Jump to:

.jpg?h=2e181f1f&itok=7sAvC5Qw)

Jump to:

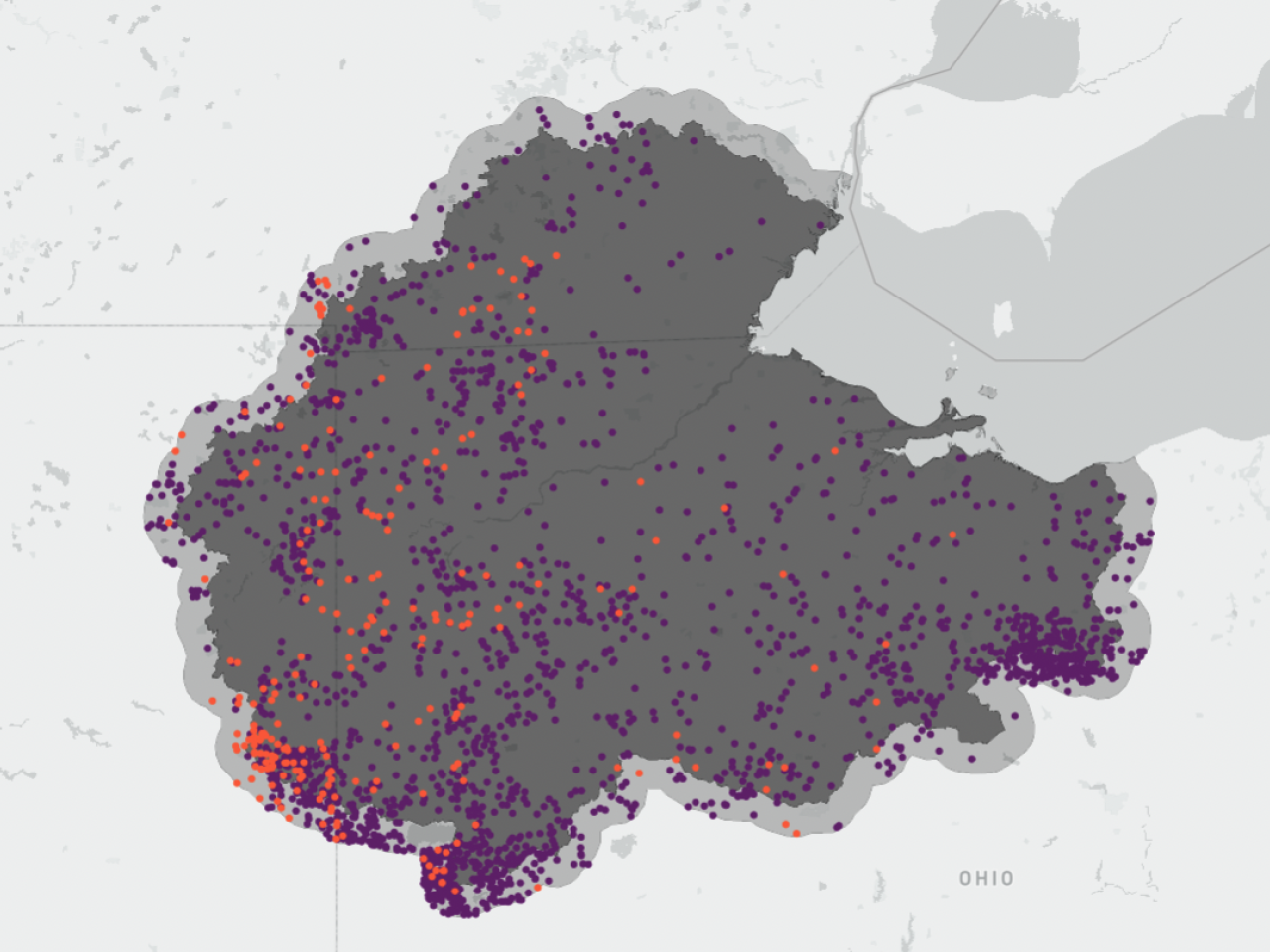

A new EWG analysis has identified and mapped more than 2,500 animal feeding operations in the Western Lake Erie Basin, a watershed encompassing nearly 6 million acres in Indiana, Michigan and Ohio that drains into Lake Erie, which has a well-known toxic algae bloom every summer. These facilities house about 400,000 cows, 1.8 million hogs and nearly 24 million chickens and turkeys.

Until now, no one has known where all the facilities in the basin are located or what’s happening to the massive amounts of manure the animals produce. That’s because states and the federal government only track the largest factory farms, which are called confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, and require a permit to be built.

Operations whose size falls below a certain threshold are not required to get state or federal permits, and once they’re up and running, their owners don’t need to account for the waste the animals produce – or where it goes.

We found over 2,200 unpermitted facilities in the Western Lake Erie Basin – 90 percent of all animal operations in the watershed. And though these operations are smaller than permitted CAFOs, collectively they produce most manure in the basin.

The most common way to dispose of livestock manure is to apply it to cropland as a fertilizer, typically with commercial fertilizer. The manure is largely managed in a liquid form – a combination of feces, urine and water – so it is heavy and costly to transport. That means manure is usually applied to fields close to where it is produced, most often within a few miles.

EWG’s report and map pinpoint hot spots in the Western Lake Erie Basin with high densities of animal agriculture operations, from small to large facilities. Our calculations show that, in several of these places, there is likely not enough cropland near operations to absorb the massive amounts of nutrients – primarily nitrogen and phosphorus – in the manure all these animals produce. So some of the algae-bloom-feeding phosphorus that manure contains is almost certainly running off farm fields and into nearby waterways.

This report builds on our groundbreaking 2019 report spotlighting how manure from mostly unregulated animal feeding operations in the Maumee River Basin contributes significantly to pollution in the Maumee River and western Lake Erie. By extending our analysis to the entire Western Lake Erie Basin, including a 5-mile buffer, the new report provides a more complete picture of the livestock facilities whose manure contributes phosphorus to Lake Erie.

EWG’s report and maps vividly illustrate how thousands of permitted and unpermitted animal feeding operations are contributing to water pollution issues in Lake Erie and beyond. And by shining a light on hot spots where facilities are particularly dense, we’re hoping to help state agencies in Indiana, Michigan and Ohio determine where to focus efforts to better track and manage these facilities and the enormous quantities of manure they produce and apply to crops.

Animal facility hot spots threaten human health and water quality

Many of the basin’s animal agriculture hot spots are miles away from Lake Erie, but nutrient runoff from crop fields can seep into the streams and rivers that eventually make their way downstream, feeding the annual algae bloom and posing a risk to the millions of people who rely on Lake Erie as a source for drinking water and recreation. The risk of runoff increases during severe storm events, which will happen with increasing frequency as the climate crisis accelerates.

Other algae blooms within the Western Lake Erie Basin are also fed by agricultural runoff. EWG’s map shows that the area near Grand Lake St. Marys, Ohio, is an animal feeding operation hot spot. The lake has had toxic algae blooms for many years, and this year a bloom had already appeared in May.

Toxic algae is not the only problem caused by excess manure and fertilizer. Polluted runoff containing nitrate gets into drinking water, leading to public health problems. Animal manure contains fecal coliform bacteria like E. coli, which can cause gastrointestinal sicknesses when it gets into drinking water in private wells. And livestock facilities also emit air pollutants such as hydrogen sulfide, ammonia and particulate matter that cause health problems like respiratory issues in nearby communities.

These problems are well known: The American Public Health Association issued a statement in 2019 urging a halt to all new or expanding factory farms due to the damage they inflict on public health.

Regulators do not track most animal operations in the Western Lake Erie Basin

For this report, we expanded our spatial footprint to the entire 11,870-square-mile Western Lake Erie Basin, scouring aerial photography from the Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Imagery Program to find unpermitted operations and using state records for permitted facilities.

Manure from both permitted and unpermitted facilities is applied to cropland as a fertilizer. Since manure is expensive to transport, most is applied to cropland within 5 miles of animal feeding operations. So manure applied in the basin may be produced just outside of it. That’s why we included animal operations and cropland within 5 miles of the watershed’s border.

In total, EWG identified 2,519 total animal feeding operations, in and just outside the Western Lake Erie Basin, with about 400,000 cows, 1.8 million hogs and nearly 24 million poultry (chickens and turkeys).

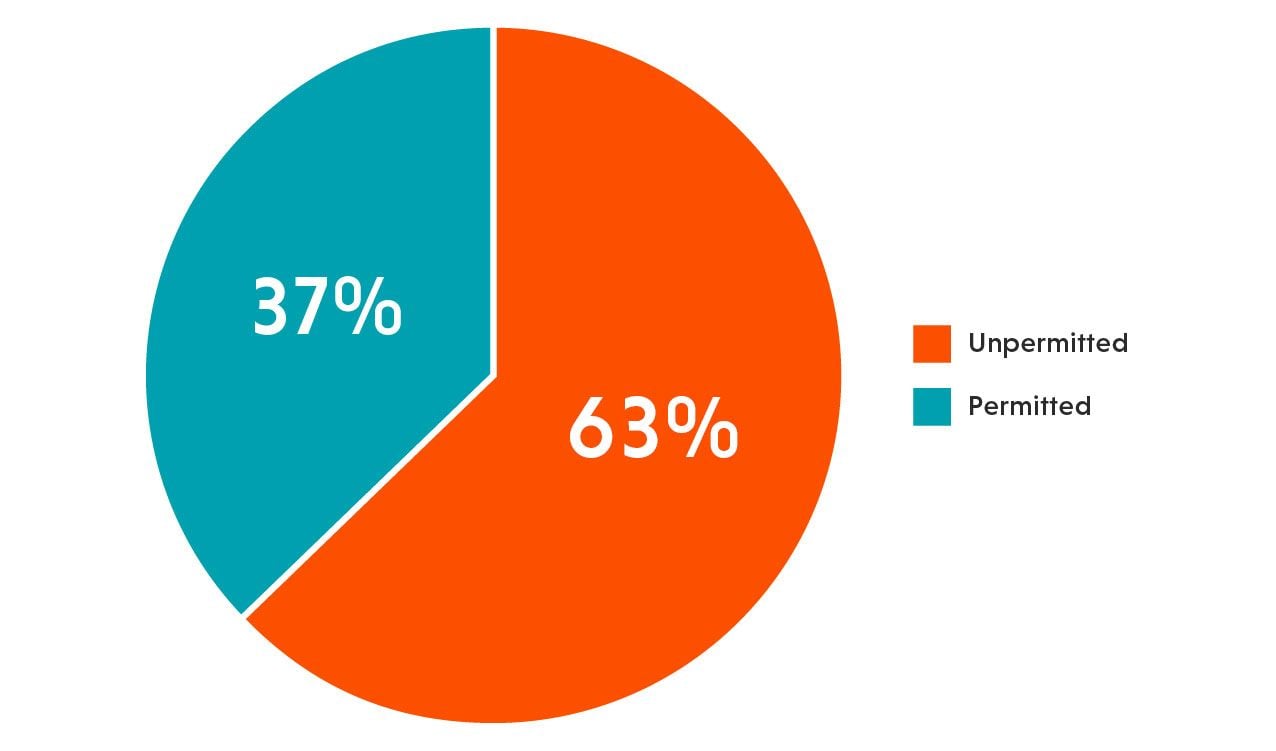

A total of 240 CAFOs were found to have permits from their respective states. Although permitted operations make up less than 10 percent of animal facilities, they account for 37 percent of the total phosphorus from manure produced in the basin.

The other 90 percent, or 2,279 operations, are unpermitted, and account for 63 percent of the manure phosphorus produced. State agencies have little to no information about these operations.

Figure 1. Permit status of manure phosphorus production.

Source: EWG via NAIP aerial photography, ODA, EGLE, IDEM and Midwest Plan Service.

Indiana has the highest percentage of permitted operations, 22 percent, because the state requires smaller facilities to have a permit. By contrast, only 13 percent of operations are permitted in Michigan and just 6 percent in Ohio, because these states make only the largest operations get a permit, as required by the Clean Water Act.

Of the 2,519 permitted and unpermitted animal feeding operations, over half – 59 percent – house either dairy or beef cows. Two-thirds of these operations are considered small, housing fewer than 200 cows.

Just 11 percent of cattle operations are considered large, housing more than 500 cows, but these operations, mostly large dairies, account for over one-third of total phosphorus from manure. Beef and dairy cows from operations of all sizes account for 56 percent of the phosphorus from manure applied to crop fields in the study area.

Hogs generate the next highest amount of manure phosphorus applied to crop fields, with 30 percent of the total. Poultry operations accounted for the least amount, at 14 percent, but these numbers are on the rise. EWG found that swine and poultry facilities had the largest growth in new operations in the Maumee River basin between 2005 and 2018.

Phosphorus is likely overapplied to fields in animal facility hot spots

EWG quantified the amount of manure produced by all animal feeding operations and mapped the likely locations of manure application to crop fields in and just outside the Western Lake Erie Basin.

For permitted operations, we relied on state records. For unpermitted operations, we used animal agriculture industry standards to analyze the footprint of each operation we found in aerial imagery and estimate the total number of animals housed and the amount of phosphorus-rich manure produced.

Crops take up phosphorus from the soil as they grow. The phosphorus is then removed from the system when the crops are harvested. EWG found that every year, an estimated 31,178 tons of phosphorus from manure is produced by all the livestock operations and applied to cropland within and just beyond the borders of the Western Lake Erie Basin.

EWG modeled manure application to over 200,000 crop fields to meet the phosphorus removal capacity of crops grown over the course of their rotation from 2015 through 2020. (See Methodology for more information.)

The total amount of phosphorus produced by animal feeding operations accounts for about 23 percent of the total amount of phosphorus removed by the nearly 6 million acres of cropland each year. This means that crops remove more phosphorus than is applied in manure each year, but localized areas of manure overapplication lead to phosphorus runoff.

The analysis revealed several distinct spatial areas where the risk of overapplication of manure phosphorus is high because of the density of animal feeding operations in these hot spots and inadequate cropland available for manure application. EWG found 116 animal feeding operations whose owners would need to go farther than 3 miles to find a field available for manure spreading without phosphorus overapplication, and 55 operations whose owners would need to go farther than 5 miles.

Manure potentially applied to crop fields surrounding animal feeding operations within the WLEB and a five-mile border

.jpg?itok=fBBEbzbr)

Source: EWG via NAIP aerial photography, ODA, EGLE, IDEM and Midwest Plan Service.

When assessing the availability of land for manure spreading by watershed, in 12 percent of subwatersheds, or 50 of 428, at least half the cropland in the subwatershed was required to avoid manure phosphorus overapplication between 2015 and 2020. In nine watersheds, more than 90 percent of the cropland was required. The most distinct of these livestock operation hot spots are located near the outer edges of the WLEB. In some areas, EWG found little risk of overapplication from manure.

Crops don’t just get phosphorus from manure. Commercial fertilizer containing phosphorus is also applied to farm fields. According to county-level estimates of phosphorus from commercial fertilizer from a 2021 U.S. Geographical Survey report, an estimated 94,065 tons of commercial phosphorus were sold in the study area in 2017. This means there is an even greater risk of overapplication of nutrients than that posed by manure alone.

What should be done

Regulated operations must go through a comprehensive analysis of nutrient inputs, but with two-thirds of manure phosphorus currently coming from unregulated facilities, not enough is being done to understand and manage the amount of manure being produced from all animal operations in and just outside the basin.

States must assess the amount of manure being produced by animal operations and the capacity of available land areas to handle an increasing manure nutrient load. Our analysis reveals a high level of spatial variability, as well as numerous areas with an elevated risk of nutrient runoff from manure application.

Important tactics for operations of all sizes to use to prevent nutrient runoff include better management of manure waste, sufficient space for grazing animals, prevention of livestock getting into streams and application of manure at recommended rates and timing.

Additionally, farmers in animal feeding operation hot spots should implement conservation practices on crop fields that are most likely to experience phosphorus runoff. For example, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy and the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development are working with farmers in the Western Lake Erie Basin to get targeted conservation practices on farm fields in the areas where they would have the biggest impact on reducing phosphorus runoff. More such programs should be implemented and prioritized by the basin states.