Toxic pollution from industrial-scale poultry farms – hundreds of thousands of tons of manure from millions of chickens – threatens the rivers and streams of northeastern Oklahoma.

But as Oklahoma’s attorney general, Scott Pruitt – President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee to head the Environmental Protection Agency – rolled back efforts to protect the waters of his home state from the poultry industry and other polluters.

As the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee prepares to hold Pruitt’s confirmation hearing this week, an EWG investigation of his record “defending” the environment in Oklahoma shows:

- Pruitt declined to pursue his predecessor’s lawsuit against poultry polluters, which would have kept chicken manure from fouling a state-designated scenic river.

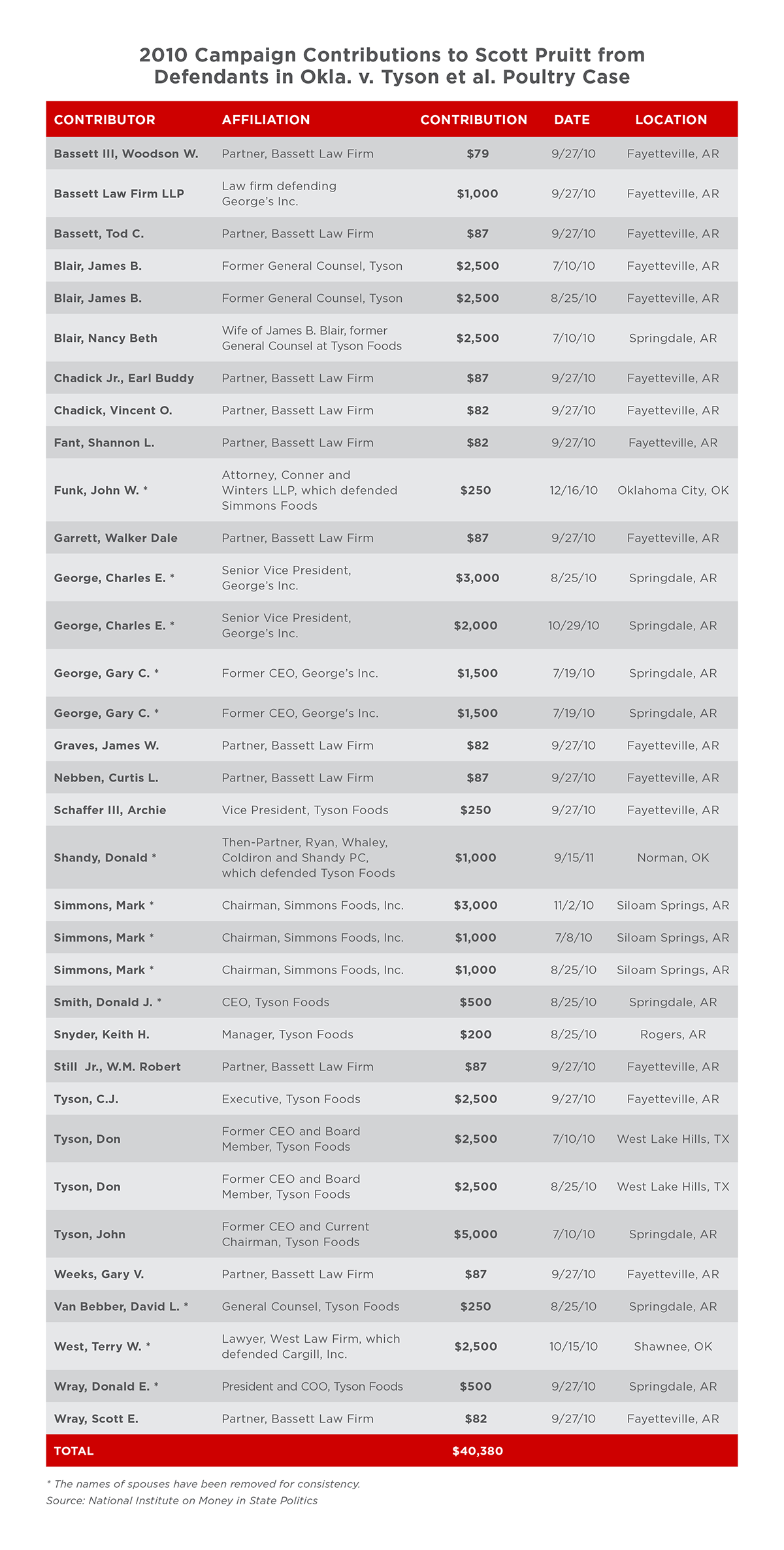

- Many of the poultry polluters named in the suit contributed heavily to Pruitt’s 2010 campaign for attorney general.

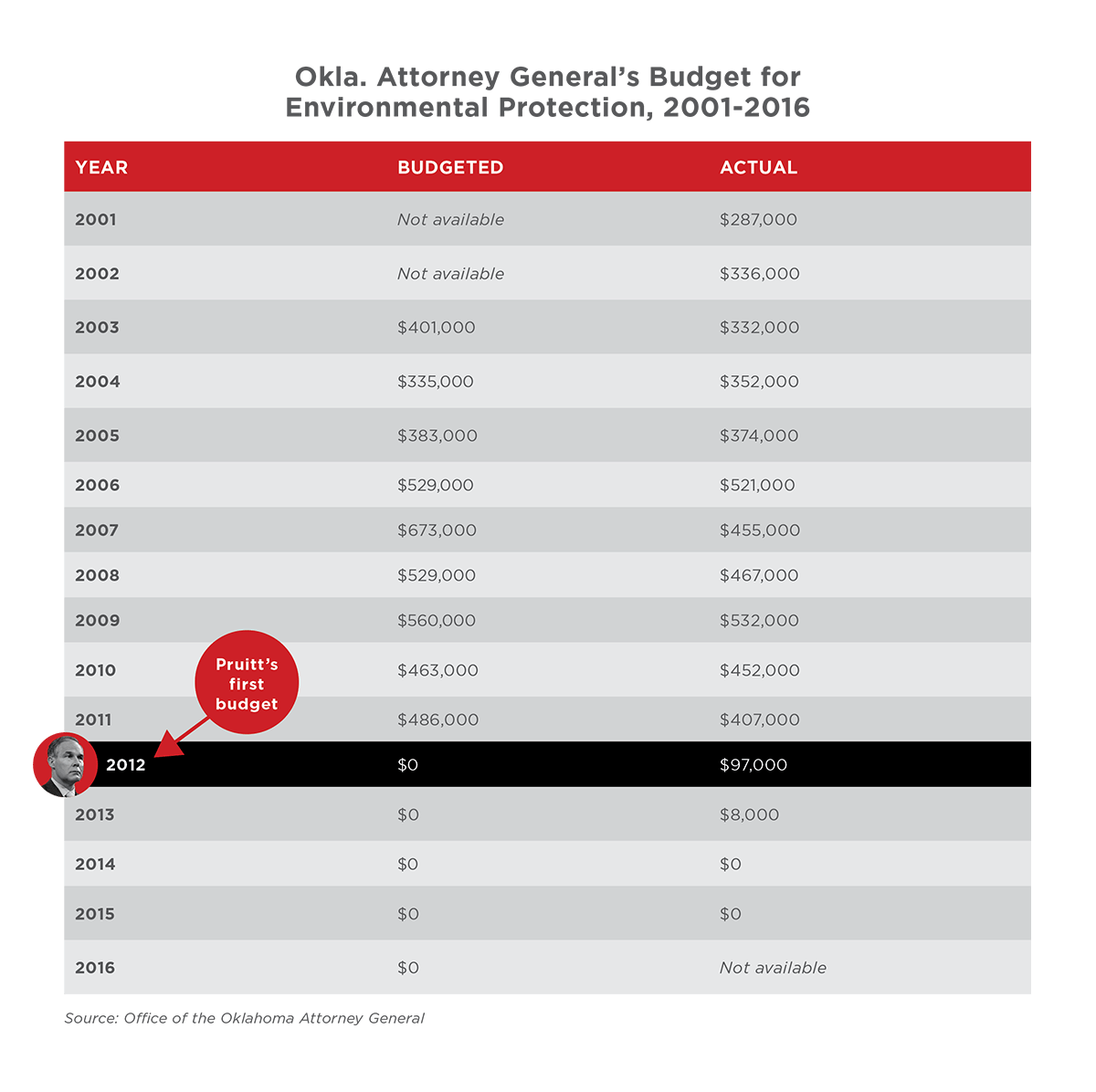

- Before Pruitt took office, the Environmental Protection Unit of the attorney general’s office took on factory chicken farms over water pollution. After Pruitt was elected, he disbanded the unit.

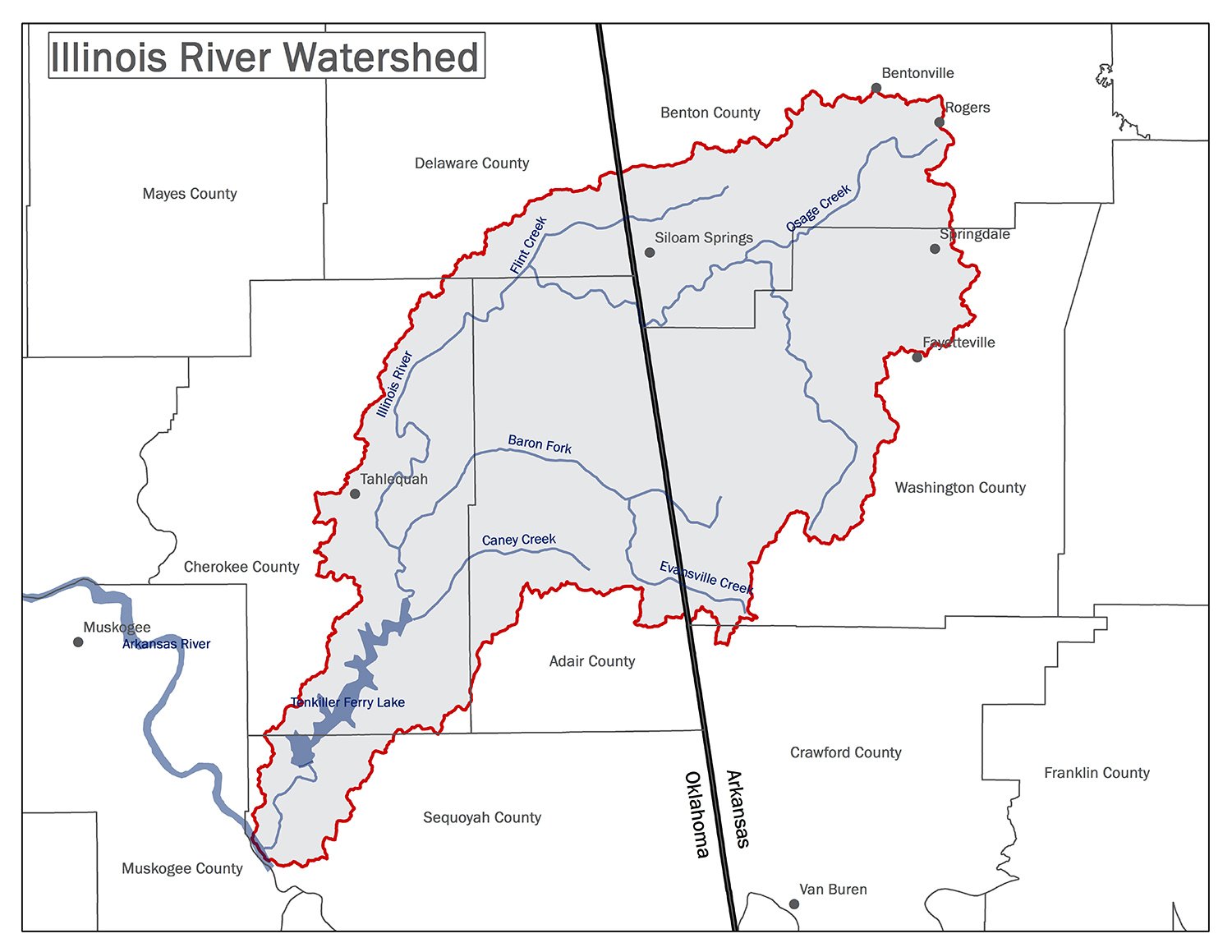

The Illinois River, which flows into the state from Arkansas, is designated for special protection by Oklahoma as a scenic river, and the river's basin is classified as highly vulnerable to groundwater pollution. In 2005, Pruitt’s predecessor, former Attorney General Drew Edmondson, filed a lawsuit in federal district court to stop Tyson Foods and other poultry companies in the Illinois River basin from spreading massive amounts of chicken manure on land that ran off into nearby waters.

Arguments in the lawsuit concluded the year before Pruitt took office as the state’s top law enforcement official, but the judge in the case has inexplicably failed to issue a ruling. In his six years in office, Pruitt did not push for a resolution. In 2015 he told The Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper: “Regulation through litigation is wrong in my view. That was not a decision my office made. It was a case we inherited.”

But Pruitt had no such qualms about bringing lawsuits against the same agency he has been nominated to head. He filed or supported more than a dozen lawsuits designed to block EPA efforts to protect air and water. He also joined efforts to weaken clean water rules governing animal waste in other states and to roll back animal welfare protections. Pruitt even found time to issue a bogus “consumer alert” to try to intimidate the Humane Society of the United States, an action the group successfully challenged in court.

Pruitt may be opposed on principle to “regulation through litigation,” but contributions to his campaign raise the question of a conflict of interest in his failure to pursue Edmondson’s lawsuit.

Records of campaign contributions show that executives of the poultry companies named in Edmondson’s lawsuit, and the companies’ lawyers, gave more than $40,000 to Pruitt’s 2010 campaign, with nearly 90 percent of those contributions coming from outside Oklahoma. Overall, nearly a tenth of Pruitt’s political contributions in 2010 came from food and agriculture interests.

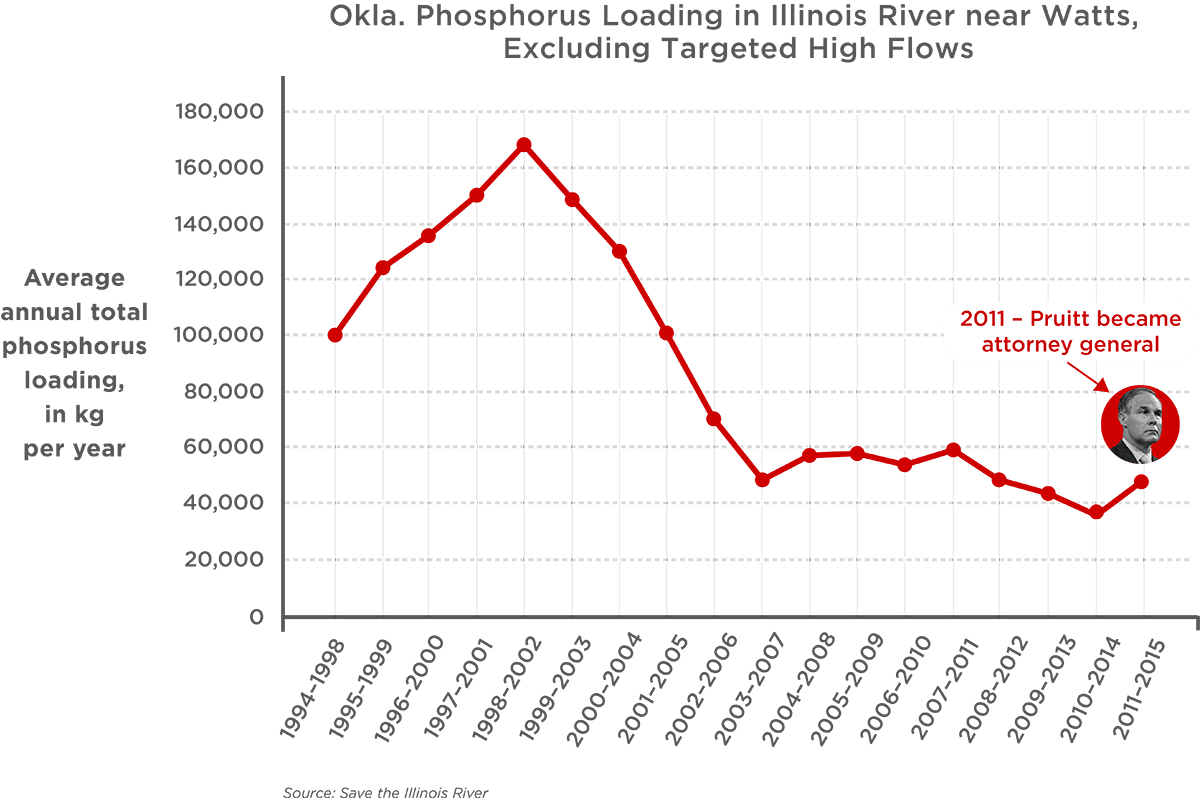

Between 1998 and 2010, Edmondson, the attorney general's Environmental Protection Unit, and state and local officials made important progress in cleaning up northeastern Oklahoma rivers and streams.

In 1998, legislators led by State Sen. Paul Muegge passed tough rules to address poultry pollution. In 2002, Gov. Frank Keating issued an emergency rule barring poultry operations from being built near rivers and in floodplains.

In 2003, Oklahoma and Arkansas officials reached an agreement to clean up the scenic Illinois River, which supports a $9 million recreation industry. The City of Tulsa successfully sued poultry polluters for fouling the city’s water supply with chicken waste.

Progress was partly the result of mandatory plans to limit the amount of poultry manure that can be used as fertilizer and to ship excess waste out of the Illinois River watershed. As a result, levels of phosphorous, a poultry waste pollutant that triggers toxic algae blooms, fell by more than 40 percent.

But that progress stopped after Pruitt was elected Oklahoma attorney general. The year before he was elected, the Environmental Protection Unit’s annual budget was $532,000. After that it declined steadily, then sharply, until it reached zero in 2014. Currently, the attorney general’s website does not list a unit dedicated to environmental protection or enforcement.

Pruitt claims that he helped broker a 2013 amendment to the 2003 Illinois River agreement between the states of Oklahoma and Arkansas. But the 2013 amendment was a delay tactic which primarily required an additional study to reassess the targets set seven years before he was elected and to suspend enforcement.

If Pruitt is confirmed as EPA administrator, among the first decisions he will make is whether to approve a new anti-pollution budget for the Illinois River – among many other polluted rivers, lakes and bays – and whether to preserve other rules that protect drinking water. His record does not inspire confidence that he will put public health before the interests of polluters.