A new investigation by the Environmental Working Group and Midwest Environmental Advocates finds that in nine Wisconsin counties, commercial fertilizer and animal manure are overapplied to farmland at rates that are causing a water pollution crisis in rural Wisconsin.

Nitrogen and phosphorus in manure and commercial fertilizer are essential crop nutrients, but they can contaminate drinking water sources when they leach into groundwater or run off farm fields.

These are the hard facts: In four counties, nitrogen from manure and fertilizer is applied at more than 50 percent above the rates recommended by University of Wisconsin scientists to minimize pollution. And phosphorus contamination from the two sources combined overloads lakes, rivers and streams in three of the nine counties.

The crisis shows no sign of abating – the number of confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in Wisconsin has dramatically increased over the past few decades. Livestock operations of all sizes are defined by Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, as animal feeding operations, or AFOs. The DNR further defines CAFOs as industrial facilities with more than 1,000 “animal units."

Wisconsin now has hundreds of CAFOs, even as the state lost 44 percent of its dairy farms over the past decade. Milk production in Wisconsin continues to grow and is now at record levels, driven by the dramatic rise in the number of CAFOs. An estimated 3 percent of Wisconsin farms now produce roughly 40 percent of the state’s milk.

And as CAFOs multiply and grow larger, they continue to pump out massive amounts of manure for disposal. This raises concerns about the environmentally safe disposal of manure in areas already grappling with contamination of surface and groundwater resources.

Combined contamination: A problem plaguing Wisconsin

More than 1,500 miles of streams and rivers, and 33 lakes, in the nine counties assessed have impaired waters due overwhelmingly to combined pollution from manure and commercial fertilizer.

And without better environmental oversight, there’s no end in sight.

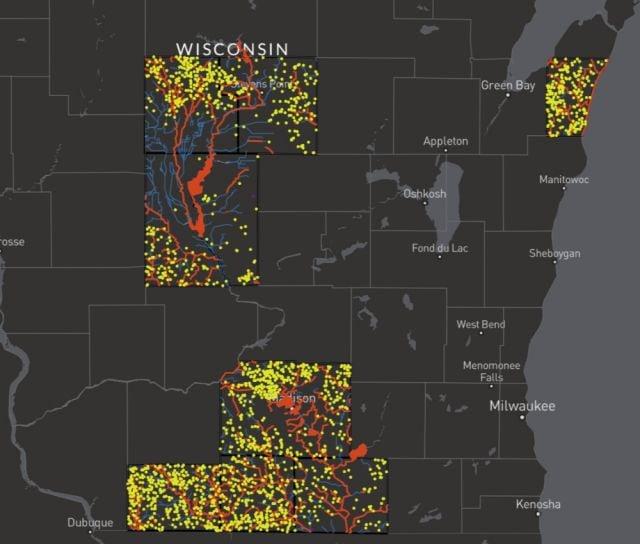

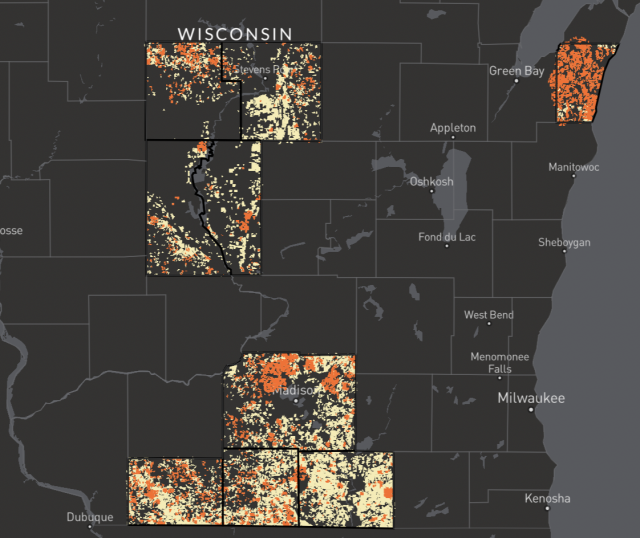

Using advanced geospatial techniques, we simulated and mapped every crop field within the nine Wisconsin counties likely to receive manure from nearby animal feeding operations. Detailed crop rotations for nearly 90,000 agricultural fields were used to determine how much, and where, manure nutrients were likely to be applied. We then added those amounts to the estimated nitrogen and phosphorus in the fertilizer sold in the county. (See the “Methodology” section at the end of this article for more information.)

The results indicate widespread overapplication of nutrients relative to UW recommendations about what’s needed for crops to thrive. In several areas, there’s not enough agricultural land to safely and economically dispose of the manure that animal feeding operations generate.

- In eight of the nine counties, nitrogen from manure and fertilizer sold exceeded UW recommendations. In four of the nine counties, nitrogen from the two sources surpassed UW’s recommendations by more than 50 percent.

- Commercial fertilizer sales alone exceeded UW nitrogen fertilizer application recommendations in five of the nine counties.

- County-level phosphorus balances fared slightly better, with phosphorus from manure plus phosphorus from fertilizer sold exceeding the total crop removal of phosphorus in three of the nine counties. Crops take up phosphorus from the soil as they grow; it is removed from the system when they are harvested.

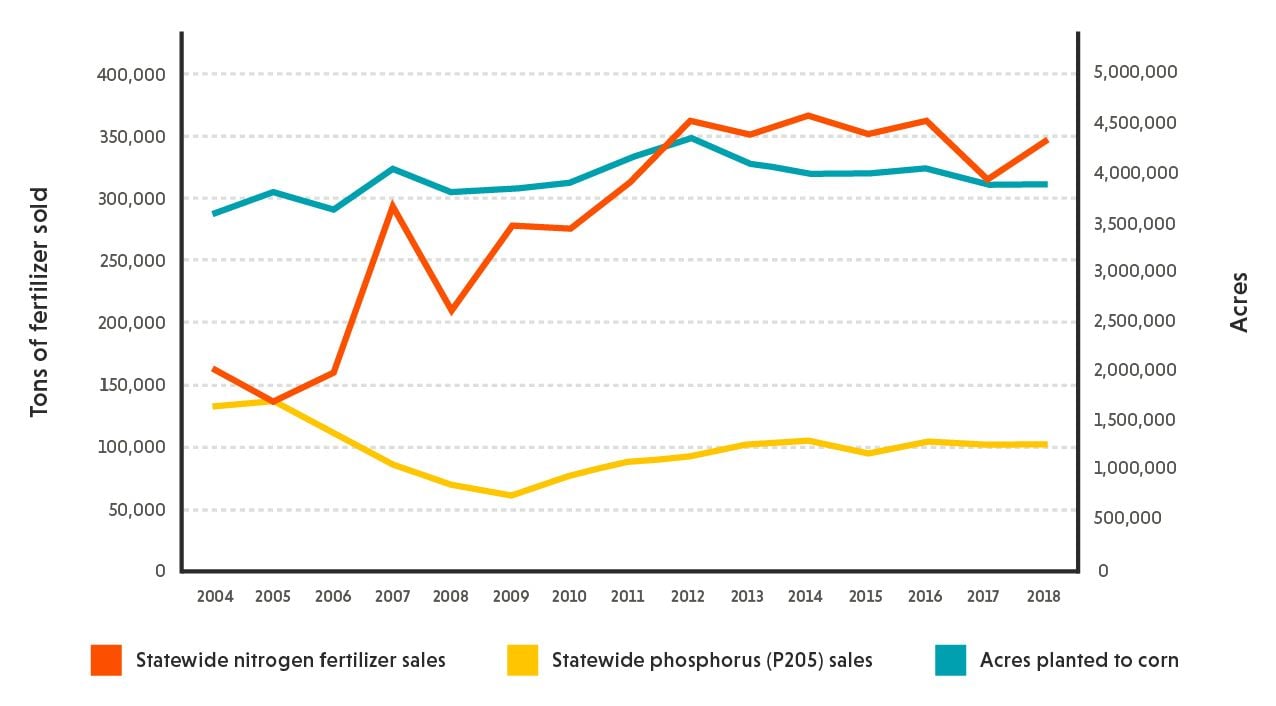

Commercial fertilizer sales in the state more than doubled in recent years, increasing from 161,000 tons sold in 2004 to 345,000 tons in 2018. Acres planted to corn have remained relatively stable, suggesting that more fertilizer is being applied to the same amount of land.

Figure 1. Commercial fertilizer sales in Wisconsin (2004-2018).

Source: EWG/MEA via Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection, USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Every year, nearly 20,000 tons of manure nitrogen and 17,000 tons of manure phosphorus, or P205, are collected from the 1,901 livestock operations of all sizes in the nine counties and applied to nearby crop fields.

An estimated two-thirds of manure nutrients in the counties are produced by unpermitted operations, for which the Wisconsin DNR has little to no information regarding location, size, how much manure they produce or where it is spread. To fill this enormous knowledge void, we spent months scouring aerial photography to locate non-permitted animal feeding operations and assign the type of animal they house and the size of each locations’ footprint.

Only 3 percent of the 1,901 operations are CAFOs, which the DNR permits, and for which manure storage and application are regulated. Large CAFOs account for less than 3 percent of the total number of operations, but these CAFOs house 25 percent of the cows and are responsible for a third of the manure produced and applied to cropland in the nine counties. All but 21 of the 1,901 operations house cattle, the vast majority of which – 83 percent – are dairy cows.

Table 1. Nitrogen balance from manure plus commercial fertilizer in nine Wisconsin counties.

|

County |

Percent N recommendation met by manure applied |

Percent N recommendation met by fertilizer sold |

Percent N recommendation met by manure and fertilizer combined |

Tons of N overload |

|

Adams |

11% |

144% |

156% |

3,026 |

|

Dane |

33% |

93% |

126% |

4,207 |

|

Green |

19% |

106% |

125% |

2,010 |

|

Juneau |

19% |

110% |

129% |

1,135 |

|

Kewaunee |

98% |

99% |

196% |

4,068 |

|

Lafayette |

21% |

90% |

111% |

1,167 |

|

Portage |

11% |

176% |

187% |

8,000 |

|

Rock |

7% |

93% |

100% |

31 |

|

Wood |

33% |

130% |

163% |

2,108 |

Source: EWG/MEA via Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection, University of Wisconsin Extension, USDA-ARS Agricultural Conservation Planning Framework.

Table 2. Phosphorus balance from manure plus commercial fertilizer in nine Wisconsin counties.

|

County |

Percent P205 removal met by manure applied |

Percent P205 removal met by fertilizer sold |

Percent P205 removal met by manure and fertilizer combined |

Tons of P205 overload |

|

Adams |

25% |

106% |

131% |

671 |

|

Dane |

48% |

42% |

90% |

-1,055 |

|

Green |

28% |

44% |

72% |

-1,619 |

|

Juneau |

33% |

53% |

86% |

-321 |

|

Kewaunee |

123% |

41% |

164% |

1,898 |

|

Lafayette |

39% |

41% |

80% |

-1,448 |

|

Portage |

22% |

105% |

127% |

1,230 |

|

Rock |

13% |

42% |

55% |

-3,843 |

|

Wood |

47% |

47% |

94% |

-155 |

Source: EWG/MEA via Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection, University of Wisconsin Extension, USDA-ARS Agricultural Conservation Planning Framework.

We simulated which fields could safely accept manure, based on distance from the animal feeding operation, the amount of nitrogen recommended by UW experts for crops and the phosphorus removed by growing crops.

An inherent problem with manure application is the imbalance between nitrogen and phosphorus relative to crop needs. When manure is applied to meet the nitrogen recommendation for crops, phosphorus is often overapplied. This leads to an accumulation of phosphorus in the soil and an increased likelihood of runoff over time.

Nitrogen is often the nutrient that drives manure and fertilizer spreading on Wisconsin cropland. Our analysis found that across the nine counties, 64 percent more crop acres are needed for manure to be applied without phosphorus overapplication. In several areas, this additional land is not available within a distance within which it is economically reasonable to haul manure.

In Wisconsin, manure is typically spread on agricultural fields close to where it is produced. This understanding is supported by a recent UW economic analysis, which noted that in 2010, manure applied to corn typically traveled 0.49 miles.

- In Kewaunee County, manure phosphorus alone exceeded total crop phosphorus removal in the county by 23 percent. This means the additional 1,222 tons of commercial phosphorus estimated to be sold in the county are unnecessary.

- In Dane County, 28 operations needed to travel more than 3 miles to dispose of manure generated without exceeding the phosphorus removal capacity of nearby crops.

UW manure spreading recommendations also allow producers to apply manure to crops such as alfalfa and soybeans, up to the rate at which they remove nitrogen.

CAFOs and smaller agricultural operations use this approach to dispose of manure by applying it to crops that likely do not need additional nutrients. This opens up more land for manure spreading, though UW Extension notes that the fall of the terminal alfalfa year has traditionally been a peak time for dumping excess manure.

We modeled manure application for three scenarios described in the interactive map below.

A void of important information

EWG and MEA’s analysis reveals a critical lack of publicly available data on the agricultural practices that are causing pollution in Wisconsin.

Nutrient management plans, or NMPs, are tools for animal feeding operations that guide the use of manure and fertilizers on crops. NMPs are not tools for protecting waters or public health, and though they may help with tracking or understanding sources of excessive nutrient application, extensive water contamination exists even in regions with relatively high NMP adoption.

CAFOs are required to have NMPs, and the state’s DNR reviews them during the water pollution discharge permitting process. Some counties or municipalities have adopted additional local regulations called Livestock Facility Siting Ordinances that give them the authority to independently review CAFO NMPs.

But only CAFO NMPs are subject to public review in that process. Most animal feeding operations are not permitted, so they are not legally required to have an NMP. They are not subject to the same level of oversight or enforcement from the DNR or local governments.

Knowledge of the location and size of all animal feeding operations that apply manure to crop fields is critical for understanding the risk of excess manure nutrients at a local level. Although we were able to identify sources of manure, there is no publicly available data on county-level commercial fertilizer sales or application in Wisconsin.

State-level fertilizer sales of both nitrogen and phosphorus provide the best data available. We apportioned statewide sales to each of the nine counties based on their respective percentage of statewide fertilizer and lime expenditures, as reported in the 2017 Agricultural Census.

The data gaps hinder state officials’ capability to take meaningful action toward addressing widespread nutrient pollution issues at the local level.

Public health, environment suffer

Overapplication of manure and commercial fertilizer is a double whammy that leads to excess levels of nitrogen and phosphorus and threatens public health and water resources in Wisconsin.

Nitrate is Wisconsin’s most widespread groundwater contaminant. Over the past two decades, nitrate contamination has consistently increased in extent and severity. Most of this nitrate pollution – more than 90 percent – comes from agricultural sources.

An estimated 8 to 10 percent of Wisconsin private wells currently exceeds nitrate levels of 10 milligrams per liter, or mg/L, a level that is known to cause blue baby syndrome in infants. And that number is estimated to increase by about 20 to 30 percent in predominantly agricultural areas. Many of these areas coincide with the counties included in this study.

Exposure to nitrate in drinking water at levels much lower than 10 mg/L also increases the risk of thyroid disease and colorectal cancer. A recent EWG and Clean Wisconsin analysis found direct medical costs for nitrate contamination of Wisconsin’s drinking water range from $23 million to $80 million per year.

Phosphorus contamination of lakes and rivers can trigger algae blooms and adversely affect the health of humans and aquatic organisms. In 2020, the DNR found phosphorus accounted for almost 50 percent of the impaired water listings in the state.

An estimated 17 percent of private water supply wells statewide have tested positive for total coliform bacteria, which indicates the presence of other biological agents from animal or human waste. A recent study of groundwater contamination in Kewaunee County concluded the primary factor of acute gastrointestinal illness in the county was cow manure.

Pause on CAFOs: A second look rural landscape capacity

Wisconsin has delegated authority to issue federal Clean Water Act permits, and therefore it must develop total maximum daily loads, or TMDLs, to try to reduce the input of pollutants that impair bodies of water in the state, such as nitrogen and phosphorous.

Within the nine counties analyzed, six are almost entirely within watersheds that are developing or have an EPA-approved TMDL for phosphorus impairments. TMDLs calculate phosphorus contribution from non-point sources, but the DNR does not have specific rules in place to change manure-spreading practices to limit phosphorus loading from those non-point sources.

County conservationists and local environment departments, already underfunded and understaffed, are tasked with overseeing agricultural operations and understanding the effects that animal waste and non-point source pollution may have on the land and water. But as nitrate and phosphorus accumulate and nutrients are transported outside the scope of county conservationist’s purview, they become harder to track and regulate.

The state’s efforts to curb nutrient contamination have been held up by legislative roadblocks. The DNR was poised to put new rules in place to curb nitrate contamination but abandoned the plan at the end of 2021, claiming the legislature had set deadlines for the regulation that were impossible to meet.

The rules would have limited nutrient application at certain times of the year and in especially vulnerable areas of the state, many of which are included in this analysis.

The continued proliferation of CAFOs will only exacerbate water quality problems in areas of the state included in this study and, likely, the rest of Wisconsin.

A comprehensive assessment of the capacity of Wisconsin's rural landscape to handle its manure and fertilizer load is essential to ensuring current and future residents have clean water. That assessment must drive decisions about whether to site new or expanded CAFOs – or lead to the conclusion that it’s time to close the door on new CAFOs so the state can tackle the double whammy of pollution.