Methodology and Detailed Results: In Farm Country, Nitrate Pollution of Drinking Water Is Getting Worse

By Anne Schechinger, Senior Analyst, Economics

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24, 2020

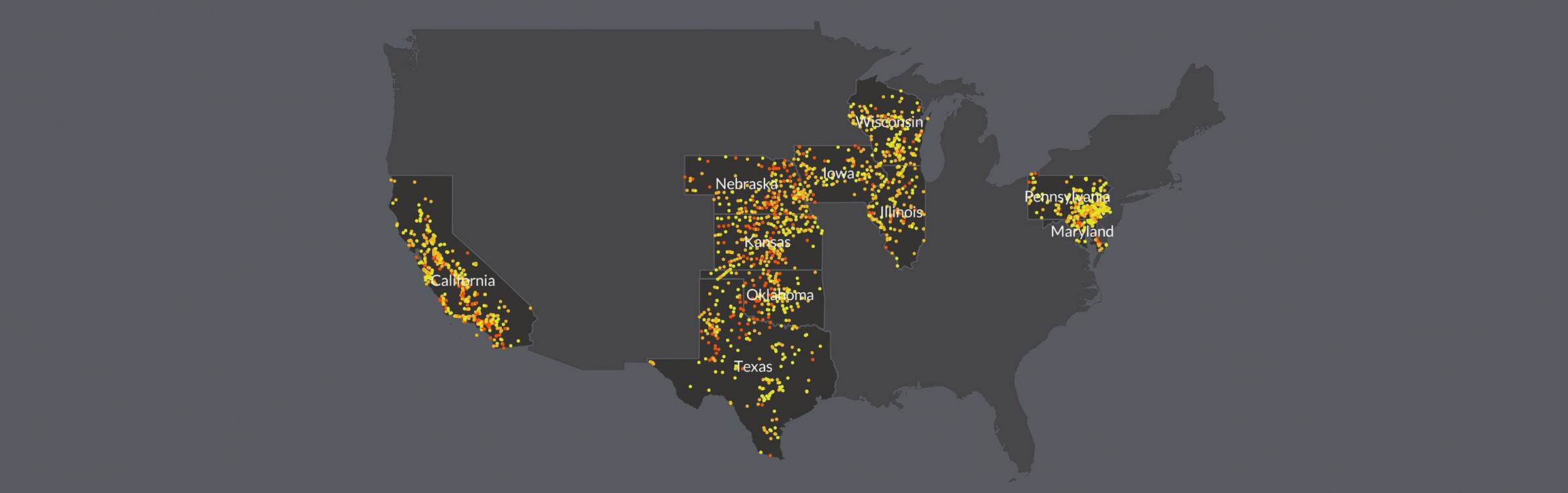

In 2019’s Trouble in Farm Country Revisited[1] report, the Environmental Working Group reported that nitrate contamination of drinking water was rampant in 11 states – California, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin. In March 2020, we found that more than 200,000 people in Minnesota were drinking water with nitrate contamination that got worse between 1995 and 2018.[2] Now new research from EWG shows that nitrate levels in community drinking water have also been increasing in the other 10 states over the past 15 years.

Between 2003 and 2017, tests detected elevated levels of the chemical in the tap water supplies of 4,037 community water systems serving almost 45.5 million residents in California, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin. Contamination is getting worse in 52 percent, or 2,111, of these communities.

This increasing contamination does not just affect groundwater systems. Contamination in both groundwater and surface water systems is getting worse. And although there are not enough data to evaluate whether nitrate levels are getting worse in private wells over time, it is likely that nitrate levels are increasing in wells that households use for drinking, because they often draw water from the same sources as groundwater community water systems.

Nitrate is a chemical component of fertilizer and manure. It gets into groundwater and surface water sources of drinking water by running off farm fields and seeping into groundwater.

Drinking water with nitrate can have serious health consequences. Under the federal Clean Water Act, the legal limit for nitrate (measured as nitrogen) in drinking water is 10 milligrams per liter, or mg/L. This limit was set in 1962 to guard against so-called blue baby syndrome, a potentially fatal condition that starves infants of oxygen if they ingest too much nitrate.[3] But newer research indicates that drinking water with 5 mg/L of nitrate or even lower is associated with higher risks of colorectal cancer and adverse birth outcomes, such as neural tube birth defects.[4]

How We Conducted the Study

The data for nitrate testing of drinking water came from the 10 states’ government agencies that record data from required tests of public water systems. For example, we received Iowa’s data from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources and California’s data from the California State Water Resources Control Board. Through public records requests, we received all finished water nitrate tests conducted at each community water system in each state between 2003 and 2017, except for Oklahoma, for which we received nitrate tests for 2007 to 2017 only. Many of these test results can be found in EWG’s Tap Water Database.[5] We chose 2003 as the earliest date in our analysis for nine of the states, because all had nitrate testing data going back to 2003.

We analyzed the data for all community water systems that the Environmental Protection Agency considered active as of April 2019 and that conducted at least one test for nitrate between 2003 and 2017 for the nine states, and 2007 and 2017 for Oklahoma. We analyzed nitrate tests that had an EPA Safe Drinking Water Information System contamination code of 1040 for California, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin but used contamination code 1038 for Nebraska and Oklahoma.[6] The dataset included systems that use either groundwater or surface water as their main source of drinking water.

Public water systems are either community or non-community systems. Community water systems typically serve residents in cities and towns year-round – they are what most people think of as municipal systems or water utilities. Non-community systems serve sites like churches and schools with their own source of drinking water, and serve much smaller populations, usually for only part of the year. In this analysis we studied community water systems only, since they serve considerably more people than non-community systems.

We then narrowed the list of active community water systems that tested for nitrate to those with elevated nitrate. A system was considered to have elevated nitrate if it had at least one test at or above 3 mg/L at any time between 2003 and 2017. The level of 3 mg/L was chosen to represent elevated nitrate because the EPA considers 3 mg/L in groundwater used for drinking water an indication of contamination above naturally occurring levels.[7]

For some of the analysis, we also looked at how many systems had at least one test at or above 5 or 10 mg/L, since 10 mg/L is the legal limit of nitrate in public drinking water, and 5 mg/L is associated with negative health outcomes. We took out all exceptionally high nitrate tests that were above 100 mg/L, since we deemed these to be errors and not actual test results.

Once we established the group of community water systems with elevated nitrate – those with at least one test at or above 3 mg/L – we analyzed whether their nitrate tests increased, decreased or stayed the same between 2003 and 2017 (between 2007 and 2017 in Oklahoma). This was done by evaluating whether nitrate tests were correlated with year.

For each community water system, a correlation coefficient, or r value, was calculated to see whether nitrate positively or negatively correlated with year. Correlation coefficients describe the relationship between the two variables: Positive r values that are close to +1 show a strong relationship between year and increasing nitrate, and negative r values close to -1 show a strong relationship between year and decreasing nitrate.

Nitrate levels had increased in those community water systems that had a positive correlation, an r value above zero. Nitrate levels had decreased in systems with a negative correlation, an r value below zero. A few systems had zero correlation, which means their nitrate levels neither increased nor decreased over time. The summary report focuses on all systems with a positive correlation.

After finding the correlation coefficients for every system with elevated nitrate, we calculated the t and p values for each system.[8] These indicators determine whether the increase or decrease in nitrate over time was statistically significant. If the correlations at each system were statistically significant, that meant the increase or decrease in nitrate was not just a random increase or decrease.[9] We evaluated statistical significance at a 95 percent confidence level (p<=0.05).

Besides studying whether each community water system’s nitrate levels increased or decreased between 2003 and 2017, we also looked at whether the overall annual nitrate average across all elevated systems went up over time. (Test results reported as “non-detects” were assigned a value of zero.) We did this by calculating the average of annual tests for all systems with elevated nitrate between 2003 and 2017 by state, and then the growth rate in nitrate averages from year to year. The average across all the years’ growth rates provided the annual average growth rate for all elevated systems in each state, which was the average increase in the nitrate average in one year. The sum of all the annual growth rates in nitrate averages across the time period gave the overall growth rate in nitrate levels from 2003 to 2017, by state.

Contamination in smaller community water systems was more likely to get worse between 2003 and 2017. To figure out whether more systems with increasing nitrate levels over time were small or large, systems were put into EPA-designated size categories based on how many water customers each system served.[10] Very small community water systems serve 501 people or fewer; small systems serve between 501 and 3,300; medium systems between 3,301 and 10,000; large systems between 10,001 and 100,000; and very large systems serve over 100,000 people.

People in rural areas are also more likely to experience worsening nitrate contamination. To determine this, we put the location of each community system onto a map with 2010 U.S. Census Bureau–designated urban areas. The census delineates an “urban area” as one of two things, “urbanized areas (UAs) that contain 50,000 or more people and urban clusters (UCs) that contain at least 2,500 people.”[11] If a community water system was located in a U.S. Census Bureau–designated urban area, it was considered an urban system, and if not, it was considered a rural system.

Detailed Results

Between 2003 and 2013, 14,276 community water systems that provided water for approximately 104 million people in California, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin tested their finished drinking water for nitrate at least once. (The population listed for the systems was 104,395,379, but population listed for community water systems can be imprecise.) Of those, 28 percent had at least one test at or above 3 mg/L; 19 percent had at least one test at or above 5 mg/L; and 7 percent had at least one test at or above 10 mg/L (Table 1).

Table 1. Percent of Active Community Water Systems That Had at Least 1 Test at or Above 3, 5 or 10 mg/L, by State

|

State

|

Percent of systems with at least 1 test >=3 mg/L

|

Percent of systems with at least 1 test >=5 mg/L

|

Percent of systems with at least 1 test >=10 mg/L

|

|

California

|

44%

|

31%

|

12%

|

|

Illinois

|

18%

|

13%

|

3%

|

|

Iowa

|

27%

|

19%

|

5%

|

|

Kansas

|

61%

|

46%

|

17%

|

|

Maryland

|

32%

|

19%

|

5%

|

|

Nebraska

|

65%

|

53%

|

26%

|

|

Oklahoma

|

38%

|

27%

|

12%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

36%

|

23%

|

5%

|

|

Texas

|

8%

|

5%

|

2%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

30%

|

18%

|

5%

|

|

Total

|

28%

|

19%

|

7%

|

For systems with at least one test at or above 3 mg/L, 52 percent, or 2,111 community water systems, had increasing nitrate levels over time. California, Kansas and Texas had the highest percentage of communities with worsening nitrate contamination at 57 percent (Table 2).

Table 2. Community Water Systems With at Least 1 Test at or Above 3 mg/L That Had Increasing or Decreasing Nitrate Over Time, by State

|

State

|

Number of increasing systems

|

Percent of increasing systems

|

Number of decreasing systems

|

Percent of decreasing systems

|

|

California

|

669

|

57%

|

503

|

43%

|

|

Illinois

|

118

|

54%

|

95

|

44%

|

|

Iowa

|

126

|

53%

|

106

|

45%

|

|

Kansas

|

203

|

57%

|

154

|

43%

|

|

Maryland

|

77

|

54%

|

66

|

46%

|

|

Nebraska

|

159

|

46%

|

187

|

54%

|

|

Oklahoma

|

110

|

50%

|

107

|

49%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

266

|

41%

|

379

|

59%

|

|

Texas

|

218

|

57%

|

165

|

43%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

165

|

54%

|

136

|

45%

|

|

Total

|

2,111

|

52%

|

1,898

|

47%

|

Of the systems with increasing levels of nitrate contamination, 45 percent were statistically significant. However, of the 47 percent of systems where nitrate levels went down over time, only 41 percent decreased significantly. At 55 percent, California had the highest percentage of systems with increasing contamination that was statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3. Community Water Systems With at Least One Test at or Above 3 mg/L That Had Statistically Significant Increases or Decreases in Nitrate, by State

|

State

|

Number of systems with increase

|

Percent of systems with increase

|

Number of systems with decrease

|

Percent of systems with decrease

|

|

California

|

370

|

55%

|

235

|

47%

|

|

Illinois

|

35

|

30%

|

28

|

29%

|

|

Iowa

|

58

|

46%

|

50

|

47%

|

|

Kansas

|

97

|

48%

|

51

|

33%

|

|

Maryland

|

29

|

38%

|

18

|

27%

|

|

Nebraska

|

83

|

52%

|

88

|

47%

|

|

Oklahoma

|

30

|

27%

|

30

|

28%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

100

|

38%

|

176

|

46%

|

|

Texas

|

93

|

43%

|

61

|

37%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

64

|

39%

|

42

|

31%

|

|

Total

|

959

|

45%

|

779

|

41%

|

Figure 1 provides the annual nitrate averages by state between 2003 and 2017 for all systems with elevated nitrate contamination – at least one test at or above 3 mg/L – that had worsening nitrate over time. Oklahoma’s annual nitrate averages were only between 2007 and 2017.

Figure 1. Average Annual Nitrate for Community Water Systems With Increasing Nitrate Between 2003 and 2017, by State

When looking at average nitrate levels for communities with worsening nitrate, Wisconsin had the largest increase in nitrate between 2003 and 2017 at 46 percent. Kansas had the smallest growth rate over those years, but its nitrate averages grew 17 percent in that time nonetheless (Table 4).

Table 4. Growth Rate in Nitrate Averages Between 2003 and 2017 for the Community Water Systems With Increasing Nitrate, by State

|

State

|

Percent increase in nitrate averages between 2003 and 2017

|

|

California

|

31%

|

|

Illinois

|

43%

|

|

Iowa

|

29%

|

|

Kansas

|

17%

|

|

Maryland

|

26%

|

|

Nebraska

|

28%

|

|

Oklahoma

|

44%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

37%

|

|

Texas

|

21%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

46%

|

Nitrate contamination is more likely to get worse for people living in rural areas. At 86 percent, Nebraska had the highest percentage of increasing nitrate systems located in a rural area (Table 5).

Table 5. Percent of Increasing Nitrate Community Water Systems Located in a Rural Versus Urban Area, By State

|

State

|

Percent rural

|

Percent urban

|

|

California

|

37%

|

63%

|

|

Illinois

|

62%

|

38%

|

|

Iowa

|

73%

|

27%

|

|

Kansas

|

79%

|

21%

|

|

Maryland

|

34%

|

66%

|

|

Nebraska

|

86%

|

14%

|

|

Oklahoma

|

79%

|

21%

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

46%

|

54%

|

|

Texas

|

69%

|

31%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

65%

|

35%

|

|

Total

|

57%

|

43%

|