Defenders of genetically engineered crops regularly claim that these varieties cut erosion by encouraging farmers to use tillage practices that enhance soil conservation.

These claims have been repeated so frequently they are now being taken at face value, but a closer look reveals the opposite: GE varieties have made little or no contribution to cutting soil erosion in the United States, and they pose frightening risks to soil and water quality. This Environmental Working Group analysis clearly shows that it was the conservation provisions of the 1985 farm bill, not planting genetically engineered corn and soybeans, that was responsible for a welcome reduction in soil erosion on cropland.

Some studies have suggested a link between adoption of GE varieties and conservation tillage, but the evidence for that linkage is weak. A recent (February 2014) report by USDA’s Economic Research Service did find that farmers growing GE varieties used conservation tillage practices more frequently than farmers planting conventional crops; but that correlation doesn’t mean adoption of GE varieties caused the increase in conservation tillage practices.

The adoption of herbicide-tolerant (HT) soybeans makes the strongest case for a cause-and-effect relationship with conservation tillage, but even there the evidence is weak. A 2013 study based on a computer model estimated that a 1 percent increase in use of herbicide-tolerant soybeans produced a minimal (0.21 percent) increase in conservation tillage.

Biggest drops in soil erosion happened before GE varieties were available

Cutting soil erosion is, of course, the reason we want farmers to adopt conservation tillage. Instead of taking yet another look at whether genetically engineered varieties encouraged conservation tillage, I decided to look for links between GE adoption and soil erosion. I didn’t find any.

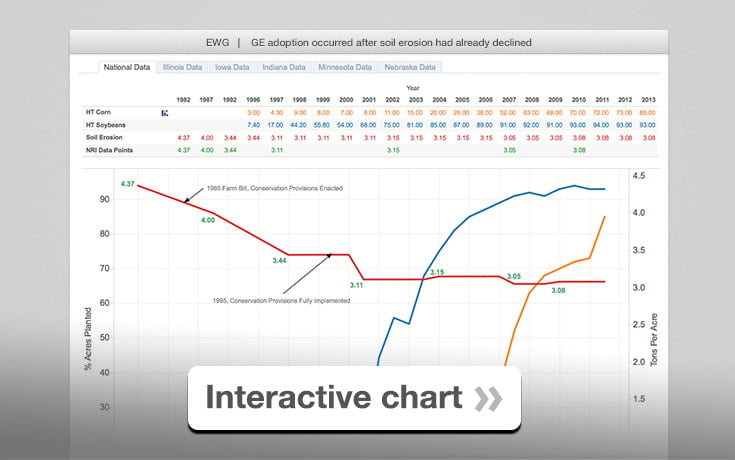

Figure 1 plots estimates of the rate of soil erosion made by USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (blue line) against the rate of adoption of herbicide-tolerant soybean and corn varieties (red and yellow lines). The steep drop soil erosion occurred before GE varieties were even on the market. As planting of the genetically engineered varieties soared, progress in soil conservation stalled.

Nothing in these data suggests that GE varieties have made any contribution at all to improving soil conservation in the United States.

What the data do convincingly show is that the credit for boosting soil conservation should go to the conservation provisions of the 1985 farm bill. The law Congress enacted established a quid pro quo between farmers and taxpayers. Farmers agreed to take steps to reduce soil erosion on their most highly erodible cropland in return for getting generous income subsidies at taxpayers’ expense. To qualify, farmers had to get their conservation practices in place between by 1985 and 1995 – the exact period when rates of soil erosion fell precipitously.

Figure 1: GE adoption occurred after soil erosion had already declined

Source: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Resources Inventory

USDA Economic Research Service, Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crop in the United States

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), also enacted in the 1985 farm bill, added to the progress between 1985 and 1995. The program paid farmers to take their most vulnerable land out of production and cover it with grass or other perennial vegetation. By 1995, 35 million acres of former cropland were enrolled in the program.

The best bet to boost progress in soil conservation is to ramp up implementation of the conservation compliance provisions in the current farm bill, which farmers must now meet to stay eligible for the bill’s incredibly generous crop insurance premium subsidies.

No link between GE crops and conservation in top five corn/soybean states

The national estimates of erosion in Figure 1 include soil lost from cropland planted with crops other than corn and soybeans. It’s conceivable that a drop in soil erosion on cropland planted with herbicide-tolerant corn and soybeans could have been swamped by an increase in erosion on other cropland. The top five corn and soybean states, however, show the same picture as the national data (Figures 2-6). Big cuts in soil erosion occurred before genetically engineered corn and soybean were available.

As adoption of GE varieties soared, moreover, progress in soil conservation stalled in Illinois, Indiana and Minnesota, and erosion actually increased in Iowa. Only Nebraska showed a decline in soil erosion between 1995 and 2010.

GE-spawned super weeds will lead to more erosion and polluted runoff

The notion that genetically engineered crops have contributed to soil conservation is a myth, but the risks that their use now poses to soil and water quality are frighteningly real. Weeds are becoming resistant to glyphosate, mostly applied in Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide. These so-called superweeds were spawned by overuse of the chemical on fields planted with herbicide-tolerant crops, mostly Monsanto’s own corn and soybean varieties. Farmers are resorting to more tillage and still more herbicides to keep them at bay – a recipe for accelerated soil erosion and polluted runoff.

Here, for example, is what Purdue University is recommending to farmers to combat glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth – the most dangerous of the new superweeds – in soybean fields:

- Rotate soybean fields with corn and/or plant a rye cover crop.

- Go back to deep tillage before planting, or burn down the field once or twice with tank mixes of two or three herbicides (glyphosate, 2,4-D, dicamba, gramoxone and/or metribuzin).

- Go back to residual herbicides applied before the crop is planted.

- Apply residual herbicides again in combination with burn-down herbicides after the crop has emerged.

- Hand weed if all else fails.

The genetically engineered crops that were promised to reduce the need for tillage and herbicides are instead leading to more tillage, more herbicides, more soil erosion and more polluted runoff. Pouring on more herbicides, particularly 2,4-D, is already spawning more weeds resistant to more herbicides, triggering a downward spiral that threatens public health, the environment and natural resources.

What started out as a myth is turning into a nightmare.