A single enormous cattle feeding operation potentially threatens the safety of thousands of acres of leafy greens grown in the U.S. during the colder months, an EWG analysis shows.

Irrigation water or dust contaminated with fecal matter from this giant feedlot, located in Yuma County, Ariz., could contaminate many acres of lettuce fields within 3 miles of the cattle farm, which produces 115,000 cows each year. This one feedlot is likely to be the source of contamination because of its size and proximity to the lettuce fields, compared to the other two animal feeding operations in Yuma County identified by the Food and Drug Administration in its investigations.

In a canal near this feedlot, the FDA also found the exact strain of the bacteria E. coli that sickened people from lettuce during a recent outbreak.

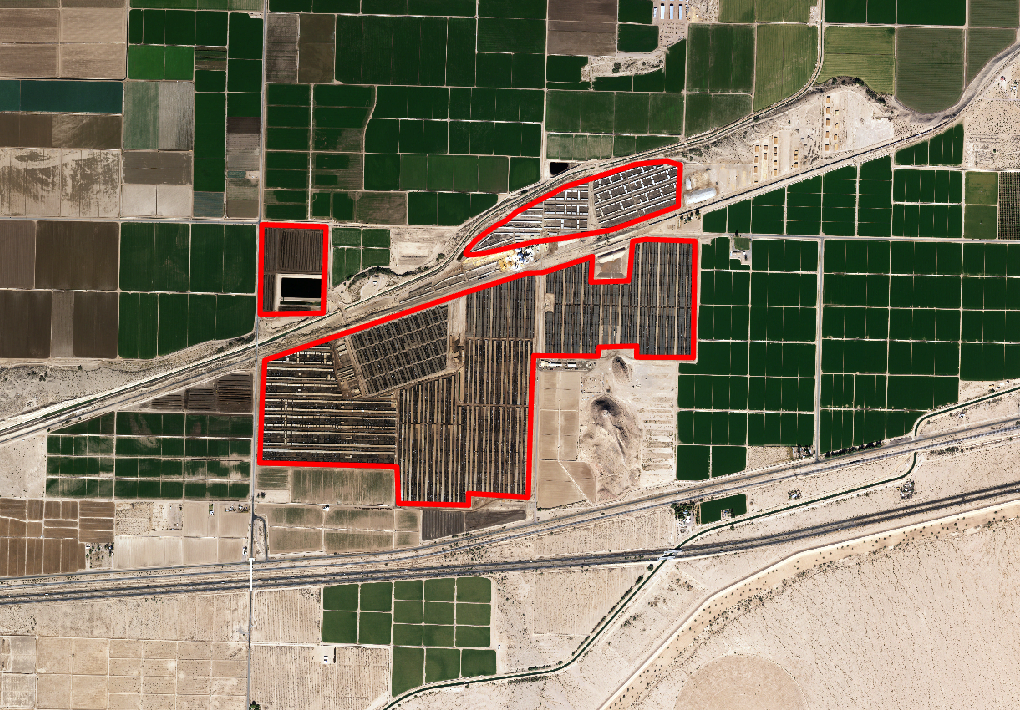

Farms in Yuma County that grow leafy vegetables produce 90 percent of the nation’s winter lettuce, between November and March. Among these farm fields is the 350-acre McElhaney Feedyard. (See image below; the cattle feedlot is outlined in red.) It is owned by the Five Rivers Cattle Feeding company, which owns cattle feedlots throughout the western U.S.

Source: EWG, from Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Imagery Program, 2021 imagery

Animal waste produced in a feedlot can contaminate nearby crop fields, like lettuce, with E. coli, a type of bacteria that can be found in the fecal matter of animals and humans. Most E. coli strains are harmless, but a few can make people extremely sick or lead to death.

Irrigation water in canals near animal feeding operations can become contaminated with E. coli and then sprayed on lettuce, or contaminated dust from feedlots can drift onto the lettuce fields. While cooking food can kill pathogens, lettuce is typically consumed raw, which makes E. coli contamination of leafy greens particularly dangerous.

Feedlot linked to previous outbreak

In 2018, five people died after eating romaine lettuce grown in the Yuma Valley. The FDA says the bacteria, which contaminated 36 lettuce fields on 23 farms in Yuma County, potentially came from the McElhaney Feedyard.

There were only three animal feeding operations in Yuma County when the FDA conducted its investigation into the 2018 outbreak. McElhaney Feedyard is the feedlot located closest to many acres of lettuce grown in this area. And the exact strain of E. coli on the lettuce that sickened and killed people was found by the FDA in an irrigation canal near this feedlot.

In late 2021, another outbreak of E. coli was linked to contaminated leafy greens, including kale and spinach. It sickened 10 people and killed one. That strain was the same as the one that caused the 2018 outbreak and was traced back to Yuma County, although the FDA did not seem to tie this one as closely to McElhaney Feedyard as it did the 2018 outbreak.

How E. coli spreads to leafy greens fields

There are two theories about how E. coli gets to lettuce and other leafy greens fields from animal feeding operations.

Bacteria from cattle manure may contaminate irrigation canals that travel past the feedlot, either through manure washing into the canals or from dust particles blowing from the feedlot into the canals through the air. Without knowing whether the water is contaminated, lettuce farmers use the water in the canals to irrigate their crops or mix it with pesticides before spraying it on the crops.

The FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention believe this is the most likely pathway of contamination for the 2018 and 2021 E. coli outbreaks.

Another theory is that E. coli–contaminated dust from feedlots drifts onto fields and settles on the leafy vegetables. While the federal health agencies prefer the irrigation canal theory, the possibility that contaminated cattle feedlot dust settles on farm fields is especially alarming, because particulate matter like dust can travel thousands of miles in the air.

In the new analysis, EWG finds that thousands of acres of leafy vegetables, including lettuce, are located within a short distance from the McElhaney Feedyard. An irrigation canal used by nearby farmers runs through the cattle feedlot, posing a risk of bacterial contamination of the leafy greens. EWG focused on this feedlot because the FDA found the strain of E. coli in lettuce that sickened people in the 2018 outbreak in an irrigation canal near this feedlot, and because of the canal’s proximity to lettuce fields, compared to the other two animal feeding operations in Yuma County identified by the FDA .

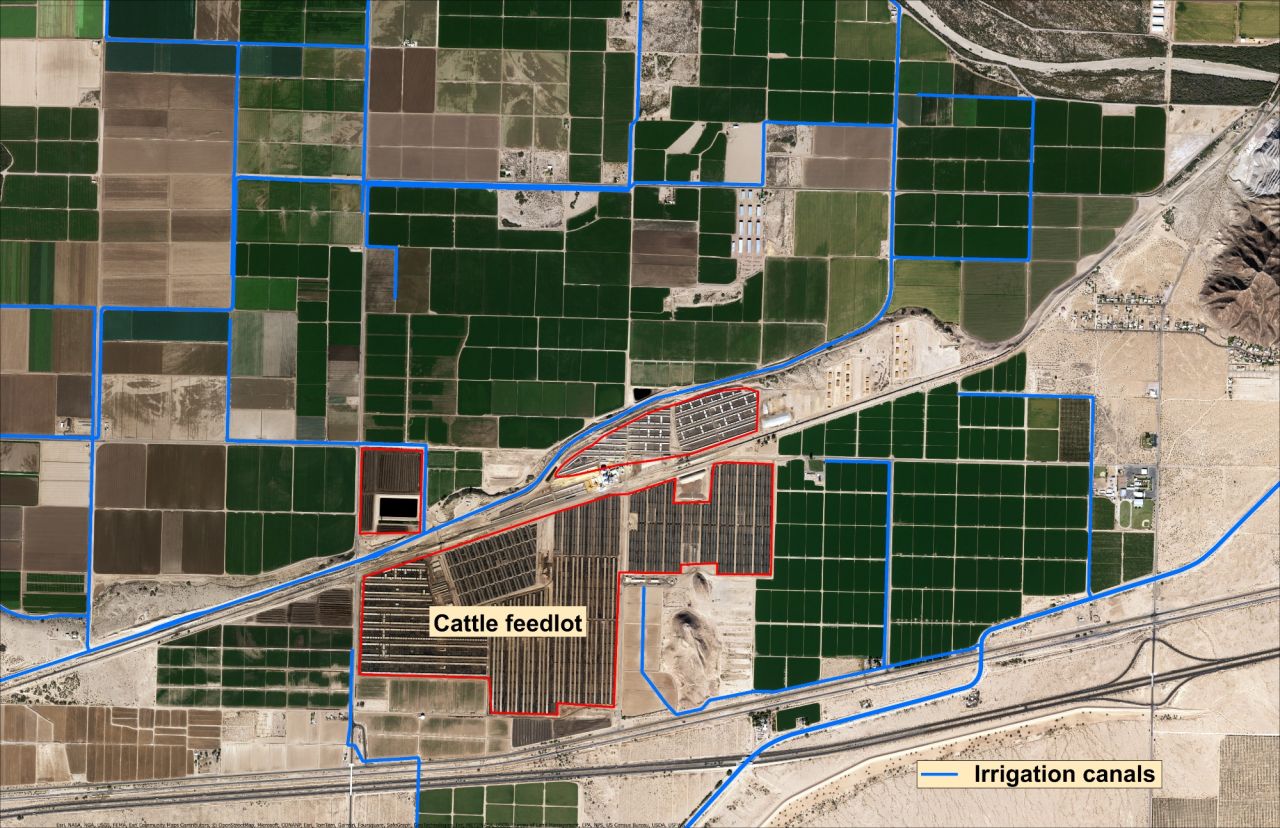

Many parts of the feedlot border a large irrigation canal. And as the image below shows, a pool of cattle manure and wastewater from the animal operation is even located within feet of an irrigation canal, making a spillover into the canal possible. (The canal is represented in the image by the blue line.)

Source: EWG, from Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Imagery Program, 2021 imagery

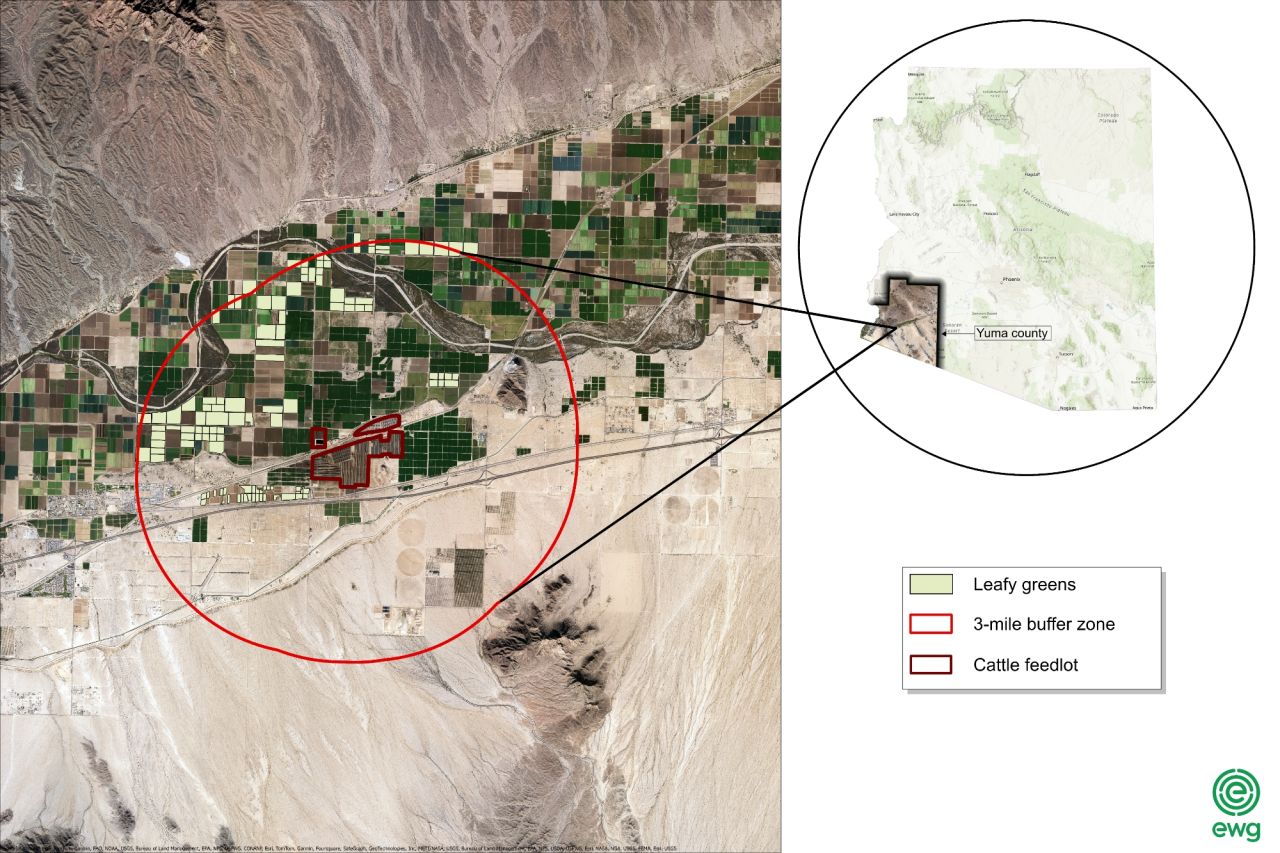

As the map below shows, the irrigation canal that runs through the feedlot is connected to many miles of other canals in the valley. So if E. coli from the cattle operation washes or blows into the irrigation canal, it can travel for many miles and may wind up on a large number of leafy vegetable fields. And the irrigation canal at risk ultimately drains into the Colorado River.

Source: EWG, from Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Imagery Program, 2021 imagery

Studies show that E. coli from cattle feedlots can drift in the air and land onto nearby farm fields. For our new analysis, EWG chose to look at a 3-mile buffer zone around McElhaney Feedyard to assess the number of acres of leafy greens fields, because research shows that 3 to 4 miles is the distance pollutants from animal feeding operations can travel by air and cause respiratory damage in residents.

The map below shows 1,899 acres of leafy greens, including lettuce, cabbage and herbs, within a 3-mile buffer zone of the feedlot. And the closest leafy vegetable field is only 938 feet away from the cattle operation.

Source: EWG, from Department of Agriculture National Agriculture Imagery Program, 2021 imagery

The proximity of the irrigation canal to the cattle feedlot and the fact there are thousands of acres of lettuce near the feedlot means an E. coli outbreak on leafy greens from Yuma County could happen again.

Inadequate regulation puts people at risk

Following a series of E. coli outbreaks caused by leafy greens, Congress in 2011 directed the FDA to develop standards for water sprayed on crops.

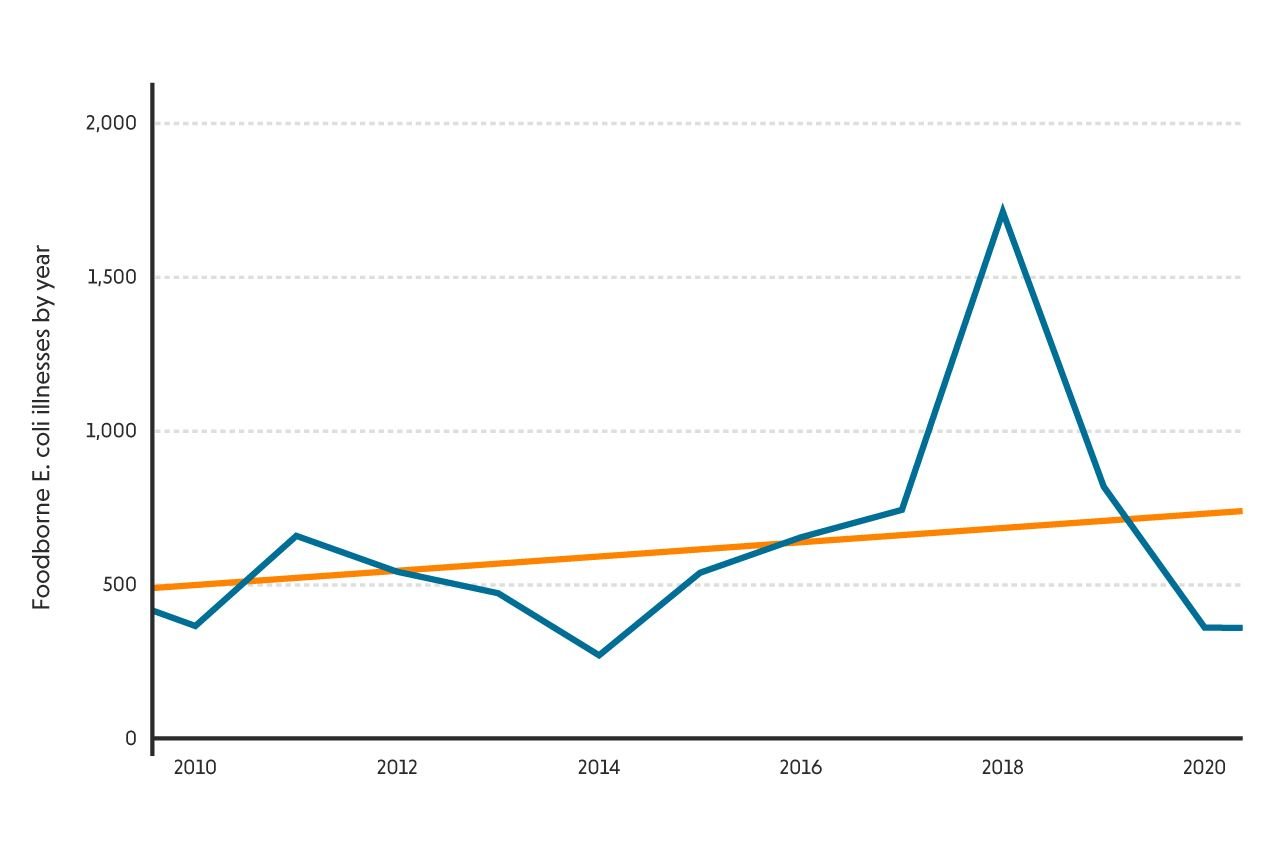

The rule the FDA first issued, in 2015, required enforceable periodic testing for contaminated irrigation water. But a revised rule, proposed in 2022, abandoned the requirement, allowing farms instead to decide whether to include tests in their “water assessments.” Voluntary efforts have not reduced the number of outbreaks, according to a CDC study. (Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Foodborne E. coli illnesses are still frequent in the U.S.

Source: EWG, from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Outbreak Reporting System

It is very difficult for consumers to protect themselves from E. coli in lettuce. The bacteria contaminate both organic lettuces as well as conventional ones, and studies show that washing lettuce before eating it does not significantly reduce E. coli, so there’s still a threat of getting sick.

The risk of contamination to food grown in the U.S. will continue unless farmers face stricter regulations to conduct tests of their irrigation water, management of manure from industrial agriculture is more rigorously monitored, and the FDA enforces its regulations more aggressively.

Methodology

For this analysis, EWG identified leafy greens fields within a 3-mile buffer of the McElhaney Feedyard in Yuma County, Ariz. The location of the feedyard was found through a visual search of aerial imagery, and a 3-mile buffer was placed around this animal facility.

Using a combination of the Department of Agriculture’s Common Land Unit data and the Cropland Data Layer, or CDL, we overlaid this 3-mile buffer zone with a footprint of all fields used to grow leafy greens. EWG included all fields the CDL claimed contain lettuces, cabbage and herbs, including double-cropped acres used to grow a leafy green during part of the year and a different crop during another part of the year.

EWG included in the analysis all fields the USDA says are used to grow leafy greens, except for smaller fields – less than five acres – because these may be falsely categorized as a leafy green.

To find a footprint of all the irrigation canals near the feedlot and the leafy greens fields, we used the National Hydrography Dataset, from the U.S. Geological Survey.

.jpg?h=827069f2&itok=jxjHWjz5)