Everyone agrees: Permanently restoring hard-to-farm crop lands with trees and grasses that can act as carbon sinks is a good way to build soil carbon.

So why is the nation’s largest private lands conservation program failing to do so?

If we measure the success of a Department of Agriculture conservation program by its climate impact, the Conservation Reserve program, or CRP, is clearly failing.

Here’s why.

Building soil carbon to combat the climate crisis is a low priority for the CRP. Addressing climate change has not been the main goal of the program, but this needs to change.

After landowners offer to enroll their lands in the CRP through annual sign-ups, the USDA employs a tool, called the Environmental Benefits Index, or EBI, to decide which lands to accept.

But the EBI gives very little weight to carbon benefits. It gives much more weight to soil erosion and wildlife benefits. In the most recent sign-up, the USDA allotted just 10 points to the potential carbon sequestration benefits of land offered to the USDA – out of 395 points.

As a result, the lands with the most potential to build soil carbon are not being enrolled in the CRP. A scholar with the American Enterprise Institute recently concluded CRP acres are poorly targeted, if one of the CRP’s main goals is to combat the climate crisis. Other scholars have found giving greater weight to carbon sequestration in CRP enrollment would significantly change which acres of land are enrolled. One scholar speculates that a “Carbon Capture CRP” could produce more benefits than “much debated, currently unproven” carbon markets.

Few farmers are making long-term commitments. Securing long-term or permanent commitments to convert hard-to-farm land to trees and grasses is the best way to build soil carbon. But as of May, the vast majority of CRP acres are enrolled through short-term contracts that allow the land to be plowed up after contracts expire, potentially releasing soil carbon back into the atmosphere.

Less than 4 million acres are enrolled through two CRP subprograms that have bigger climate benefits – CLEAR30 and the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program – which can offer farmers long-term options. And most of these acres are also enrolled through short-term contracts.

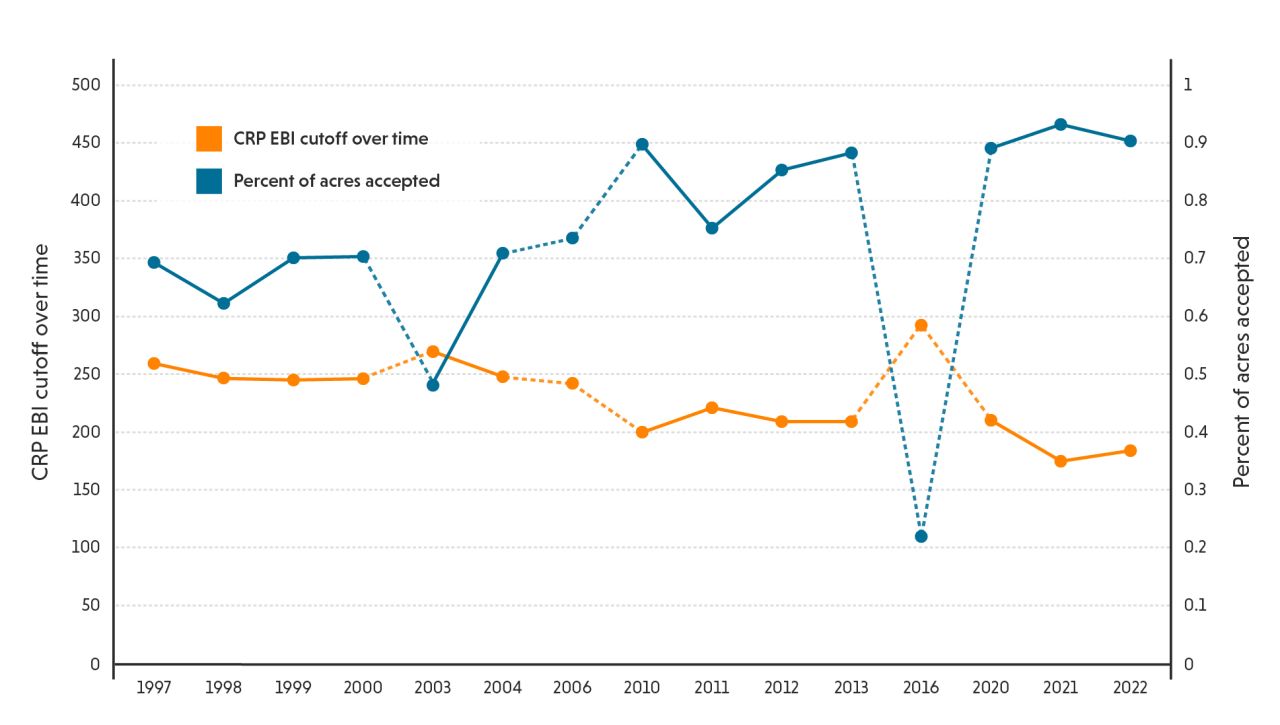

Land with fewer environmental benefits is being enrolled in the CRP. Rather than setting and maintaining a high bar for land accepted into the CRP, the USDA has gradually lowered the bar for CRP enrollment and accepted more offers. (See chart.)

In 1997, the USDA required an EBI score of 259 for land to be accepted into the CRP, and less than 70 percent of offers were accepted. In 2022, the required EBI score was 158, and more than 90 percent of offers were accepted.

A lower bar helps keep enrollment levels higher. But it also means land accepted into the CRP is producing fewer benefits for the environment.

Source: Department of Agriculture.

Incentive payments are too low to encourage enrollment by the lands with the most potential to build soil carbon. The USDA has increased incentive payments to encourage farmers to enroll lands with the potential to address the climate crisis. The USDA in 2021 provided a special incentive payment for climate-smart practices. But at a time of high crop prices, the incentive payments are still not high enough to persuade farmers to convert hard-to-farm lands to trees and grasses through long-term or permanent agreements.

Congress should modernize the CRP to combat the climate crisis. Although the USDA has adjusted the CRP, Congress has not modernized the program since it was created in 1985. While more and more farmers are choosing to create buffers and similar practices through the CRP’s “continuous enrollment” process, more needs to be done to make wise use of the CRP, which is expected to cost more than $2 billion annually in the coming years.

Congress should increase the amount the USDA pays farmers to convert hard-to-farm lands to trees and grasses and reduce the amount that takes productive farmland out of production for a short time, as Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.) proposed, and should encourage more farmers to seek long-term agreements.

.jpg?h=827069f2&itok=jxjHWjz5)