa had the lowest 2016 median household incomes – all were at or below $45,000 a year.21 This is much smaller than the $56,354 that was the 2016 median income for the state. Wapello County conducted 41 nitrate tests, but the other 4 counties only conducted 15 nitrate tests or less. For bacteria, Wapello County performed 70 tests, but the other four counties only conducted 31 tests or fewer.

Decatur, Wayne and Appanoose counties were among the top 10 counties with the highest nitrate averages, whereas Wayne and Appanoose were in the top 10 counties with the highest percentages of positive bacteria tests. These lower-income counties did not test often, and when they did, they found high levels of nitrate and more frequent bacteria presence.

Discussion

Nitrate and bacteria contamination of private wells is a difficult and expensive problem. Pollution can occur because the well is broken or structurally unsound, so the state Hygienic Laboratory at the University of Iowa recommends that well owners first check for damage if they find bacteria.22 If there is damage, well owners should get the well repaired. But if nothing is wrong, owners of contaminated wells have two options: mitigation or water treatment.

For mitigation, well owners can dig their current well deeper in hopes of hitting cleaner water, or they can dig an entirely new well. But neither option guarantees cleaner water, especially in the long term, if the contamination problem persists in the groundwater source. Some well owners can also plug their well and buy water from a rural water system, but that option is not always available. And all these options are potentially very expensive.

Distillation, reverse osmosis and ion exchange are the main options for treating well water contaminated with nitrate.23 Distillation systems heat well water to form steam, and the steam does not contain nitrate. The steam is then cooled to form clean water. Reverse osmosis systems push pressurized water through a membrane that filters out nitrate and other contaminants. Ion exchange treatment systems contain a resin that removes nitrate as water passes through it.

These treatment systems can also be expensive. Costs depend on the amount of water treated each day, as well as the electricity consumed by the treatment systems. These systems can cost more than a thousand dollars initially, and hundreds of dollars a year to operate and maintain (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Treating well water to remove nitrate, or digging a new well, is expensive

|

Method

|

Initial Costs

|

Annual Costs

|

|

Distillation (4–10 gal/day)

|

$304-$1,827

|

$487-$609 + electricity

|

|

Reverse Osmosis (2–10 gal/day)

|

$365-$1,583

|

$122-$365 + electricity

|

|

Ion Exchange (based on tank size)

|

$731-$2,679

|

$3.65-$4.87 per bag of salt

|

|

New Well

|

$3,504-$17,519

|

$0

|

Source: EWG, from Robert Mahler et al., Quality Water for Idaho, Nitrate and Groundwater. University of Idaho Extension, July 2007. Available at cals.uidaho.edu/edcomm/pdf/CIS/CIS0872.pdf, and A.M. Lewandowski et al., Groundwater Nitrate Contamination Costs: A Survey of Private Well Owners. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, May/June 2008. Available at www.house.leg.state.mn.us/comm/docs/JSWC2008CostofNitrateContamination.pdf

If bacteria contamination of a private well is a one-time occurrence, perhaps because of a flood, well owners can disinfect with shock chlorination, adding chlorine to the well to kill all the bacteria.24 But disinfection through chlorination and ultraviolet light treatment systems are the options for longer-term coliform and fecal coliform bacteria contamination.25

Chlorination systems provide chlorine to well water to kill the bacteria, and many of these systems also have carbon filters to remove the chlorine taste and potential disinfection byproducts. Ultraviolet systems shine ultraviolet light on well water to kill bacteria.

The cost of these systems varies based on the amount of water treated each day, and whether homeowners want to install them themselves or have them professionally installed. Professionally installed chlorination systems can cost more than $3,000 for high-capacity systems,26 and UV systems can cost between $1,500 and $1,600.27 And that does not even include annual operating and maintenance costs.

Solutions

Since mitigation or treatment to fix nitrate and bacteria contamination can be such an expensive problem, preventing these contaminants from getting into private well water in the first place would be a better solution. See our recommendations on how to fix this contamination issue here.

4 RR Jones et al., Nitrate from Drinking Water and Diet and Bladder Cancer Among Postmenopausal Women in Iowa. Environmental Health Perspectives, November 2016. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27258851

5 M Inoue-Choi et al., Nitrate and Nitrite Ingestion and Risk of Ovarian Cancer Among Postmenopausal Women in Iowa. International Journal of Cancer, July 2015. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25430487

6 JD Brender et al., The National Birth Defects Prevention Study, Prenatal Nitrate Intake from Drinking Water and Selected Birth Defects in Offspring of Participants in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, September 2013. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23771435

15 Private Correspondence with Russell Tell, Senior Environmental Specialist. Iowa Department of Natural Resources, October 2018.